Introduction

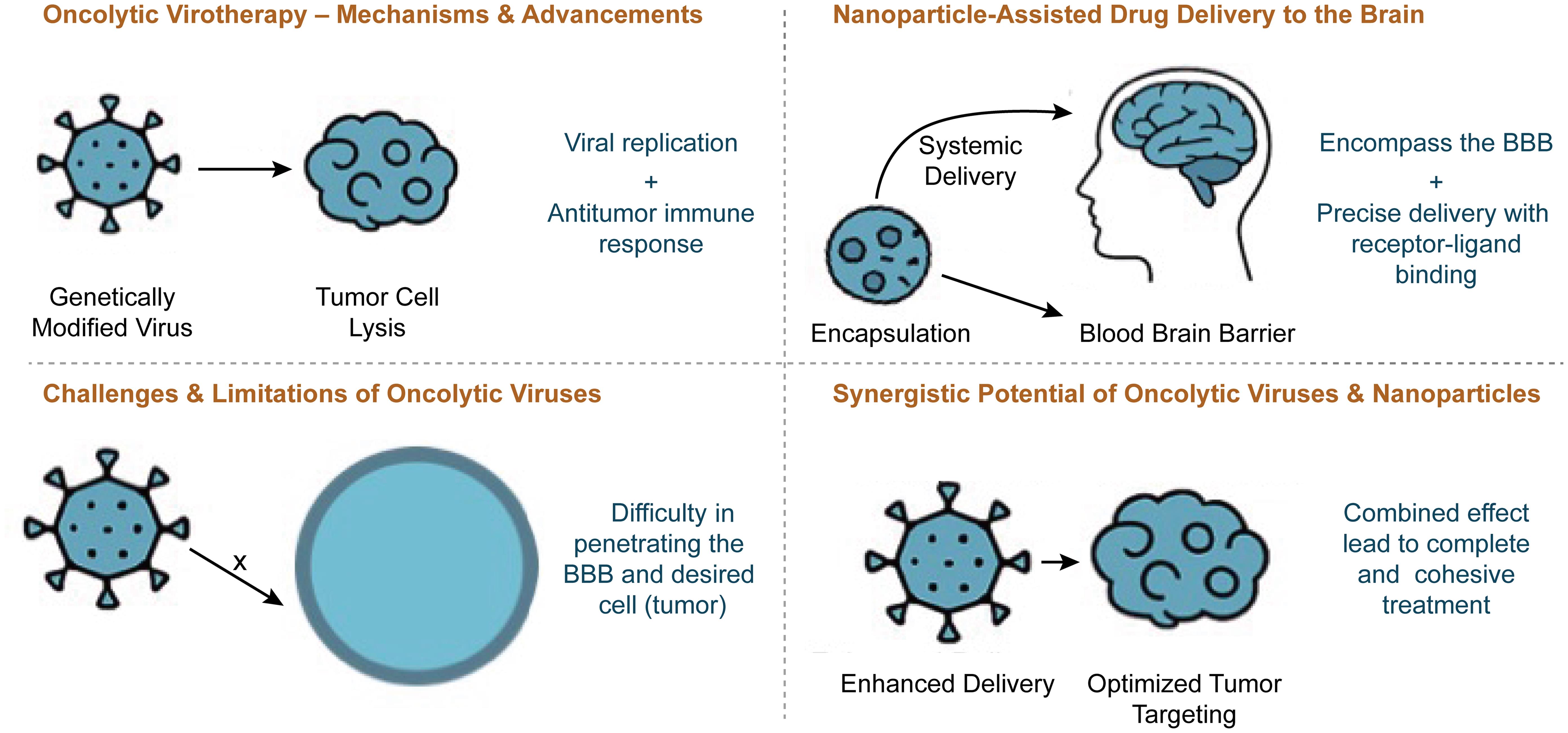

Despite advancements in brain cancer treatment, conventional therapies often face limitations such as achieving therapeutic efficacy while minimizing toxicity. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), the first and only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved oncolytic virus for melanoma, was introduced over a decade ago.1 One major challenge is ensuring precise drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) while minimizing systemic toxicity. Oncolytic viruses, genetically engineered to selectively replicate inside and destroy cancer cells, have emerged as a promising strategy in immunotherapy.2 In addition to lysing tumor cells, these viruses can stimulate an immune response, enhancing the body’s ability to recognize and attack malignancies.3 Meanwhile, nanoparticle-assisted drug delivery increases precision, improving therapeutic outcomes by optimizing drug release and targeting mechanisms.4 These strategies collectively improve drug delivery, reduce toxicity, and enhance therapeutic efficacy.5 The integration of these two approaches significantly expands the potential for precise, targeted, and immune-enhanced cancer therapy, offering a revolutionary step forward. To understand the potential synergy between these approaches, it is essential to examine their individual advancements and existing limitations.

