Introduction

Retinal laser photocoagulation has been a cornerstone of ophthalmic therapeutics for decades. Since its introduction in the 1960s, conventional thermal laser has revolutionized the management of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and various macular pathologies.1,2 However, the therapeutic benefits of standard photocoagulation come at the cost of collateral retinal damage. The generation of visible burns is associated with disruption of photoreceptor architecture, permanent scarring, paracentral scotomas, and, in some cases, progressive enlargement of laser scars.3 These limitations have motivated the search for alternative therapeutic modalities that can provide comparable efficacy while minimizing tissue damage.

Subthreshold laser therapy emerged from this context as a refinement of traditional laser approaches. Instead of deliberately creating a visible burn, subthreshold techniques aim to stimulate biological responses in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) without inducing thermal necrosis.4,5 The absence of ophthalmoscopically detectable endpoints renders the procedure titration dependent; however, it also confers a substantial safety advantage by avoiding overt retinal injury.6 Over the past two decades, technological innovations such as micropulse lasers, nanosecond pulses, and pattern-scanning delivery systems have expanded the range of subthreshold strategies, making them increasingly relevant for macular diseases.7

The clinical use of subthreshold laser therapy has been investigated in diabetic macular edema (DME), central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR), age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and other conditions in which RPE dysfunction and choroidal abnormalities play pivotal roles.8–11 Although anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections and photodynamic therapy (PDT) remain the mainstay treatments for many of these diseases, subthreshold laser provides a minimally invasive, repeatable, and cost-effective option that is particularly attractive in resource-limited settings or for patients requiring long-term therapy.12

This narrative review synthesizes current knowledge on macular subthreshold laser therapy, focusing on its principles, mechanisms, clinical applications, outcomes, and practical limitations.

Principles and mechanisms of subthreshold laser therapy

The concept of “subthreshold” laser therapy is defined by its ability to deliver energy below the level that produces a visible retinal burn. Whereas conventional photocoagulation relies on a clinically detectable whitening of the retina as evidence of tissue coagulation, subthreshold therapy avoids this destructive endpoint. Instead, the therapeutic goal is to induce controlled RPE activation, stimulating repair pathways and restoring retinal homeostasis without causing structural damage to the neurosensory retina.13,14

Several techniques have been developed to achieve this effect. The most widely used is subthreshold micropulse laser (SML), in which energy is delivered in very short pulses separated by “off” intervals, allowing heat to dissipate between exposures. This duty cycle prevents cumulative tissue necrosis while still stimulating the RPE. Micropulse systems are available in different wavelengths, most commonly 577 nm (yellow) and 810 nm (infrared). Other approaches include reducing the continuous-wave laser power to below the burn threshold and using nanosecond pulses that minimize heat diffusion. These innovations share the goal of maximizing therapeutic stimulation while preserving tissue integrity.5

The biological effects of subthreshold therapy are thought to occur at the cellular and molecular level within the RPE. Sublethal thermal stress leads to upregulation of protective heat shock proteins, improved resistance to oxidative stress, and stabilization of protein folding. Laser stimulation also influences cytokine and growth factor expression, promoting a shift toward anti-angiogenic and anti-permeability profiles, with downregulation of VEGF and upregulation of pigment epithelium–derived factor. RPE pump function and tight junction integrity are enhanced, facilitating fluid resorption from both the subretinal and intraretinal spaces. Preclinical studies also suggest a degree of neuroprotection for photoreceptors by reducing inflammatory cascades and oxidative damage.15,16

