Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) arises after exposure to life-threatening trauma and is characterized by intrusive memories, emotional numbing, hyperarousal, and cognitive impairments. Neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies consistently reveal hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the amygdala—particularly its basolateral amygdala and central nuclei—with hippocampal and prefrontal structures.1,2 Traditionally, such patterns were attributed to stress hormone cascades or structural degeneration; however, accumulating evidence places microglial cells at the center of circuit-level dysfunction.3–5 Microglia not only respond to injury but actively sculpt neural circuits through synaptic pruning.6–8 When this tightly regulated process is disrupted, either by inflammation, genetic predispositions, or trauma, the result can be excessive retention of excitatory synapses, leading to maladaptive connectivity.9–11 In PTSD, this mechanism may underlie persistent fear learning, impaired extinction, and poor cognitive flexibility.12–14 Major mechanisms of microglial pruning in health and trauma may include the following: complement signaling and synaptic tagging,7,15 triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2-apolipoprotein E (TREM2–APOE) and lipid sensing,9,10,11,16,17 or neuroinflammatory modulation.3,4,18,19 On the other hand, therapeutic opportunities and circuit rescue strategies include modulating microglial function (TREM2 agonists & complement inhibitors),7,10 targeting inflammation and pruning balance (minocycline & ketamine),18,20 and circuit-specific approaches.5

While microglia have long been viewed as passive immune sentinels, recent work, particularly since 2019, has redefined them as active sculptors of neural circuits through complement- and TREM2-dependent synaptic pruning.7–11,17 This conceptual shift emerged largely from Alzheimer’s disease models, where dysregulated pruning was linked to circuit failure.11,16 However, whether these mechanisms extend to stress-related psychiatric disorders like PTSD remains less explored.4,5,18 To address this, we conducted a systematic review (2019–2025) focused on studies bridging neuroimmune signaling and circuit dysfunction in PTSD.4,5,18 Although causal evidence primarily derives from preclinical models, converging human data, from postmortem tissue, neuroimaging, and inflammatory biomarkers, support the translational relevance of these pathways.1,2,12 Critically, no fundamental divergence in pruning mechanisms has been reported between PTSD of psychological versus post-viral etiology, suggesting a final common pathway of microglial dysregulation.4,5,18

The present study aimed to conduct a systematic review (2019–2025) of neuroimmune-circuit interactions in PTSD, synthesize mechanistic evidence for microglial pruning dysfunction across etiologies, and translate these findings into the design of a clinical trial targeting pruning homeostasis in post-COVID PTSD.4,5,18