Over the past two decades, oncolytic virotherapy has emerged as a promising approach in cancer treatment, leveraging genetically modified viruses to specifically destroy tumor cells while sparing healthy tissue.6 Studies have demonstrated the ability of oncolytic viruses, such as herpes simplex virus and adenovirus derivatives, to enhance immune activation and improve tumor regression.7 Despite these advancements, limitations remain—such as inefficient systemic delivery, immune clearance, and the challenge of crossing the BBB in glioblastoma treatment.8 To address these challenges, nanoparticle-assisted drug delivery boosts virotherapy effectiveness by improving targeted delivery and reducing immune clearance. Nanoparticles have revolutionized drug delivery in oncology by improving pharmacokinetics, enhancing drug stability, and enabling precise targeting of tumor sites.9

Although each technology has shown remarkable progress independently, research on their combined application in brain cancer treatment is still in its early stages.10 Few studies explore the synergistic effects of using herpes simplex virus-1 oncolytic viruses encapsulated in nanoparticles for enhanced delivery and therapeutic outcomes, leaving a gap in the literature that warrants further investigation.

This literature review examines current advancements in oncolytic virotherapy and nanoparticle-based drug delivery, assessing their potential synergy in enhancing drug delivery, immune response activation, and overcoming therapeutic resistance in brain cancer. By synthesizing existing research, identifying gaps, and evaluating future applications, this review provides a foundation for advancing integrative therapeutic strategies.

Methodological note

Numerous reviews and meta-analyses have been published, especially in recent years, that synthesize clinical and nonclinical data collected over the last several decades, consistent with a 25-year timeframe (e.g., from the early 2000s or 1990s to the present). The field gained significant momentum following key genetic engineering advancements around the early 1990s, making a 25-year scope highly relevant for capturing the “modern era” of oncolytic virus development.11

Examples of such reviews include:

Articles that provide a comprehensive overview of oncolytic viruses, their mechanisms, modifications, and clinical trial results, often covering research since the early 2000s.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses that specifically collect data from numerous clinical trials to compare the safety and efficacy of different oncolytic virus treatments and combination therapies over an extended period.12

This type of review provides a valuable summary of the progress from early concepts to the development and FDA approval of the first oncolytic virus therapy (T-VEC in 2015), as well as ongoing research into combination therapies.13,14

Oncolytic virotherapy

Mechanisms & advancements

Oncolytic viruses represent a revolutionary breakthrough in cancer treatment, using genetically modified viruses to selectively destroy tumor cells while simultaneously enhancing antitumor immunity through antigen release and inflammatory activation in the tumor microenvironment.15 Current research considers several viruses that naturally infect the brain, including but not limited to adenoviruses, herpes simplex viruses, varicella-zoster virus, and enteroviruses. T-VEC, the first and only FDA-approved oncolytic virus for melanoma, demonstrated the ability to selectively replicate inside tumor cells while triggering an immune response.1 Research, including studies like these, has demonstrated a substantial impact on tumors and immune activation. By modifying viral genes, scientists have enhanced tumor specificity, reduced neurovirulence, and improved the presentation of lysed cancer cells to immune cells, aiding tumor clearance.2 One study highlights how genetically engineered oncolytic viruses activate T cells, enhancing tumor regression and strengthening immune responses against malignancies.16 Despite these successes, challenges such as immune clearance and systemic delivery obstacles still exist.17 These hurdles drive researchers to explore innovative solutions, including advanced drug delivery systems such as nanoparticles, intranasal methods, and gene therapy vectors, among others.18 Despite these challenges, oncolytic virotherapy continues to be a promising cancer treatment. Incorporating nanoparticle-assisted drug delivery could enhance viral selectivity, improve BBB penetration, and optimize therapeutic outcomes.

Current preclinical findings: Preclinical research in nanotherapy continues to show promising results, though efficacy in animal models does not always equate to human outcomes.19

Targeted cancer therapies: Studies frequently demonstrate that targeted nanocarriers, such as antibody-conjugated or ligand-functionalized nanoparticles, can attenuate tumor growth and improve outcomes in murine models. These systems improve drug accumulation at the tumor site and minimize off-target effects compared to free drugs.