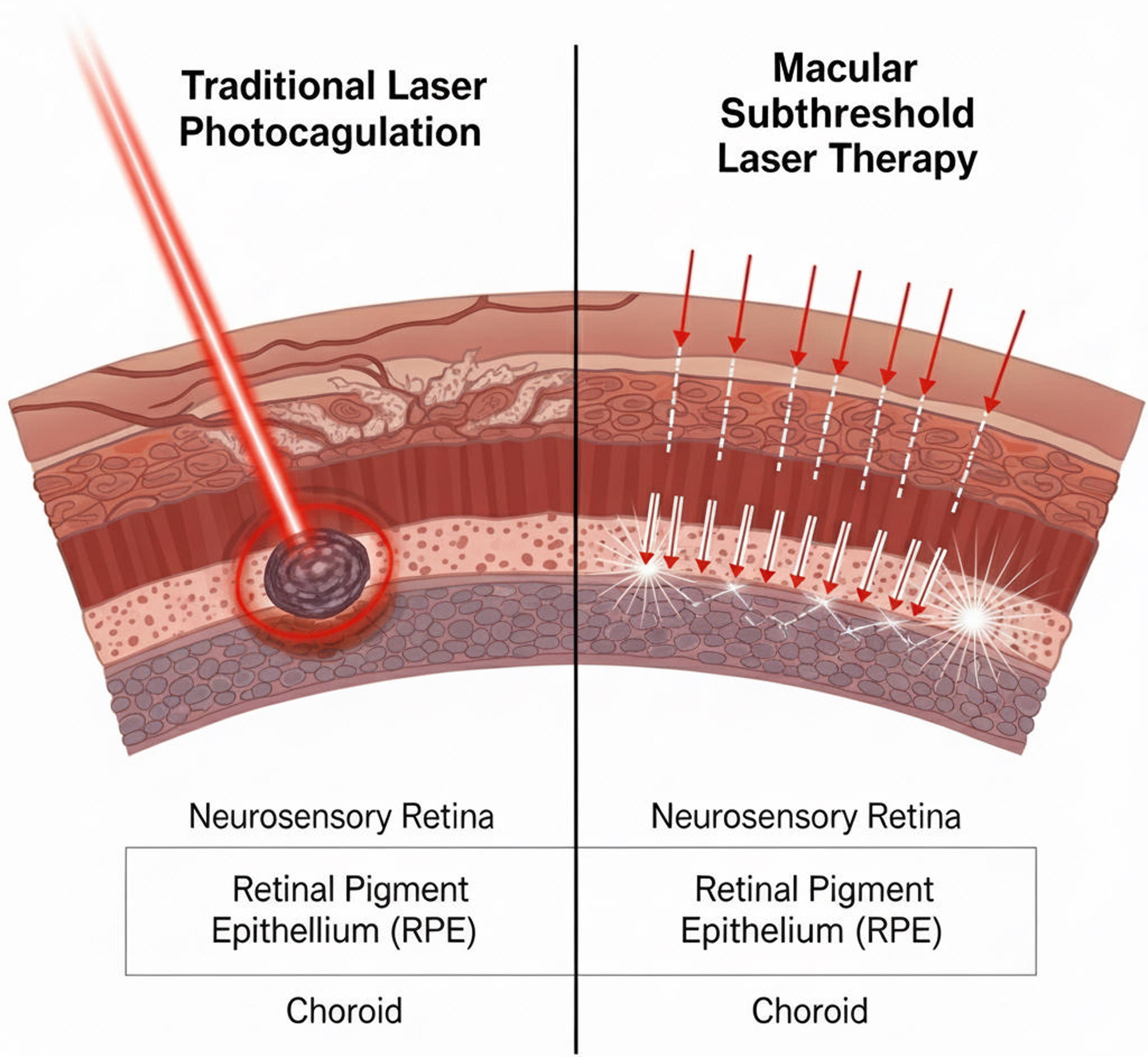

Unlike conventional burns, the effects of subthreshold treatment are not visible on ophthalmoscopy or fluorescein angiography. Subtle changes may be detectable with more advanced imaging, such as fundus autofluorescence or optical coherence tomography (OCT), but the lack of scarring remains its defining feature (Fig. 1). This invisibility is a double-edged sword: it confers safety and repeatability but requires careful titration of parameters and reliance on indirect measures to judge the adequacy of treatment (Table 1). Ultimately, subthreshold laser represents a shift from destructive tissue ablation toward functional modulation of the RPE and its microenvironment.17

This schematic illustration contrasts the tissue effects, treatment endpoints, and functional outcomes of conventional continuous-wave retinal photocoagulation versus SML. Traditional photocoagulation produces visible retinal whitening due to thermal coagulation of the neurosensory retina and RPE, leading to permanent scars, photoreceptor loss, and potential visual field defects. In contrast, SML delivers energy in short microsecond pulses separated by “off” cycles, allowing tissue to cool between pulses and preventing thermal necrosis. As a result, SML does not generate ophthalmoscopically visible burns or structural damage on OCT, fundus autofluorescence, or fluorescein angiography. Instead, it induces sublethal RPE biomodulation, enhancing fluid transport and reducing inflammation, with preservation of photoreceptors and retinal sensitivity. The figure highlights the safety advantages and non-destructive nature of SML compared with conventional lasers. OCT, optical coherence tomography; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; SML, subthreshold micropulse laser.