Immunotherapy enhancement: Nano-formulations are used as adjuvants or carriers to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapeutic agents by improving their solubility and enabling sustained, targeted release in the tumor microenvironment.

Triggered release systems: Responsive nanoparticles (e.g., pH-sensitive or redox-responsive) are being investigated in preclinical studies to release drugs “on demand” in the specific tumor microenvironment, showing effective control over drug release and reduced systemic toxicity in animal models.20

However, nanotherapy faces several challenges in translation from the laboratory to the clinic, including biological barriers, manufacturing issues, and a lack of specific regulatory guidelines. While preclinical studies show immense potential for targeted drug delivery and enhanced efficacy, clinical adoption is hampered by the complexity of biological interactions and the need for rigorous long-term safety data.21,22

Regulatory challenges: Regulatory challenges are a significant hurdle to nanotherapy commercialization and widespread clinical use.22

Lack of specific guidelines: There is generally a lack of standardized, comprehensive regulatory guidelines (from agencies such as the FDA and European Medicines Agency) tailored specifically to nanomedicine, which has physicochemical properties distinct from conventional medicines. Products are often assessed using existing frameworks for generic products, which may be inadequate.

Safety and toxicity assessment: The unique size and high surface reactivity of nanoparticles make their interactions with biological systems complex and not fully understood. Predicting long-term toxicity, immunogenicity, and biodistribution (accumulation in organs such as the liver or spleen) from preclinical studies is difficult, as animal models often do not accurately predict human immune responses.

Manufacturing and quality control: The complex nature of nanoparticles makes large-scale manufacturing difficult, leading to potential batch-to-batch inconsistencies in size, surface charge, and drug loading. Ensuring a consistent, sterile, and stable product presents major quality control challenges that regulatory bodies scrutinize heavily.

Bioequivalence issues: Demonstrating bioequivalence for follow-on or generic versions of approved nanomedicines (e.g., liposomal doxorubicin) is difficult due to the complex characterization required, necessitating extensive analytical, nonclinical, and clinical data.

Cost and accessibility: High research and development and manufacturing costs contribute to the high price of nanotherapeutics, limiting accessibility, especially in low- to middle-income countries, and raising ethical questions about equitable access to advanced therapies.23

Realistic translational pathways: Realistic translational pathways for nanotherapy focus on practical applications that leverage the unique properties of nanoparticles while carefully managing inherent challenges.24

Enhanced drug solubilization and bioavailability: Nanocarriers can significantly improve the solubility and stability of hydrophobic drugs, leading to better bioavailability and therapeutic outcomes. This is a primary, pragmatic application that has already seen clinical success (e.g., Abraxane, a nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel).

Passive targeting via the enhanced permeability and retention effect: In cancer therapy, the enhanced permeability and retention effect, whereby nanoparticles accumulate in leaky tumor vasculature, remains a primary mechanism for passive targeting. Strategies leveraging this effect, combined with imaging technologies to confirm accumulation, are a major focus of current translation efforts.

Overcoming biological barriers (e.g., BBB): Nanoparticles are being engineered with specific ligands to cross difficult biological barriers, such as the BBB. This has strong potential for treating central nervous system diseases and brain tumors, where conventional drugs often fail to reach the target site at therapeutic concentrations.

Vaccine development: Lipid nanoparticles have been highly successful in mRNA vaccines (e.g., the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines), demonstrating a clear and rapid translational pathway in the field of vaccinology and gene therapy.24

Challenges & limitations of oncolytic virotherapy

Despite significant advancements in oncolytic viruses, challenges such as immune clearance, systemic delivery inefficiencies, and therapeutic resistance continue to hinder their effectiveness and increase toxicity, limiting widespread adoption.25 Ongoing research faces additional limitations, including poor oncolytic virus penetration into tumors, short persistence, and host antiviral immune responses, all of which impede the clinical translation of oncolytic virotherapy.15 Drug delivery remains a major hurdle for oncolytic viruses, involving challenges such as biological barriers, stability and solubility issues, off-target effects, and the balance between safety and efficacy in systemic administration and absorption. In brain-specific drug delivery, therapies encounter biological barriers such as the BBB, often losing efficacy before reaching the target site. This imbalance between safety and efficacy leads to off-target effects and limited absorption.25,26 These challenges have sparked growing interest in alternative delivery methods, such as nanomedicine, to enhance targeting efficiency. A major limitation of oncolytic viruses is immune clearance, whereby the host immune system rapidly detects and eliminates viral particles before they achieve full therapeutic effect.27 Although strategies such as immune suppression or genetic modifications have been explored to delay clearance, they pose risks of adverse effects, leaving challenges unresolved. The immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment presents another obstacle to effective oncolytic virotherapy, preventing robust immune activation and limiting viral replication within tumors.8

Researchers have attempted to overcome this by integrating cytokines such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor or interleukin-12 to stimulate immune responses, yet optimizing this approach remains an obstacle. Given these challenges, integrating advanced delivery mechanisms—such as nanoparticles—into oncolytic virotherapy presents a promising strategy for improving therapeutic outcomes in brain cancer treatment.

Lack of systematic studies required for regulatory

Submissions: The FDA reviews efficacy and safety data for various drug products (small molecules, biologics, nucleic acids), medical devices, and combination products.28 As of January 20, 2020, the FDA released five guidance documents for industry to express the Agency’s view of cosmetic, veterinary, and human pharmaceutical products containing nanotechnology.29 Currently, products containing nanomaterials are regulated according to the safety and efficacy regulatory framework established for other drug products, but with some nuances. For example, if a nanotechnology product contains both small-molecule drugs and biologics, then the studies required for drugs and for biologics would both have to be undertaken to characterize that nanomaterial.28 The FDA has a series of indication- and product-specific guidance documents for gene therapies.30 However, specific guidance recommendations for nucleic acid nanoparticles (NANPs) are not yet among these documents. Bioavailability, barrier penetration, in vivo delivery, and unwanted toxicity create safety concerns that are among the major obstacles preventing the field from entering clinical stages. Studies investigating NANP absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME/Tox), as well as understanding clearance rates and safety in rodent and non-rodent species, are needed prior to clinical studies.

These barriers can be eliminated by (i) developing NANP-based formulations targeted to organs and tissues other than the liver (i.e., extrahepatic targeting of NANPs); (ii) sensing and actuation for improving the therapeutic index; (iii) performing in vivo studies in rats and dogs or non-human primates and comparing the findings with those from traditional nucleic acid therapeutics; (iv) organizing seminars and workshops between academic and industrial researchers working on RNA and DNA NANPs and regulatory scientists; and (v) promoting FDA reviewers’ interaction with, and provision of guidance to, academic investigators regarding study design for ADME/Tox and the immunological safety of drug products and vaccines.

Inefficient communication between stakeholders: The gap in communication between clinicians and nanotechnologists further delays the understanding and timely identification of important therapeutic challenges. This barrier may be reduced or eliminated by the following activities: (i) creating non-monetary incentives for clinicians to present achievable webinars on unmet needs in particular therapeutic areas; (ii) creating forums for clinicians and scientists to brainstorm ideas and discuss potential collaborations; and (iii) initiating new funding opportunities to drive these translational collaborations. In each of these cases, an overarching need for academic researchers and basic scientists involved in NANP studies is to demonstrate both clear efficacy and translational capability for the Valley of Death to be crossed. Whereas traditional funding mechanisms and academic publication rewards are well-suited to the former, they are not typically oriented toward supporting the latter. Moreover, academic researchers are not typically trained, equipped, or financially supported for translation, which will require a new, collaborative model to emerge for NANPs to translate successfully to the clinic in the near future.

Nanoparticle-assisted drug delivery in neurological disorders

Nanoparticles have revolutionized drug delivery across various regions of the body, including the brain. They offer enhanced precision, stability, and bioavailability, overcoming formidable challenges such as BBB permeability and other physiological barriers.31 Traditional drug delivery systems, such as oral administration, parenteral administration, direct injection, and intranasal delivery, pose significant risks and adverse effects. They also struggle to effectively reach target sites, particularly the brain. Advances in nanoparticle technology offer unparalleled precision by facilitating exact drug transport while minimizing systemic toxicity.32

Nanoparticles encapsulate therapeutic agents, ensuring precise drug delivery while minimizing toxicity. Their efficacy is further enhanced through receptor-ligand binding.33 A study by Abaidullah et al.4 showed that polymeric nanoparticles significantly enhanced drug penetration across the BBB in glioblastoma treatment, leading to improved therapeutic efficacy and reduced systemic adverse effects.4 Despite their potential, nanoparticles face challenges such as unpredictable immune responses, formulation complexity, and regulatory hurdles. These obstacles must be addressed through further research before widespread clinical adoption.5 While nanoparticles offer a promising solution for overcoming neurological drug delivery challenges, their integration with oncolytic virotherapy could further enhance treatment specificity, efficacy, and immune activation in brain cancer therapy.