Key differences between subthreshold laser and traditional laser photocoagulation

| Feature | Subthreshold laser | Traditional laser photocoagulation |

|---|---|---|

| Visible damage | None; no scarring | Creates a visible white burn and a permanent scar |

| Mechanism | Stimulates cellular repair and function (retinal pigment epithelium) | Destroys tissue to reduce oxygen demand and leakage |

| Complications | Very low risk; avoids adverse effects of scarring | Risk of visual field loss, reduced contrast sensitivity, epiretinal fibrosis, and potential for choroidal neovascularization |

| Treatable area | It can be safely applied in and around the foveal avascular zone (the center of the macula) | Avoided in the central fovea due to the risk of vision loss from scarring |

| Retreatment | Can be repeated | It cannot be repeated on the same spot due to scarring |

Clinical applications and evidence

DME

DME is one of the most studied indications for subthreshold therapy. The pathophysiology involves breakdown of the blood–retinal barrier and accumulation of intraretinal fluid. While the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study established conventional laser as a standard, anti-VEGF therapy has since become first-line. Nevertheless, laser remains relevant, particularly in patients who require adjunctive treatment or in whom the injection burden is high.18

Randomized clinical trials and systematic reviews, including Cochrane analyses, have consistently shown that SML is non-inferior to conventional laser for stabilizing vision, with superior safety.19 The DIAMONDS trial confirmed these findings in a multicenter setting, reporting equivalent visual outcomes but with no visible scarring or scotomas.20–22 A more detailed review of the major clinical trials further contextualizes the evidence supporting subthreshold laser therapy. The DIAMONDS study, a multicenter, randomized, double-masked non-inferiority trial, enrolled 266 eyes from 266 adults with center-involving DME. Participants were randomized to receive either SML or standard threshold laser and followed for 24 months. The primary endpoint was the mean change in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at 24 months. The study demonstrated that SML was non-inferior to conventional laser in terms of BCVA outcomes, with the added advantage of no visible retinal scarring and a highly favorable safety profile.22 OCT consistently demonstrates reduction in central retinal thickness after treatment, though functional improvements are often modest.19,23

Importantly, SML is safe for use near the fovea, making it advantageous in center-involving DME. When combined with anti-VEGF therapy, studies show a significant reduction in the number of injections needed to achieve similar visual outcomes, an effect particularly valuable in chronic disease and resource-constrained environments.19

CSCR

CSCR is another major indication in which subthreshold therapy has reshaped clinical management. The disease arises from choroidal hyperpermeability and RPE dysfunction, leading to subretinal fluid (SRF) accumulation. Although acute cases often resolve spontaneously, chronic or recurrent CSCR requires intervention.24,25

Conventional thermal laser has been largely abandoned due to the risks of scotomas and choroidal neovascularization (CNV). PDT became the gold standard, but it is expensive, requires verteporfin, and is not universally available. Subthreshold yellow micropulse laser has emerged as a practical alternative. Prospective and randomized studies show that it accelerates fluid resolution and improves BCVA compared to observation, with outcomes approaching those of PDT in many cases.10

Meta-analyses suggest that PDT remains slightly superior in preventing recurrences, but subthreshold therapy offers comparable functional outcomes with lower cost and fewer risks. Long-term follow-up confirms that treatment does not induce chorioretinal scarring and can be safely repeated, even when applied to subfoveal areas. Consequently, SML is increasingly recommended as first-line therapy for chronic CSCR, with PDT reserved for refractory disease.26,27

Although SML has become a widely used option for chronic CSCR, its reported efficacy varies considerably across studies. Rates of complete SRF resolution have ranged widely, reflecting differences in laser parameters, wavelengths, titration methods, disease chronicity, and imaging-defined endpoints across clinical trials. Several prospective and retrospective series have demonstrated meaningful SRF reduction and improvement in visual acuity, whereas others have reported modest or delayed anatomical responses compared with PDT.4,28 This variability underscores the lack of standardization in micropulse treatment protocols and highlights the importance of patient selection and careful titration when interpreting outcomes.