Synergistic potential of oncolytic viruses & nanoparticles

Integrating nanoparticle-based drug delivery with oncolytic virotherapy offers a promising strategy for overcoming key therapeutic challenges faced by oncolytic viruses, enhancing precision, minimizing off-target effects, and improving tumor targeting. Nanoparticles enhance viral delivery by serving as protective carriers, shielding therapeutic agents from immune detection and premature clearance.5 Additionally, they address systemic delivery inefficiencies by ensuring precise localization through receptor-ligand binding.34 Nanoparticles are engineered to cross vascular barriers, such as the BBB, enabling systemic administration while avoiding harm to healthy cells and minimizing off-target effects.31 Encapsulation preserves drug efficacy until it reaches the intended location.35 Stability, solubility, and absorption limitations are further mitigated by nanoparticle coatings, improving drug bioavailability.36 By delivering oncolytic viruses directly to tumors while enhancing immune activation, nanoparticle-assisted virotherapy can improve primary tumor destruction and systemic immune surveillance, thereby reducing recurrence risks.37 While preliminary studies indicate improved therapeutic outcomes, research on herpes simplex virus-1-encapsulated nanoparticles remains underdeveloped, highlighting a critical gap for further investigation.38 The potential synergy between oncolytic virotherapy and nanoparticle-assisted drug delivery underscores the necessity for continued research to refine formulations, enhance clinical translation, and establish long-term efficacy in brain cancer treatment.

Table 1 is presented to summarize the oncolytic viruses that are approved or under investigation for brain cancer (specifically high-grade gliomas/glioblastoma). Note that only a few oncolytic viruses are approved anywhere in the world, and most are in clinical trials.39,40–50

Oncolytic viruses approved and under investigation for brain cancer

| Oncolytic virus | Viral backbone | Approval status (region) | Cancer target | Key features | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teserpaturev (Delytact®) | Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) | Approved (Japan, conditional) | Recurrent glioblastoma (GBM) | Triple-mutated HSV-1 (G47Δ) that replicates selectively in cancer cells | 41 |

| IMLYGIC® (talimogene laherparepvec, T-VEC) | HSV-1 | Approved (US, Europe, Australia) | Melanoma (advanced) | Not approved for brain cancer, but globally approved as oncolytic virus | 42 |

| Oncorine (H101/ONYX-015) | Adenovirus | Approved (China) | Head and neck cancer | Not approved for brain cancer, but globally approved as oncolytic virus | 43 |

| DNX-2401 (tasadenoturev) | Adenovirus (Δ24-RGD) | Under investigation (Phases I/II) | High-grade glioma (HGG), diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) | Engineered to replicate in tumor cells with dysfunctional Rb pathway | 44 |

| Poliovirus Sabin and RIPO for Rhinovirus IRES Poliovirus Open reading frame (PVS-RIPO) | Poliovirus chimera | Under investigation (Phase II) | Recurrent GBM | A non-pathogenic recombinant poliovirus variant that targets the CD155 receptor, overexpressed on GBM cells | 45 |

| G207 | HSV-1 | Under investigation (Phases I/II) | Recurrent malignant glioma, cerebellar tumors | A second-generation HSV that has shown safety and radiographic responses, particularly in combination with radiation | 46 |

| CAN-3110 (rQNestin34.5v.2) | Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) | Under investigation (Phase I) | Recurrent high-grade glioma | Received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Fast Track designation. Its effectiveness is linked to nestin expression in cancer cells | 47 |

| Reolysin (pelareorep) | Reovirus | Under investigation (Phase I) | Malignant glioma, brain metastasis | A wild-type reovirus that selectively targets tumor cells with an activated Ras pathway | 48 |

| Toca 511 (vocimagene amiretrorepvec) | Retrovirus | Under investigation (Phases I/II) | Recurrent high-grade glioma | Engineered to convert the prodrug 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC) into the potent chemotherapy 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) locally in the tumor | 49 |

| H-1 parvovirus | Parvovirus (rodent origin) | Under investigation (Phases I/IIa) | Recurrent GBM | No pre-existing immunity in humans, which is a potential advantage | 50 |

Research gaps & future directions

Although integrating oncolytic virotherapy with nanoparticle-assisted drug delivery presents a promising strategy for brain cancer treatment, several research gaps must be addressed to optimize efficacy, safety, and clinical scalability, as emerging challenges persist. Tumor evolution may lead to drug resistance, but the aggressively replicative nature of viruses offers a potential mechanism for controlling tumor growth, not only in fragile regions like the brain but also in other affected areas. Other limitations of this review involve low single-agent efficacy, difficulty in predicting patient response, the need for GMP production, and determining the optimal timing for combination therapies.51

Future studies should focus on suppressing the immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment, improving drug bioavailability, and addressing therapeutic resistance. Experimentation with cytokines and genetic modifications may enhance safety and efficacy while minimizing toxicity. Successful clinical translation of nanoparticle-assisted virotherapy requires rigorous preclinical testing to evaluate biocompatibility, immune interactions, and regulatory approval.52 Advancements in nanoparticle engineering and synthetic virology hold the potential to refine brain cancer treatments, paving the way for precise, scalable, and effective therapeutic interventions. Addressing these critical gaps will unlock new opportunities for highly targeted, immune-enhanced cancer therapies, driving a transformative shift in oncology.

The integration of oncolytic virotherapy and nanoparticle-assisted drug delivery presents a groundbreaking approach to brain cancer treatment, offering enhanced tumor specificity, improved immune activation, and greater therapeutic precision (Fig. 1).

While both technologies have demonstrated significant advancements independently, their combined application remains underexplored, leaving a critical gap in current research. Future research must address this gap by refining viral selectivity, strengthening immune response activation, and ensuring precise drug delivery through nanoparticle encapsulation. Although this approach is promising, further studies on formulation optimization, immune interactions, and large-scale clinical translation are essential to refine and validate its efficacy. Since several molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance characterize glioblastoma, developing dynamically targeted nanoparticles to surface cell markers, signaling pathways, and the tumor microenvironment poses an exciting and demanding possibility.

Solid lipid nanoparticles have emerged as a promising vehicle for delivering therapeutic agents across the BBB, offering a range of advantages such as controlled drug release, extended circulation within the bloodstream, precise targeting, and reduced potential for toxicity. Notably, researchers have made significant strides in this field, with the development of lipid-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles modified with Angiopep-2 for treating gliomas.

Another point that should be considered is the difference between systemic and intratumoral delivery in central nervous system cancers. Systemic delivery involves administering drugs intravenously to reach the entire body, including the brain, but is limited by the BBB, which restricts the passage of most drugs. Intratumoral delivery directly injects drugs into the tumor, bypassing the BBB to achieve higher concentrations at the tumor site and reducing systemic adverse effects. Intratumoral delivery is often more effective for brain tumors because it increases local drug concentration and can be less toxic to healthy tissues. There are, however, additional comparative advantages over other emerging combinatorial modalities (e.g., nanoparticle-assisted immunotherapy or gene therapy). Compared with other combinatorial modalities, such as nanoparticle-assisted immunotherapy or gene therapy alone, a major advantage is the ability to achieve synergistic effects by combining delivery precision with a therapeutic mechanism. For instance, nano-immunotherapy can overcome the limitations of each individual approach by using nanoparticles to deliver immunotherapies more precisely, thereby increasing their effectiveness against tumors and potentially correcting genetic defects. Therefore, it appears that integrating virotherapy with precision drug delivery marks a significant innovation that could redefine cancer treatment strategies and enhance patient outcomes globally.

Conclusions

This review is an excerpt from scientific publications that discusses the challenges and potential benefits that may be obtained from combining nanomedicine and viral therapy in neuro-oncology. While we have highlighted the progress that has been made in this area, clinical application is still limited due to many key challenges, like Delivery inefficiencies, Immune clearance, and Safety concerns. Overall, it concludes by emphasizing the need for further research with combinational approach to redefine the treatment paradigms and improve the prognosis of brain cancer.

Declarations

Acknowledgement

Both authors are sincerely grateful to Dr. Anil Diwan and Mr. Yogesh Thakur for their invaluable guidance and feedback throughout this review.

Funding

No funding was received.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Ashok Chakraborty is a Sr. Research Scientist at Allexcel, Inc. The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this article. The authors also confirm that they have read the journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Chemistry or the University.

Authors’ contributions

Information search and writing of the manuscript (AC, MY). Both authors have approved the final version and agreed to submit to the Nature Cell and Science journal for publication of this article.

Author information

Author information