Recent evidence has further expanded the potential indications of SML to include CSCR complicated by CNV. A randomized study evaluating microsecond pulsing laser therapy in neovascular CSCR demonstrated promising results.29 In this trial, 23 eyes with OCTA-confirmed CNV received navigated microsecond pulsing laser therapy, while 12 eyes underwent sham treatment. After six months, 60.9% of treated eyes achieved complete SRF resolution and an additional 21.7% showed partial improvement, compared with 0% in the control group. Importantly, treatment did not induce CNV enlargement, increased exudation, or visual deterioration. These findings suggest that microsecond pulsed laser may represent a safe, non-invasive alternative for managing CSCR with relatively small CNV, particularly in situations in which anti-VEGF therapy is undesirable or unavailable.

AMD

The application of subthreshold laser in AMD remains investigational. Early pilot studies with nanosecond 2RT lasers demonstrated drusen regression and favorable safety profiles. However, large-scale trials have yielded mixed results. It is important to distinguish true subthreshold laser modalities from other laser strategies that may spare the central macula but still rely on intentional RPE damage. For example, the TR2 approach applies laser pulses to extramacular regions with the explicit purpose of inducing selective RPE injury. Although the foveal center is avoided, the mechanism remains fundamentally different from non-damaging subthreshold techniques, which operate below the threshold of visible or histologic retinal injury. Because subthreshold laser therapy is defined by the absence of tissue destruction and the modulation—rather than ablation—of RPE cellular responses, treatments such as TR2 do not fall within this category. The LEAD study—the largest randomized controlled trial evaluating nanosecond subthreshold laser in early AMD—randomized 292 participants with bilateral intermediate AMD to nanosecond 2RT laser or sham treatment. Subjects were followed for 36 months, with the primary endpoint being the time to progression to late AMD (geographic atrophy or neovascularization). While the overall cohort did not show a reduction in progression risk, a prespecified subgroup without reticular pseudodrusen demonstrated a significant 44% reduction in progression compared with sham. These findings highlight the importance of phenotype-based patient selection when considering subthreshold modalities for AMD.13,30,31

At present, subthreshold laser is not incorporated into AMD management guidelines, but the biological rationale remains strong. The potential to modulate RPE function and slow progression of early disease continues to drive research, particularly with more refined protocols and patient stratification.

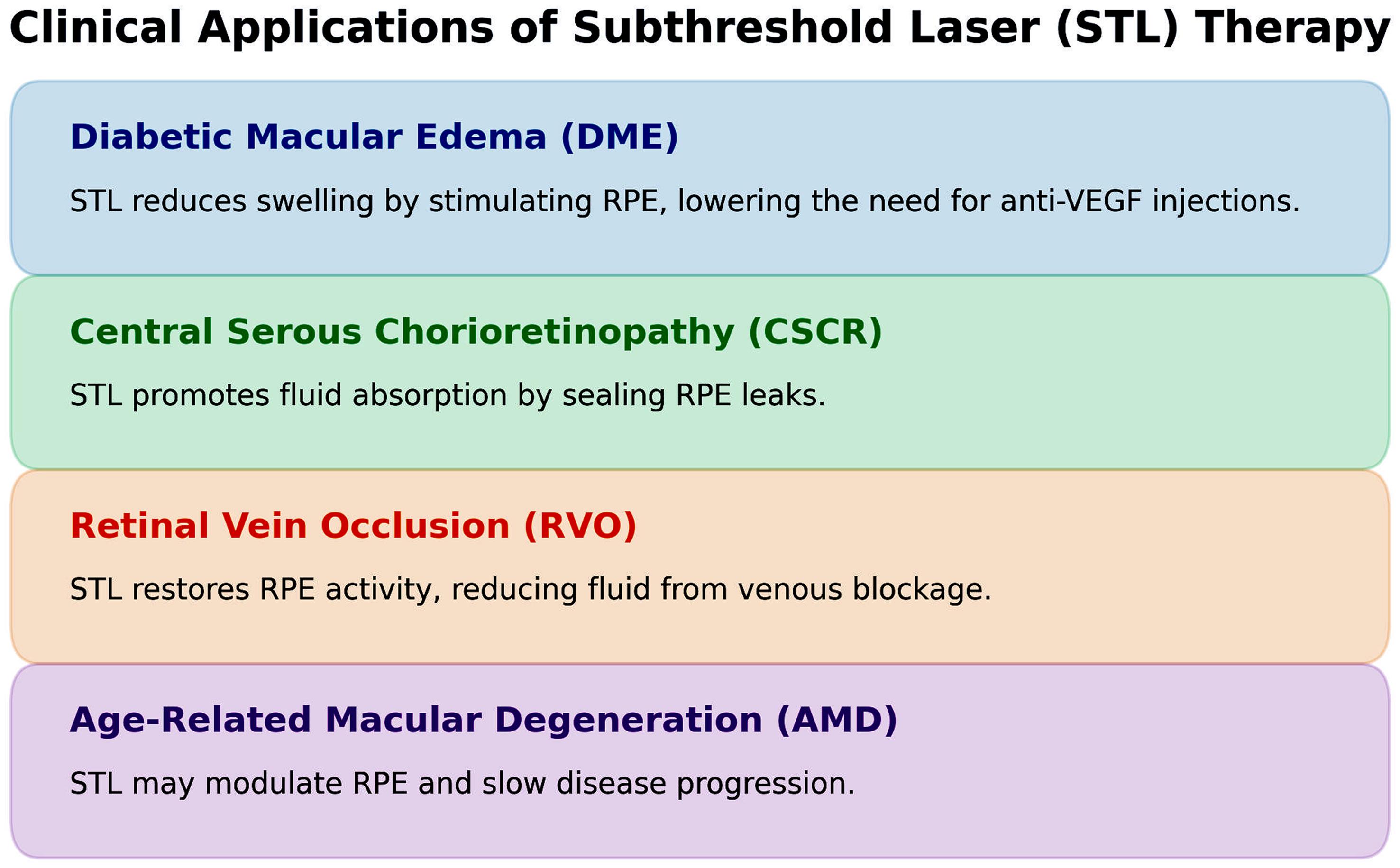

Figure 2 summarizes the major clinical conditions with acceptable response to subthreshold laser therapy.

This diagram summarizes the primary disease indications in which STL has demonstrated therapeutic benefit. The conditions shown include DME, CSCR, and selected early or intermediate forms of AMD, as well as smaller studies involving retinal vein occlusion and myopic choroidal neovascularization. The figure illustrates the central role of RPE biomodulation—rather than retinal tissue destruction—as the unifying mechanism across these disorders. Arrows indicate the direction of clinical benefit, such as reduction of subretinal or intraretinal fluid, stabilization of best-corrected visual acuity, and decreased need for intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy in combination protocols. The graphic emphasizes STL’s repeatability, safety in foveal treatment zones, and suitability for chronic or recurrent disease. AMD, age-related macular degeneration; CSCR, central serous chorioretinopathy; DME, diabetic macular edema; STL, subthreshold laser therapy; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Other indications

SMLs are available in several wavelengths, with 577-nm yellow and 810-nm infrared being the most widely used. The choice of wavelength influences tissue absorption, clinical indications, and practical workflow. The 577-nm yellow wavelength exhibits high absorption by oxygenated hemoglobin and moderate absorption by melanin, allowing efficient energy delivery to the RPE with minimal scatter and excellent precision. Its reduced xanthophyll absorption makes it inherently safe for foveal applications, and its high photothermal efficiency permits the use of lower power levels. These characteristics have led to the broad adoption of 577-nm micropulse systems in DME and chronic CSCR, in which controlled RPE modulation in or near the fovea is essential.14

In contrast, the 810-nm infrared wavelength is absorbed predominantly by melanin, with less interaction with hemoglobin. This deeper penetration and broader absorption profile historically made 810-nm systems suitable for treating thicker or more pigmented retinas. Early micropulse applications—including the original seminal studies—were performed using 810-nm infrared lasers. Clinically, 810-nm micropulse remains effective for DME and selected cases of macular edema secondary to retinal vascular disease, although retinal penetration is greater and the lateral spread of heat is wider compared with 577-nm. Infrared systems often require higher power settings and more conservative titration due to their deeper tissue interaction, but they maintain an excellent safety profile when used in true subthreshold mode.16

Several smaller studies have explored subthreshold laser in additional conditions. In retinal vein occlusion, modest improvements in edema have been reported, though anti-VEGF therapy remains clearly superior.32 Experimental applications include myopic CNV and macular telangiectasia, though these remain investigational.33

Safety profile

Across all indications, safety has been the defining strength of subthreshold therapy. Unlike conventional photocoagulation, it does not induce visible burns or scarring. Imaging and functional tests confirm preserved photoreceptor integrity and retinal sensitivity in treated areas. Multifocal electroretinography, microperimetry, and adaptive optics imaging consistently demonstrate the absence of functional damage.34

The safety profile of subthreshold laser therapy remains one of its most significant advantages, especially in CSCR, where treatment is often applied near the foveal center. A large retrospective study evaluating navigated microsecond pulsing laser in 101 eyes with chronic CSCR reported no laser-induced adverse events across a broad range of fluence settings and parameter sets,35 provided cautious titration was used. Over a mean follow-up of 10 months, none of the eyes demonstrated signs of tissue damage, RPE disruption, or inadvertent threshold burns. Clinically, 88% of cases remained stable or improved, with a mean BCVA gain of 0.07 logMAR, and 51% of eyes exhibited a significant reduction in central retinal thickness.

Perhaps most importantly, treatments can be repeated over time without cumulative harm. This makes subthreshold therapy uniquely suited for chronic or recurrent conditions. Adverse events are rare, with the most common being accidental overtreatment if parameters are set incorrectly, but even in these cases, the damage is far less severe than with threshold burns.16

Advantages and limitations

Advantages

Subthreshold laser is tissue sparing, safe for foveal treatment, and repeatable without risk of cumulative retinal injury. It preserves retinal sensitivity, is cost-effective compared with PDT and chronic anti-VEGF therapy, and is well tolerated by patients. In combination regimens, it reduces injection burden, an increasingly important advantage in the context of healthcare costs and patient adherence.6

Limitations

The absence of a visible endpoint creates challenges for standardization and titration. Different studies employ diverse protocols with variable wavelengths, duty cycles, and parameters, making cross-comparison difficult. Clinical responses are often slower and less dramatic than those of anti-VEGF therapy, which limits its use in advanced disease or in situations where rapid resolution is required. Its role in AMD and other indications remains uncertain, with evidence still inconclusive. Dependence on imaging for monitoring adds to the complexity of follow-up, particularly in resource-limited settings.6,36

Despite the challenges inherent to the absence of visible endpoints and variability across treatment protocols, several emerging technologies aim to improve reproducibility and enhance safety in subthreshold laser therapy. One promising development is the use of real-time energy titration systems, which integrate feedback algorithms to estimate localized tissue heating during micropulse emission. These platforms provide dynamic adjustment of power output to maintain sublethal thermal thresholds, thereby reducing the likelihood of overtreatment. In parallel, OCT-based individualized parameter calculations are being explored to tailor laser power, duration, and density based on the patient’s retinal thickness, RPE reflectivity, and choroidal characteristics. Early studies suggest that personalized, imaging-derived treatment maps may improve both anatomical outcomes and treatment consistency. In addition, next-generation nanosecond pulse laser systems, such as refined iterations of the 2RT technology, aim to deliver highly confined, non-thermal mechanical stimulation to the RPE while virtually eliminating collateral heat diffusion. These systems offer improved precision and may overcome some of the variability associated with micropulse duty cycles and titration procedures. Although still investigational, such advances represent important steps toward standardizing subthreshold laser delivery, improving inter-operator consistency, and potentially expanding the indications for non-damaging retinal therapy.4,37

Conclusions

Looking forward, the evolution of subthreshold laser therapy will increasingly depend on advancing our ability to deliver personalized, biologically precise treatment. Future research should prioritize the identification of imaging and functional biomarkers—such as choroidal hyperpermeability patterns, RPE dysfunction signatures, or OCT-derived structural metrics—that can help clinicians select patients most likely to benefit from subthreshold approaches. Equally important is the refinement and standardization of treatment parameters, including real-time titration, objective energy-delivery monitoring, and individualized dosing models based on retinal thickness and tissue absorption properties. As the therapeutic landscape for macular disease continues to rely heavily on anti-VEGF agents and PDT, subthreshold laser holds promise as part of combination or sequential treatment strategies, potentially reducing injection burden while enhancing long-term disease control. Further prospective, multicenter trials incorporating standardized protocols will be crucial to defining optimal patient selection, parameter configuration, and multimodal therapeutic sequencing. Ultimately, the success of subthreshold laser therapy will hinge on aligning technological innovation with mechanistic understanding to achieve consistent, durable, and clinically meaningful outcomes.

Declarations

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Authors’ contributions

MMS is the sole author of the manuscript.

Author information

Author information