Materials and Methods

Systematic review

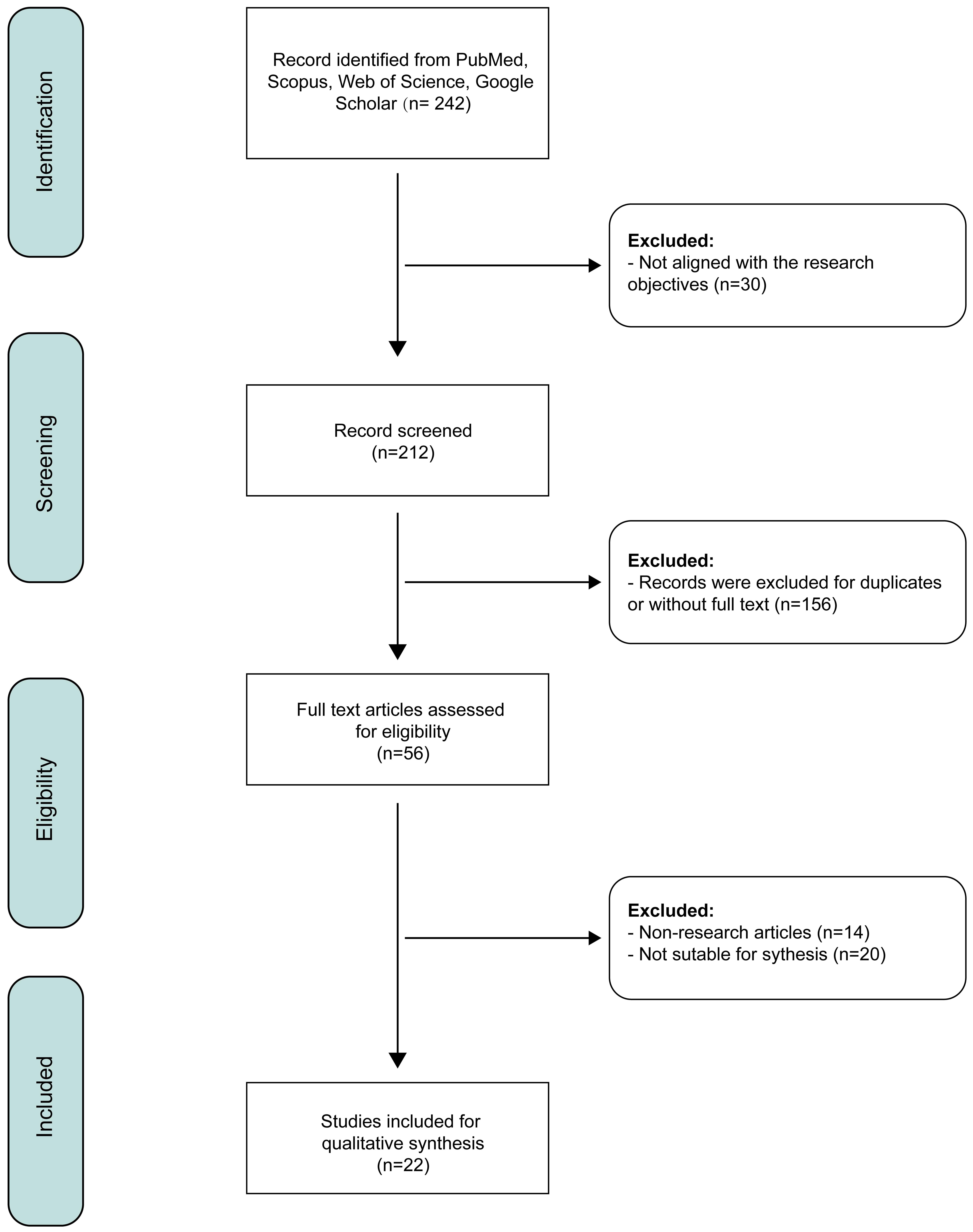

This systematic review synthesizes evidence on microglial synaptic pruning and its role in amygdala hyperconnectivity in PTSD, following PRISMA guidelines (Fig. 1).8 A comprehensive literature search was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar using predefined keywords, including “microglial synaptic pruning,” “amygdala hyperconnectivity,” “TREM2-APOE pathway,” “complement signaling,” and “neuroinflammation in PTSD”.7 Studies published between January 2019 and June 2025 were included, with a focus on peer-reviewed original research and reviews in English.2

A total of 249 records were identified through database searching (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar). After removing duplicates and initial screening, 212 records were screened, of which 156 were excluded. The full texts of the remaining 56 articles were assessed for eligibility; 14 were excluded (primarily due to being non-research articles), leaving 42 studies included in the qualitative synthesis.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

Relevant studies were identified through title and abstract screening by two independent reviewers (A and B), followed by full-text evaluation. Inclusion criteria prioritized preclinical models (e.g., rodent PTSD or stress paradigms), human clinical studies, and in vitro experiments investigating microglial pruning mechanisms in PTSD-related circuit dysfunction.3,12,18 Exclusion criteria eliminated non-scientific articles (e.g., editorials), studies without full-text access, and those focusing solely on hormonal or structural aspects of PTSD without addressing microglial involvement.19

Data extraction and quality assessment

Key data extracted from selected studies included author names, publication year, study models (e.g., mouse, rat, human-derived microglia), interventions (e.g., TREM2 agonists, complement inhibitors), and findings related to synaptic pruning, amygdala connectivity, or PTSD-like behaviors.7,9–11 Methodological quality was assessed using Cochrane Collaboration tools for animal studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for clinical trials. Discrepancies in data extraction or quality ratings were resolved through consensus or third-party adjudication.11

Synthesis and thematic analysis

Findings were synthesized thematically, focusing on three core mechanisms:

Complement signaling: Regional imbalances in C1q/C3-CR3 pathways (e.g., hippocampal over-pruning vs. amygdala under-pruning) were analyzed to explain PTSD-associated memory deficits and hyperconnectivity.7,15

TREM2-APOE pathways: The role of lipid sensing and phagocytic dysfunction in stress-induced synaptic overload was evaluated, with emphasis on genetic variants (e.g., APOE4) and therapeutic modulation (e.g., ketamine, TREM2 agonists).9–11,17

Neuroinflammatory modulation: Effects of cytokines (interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α) and glucocorticoids on microglial motility and pruning efficiency were assessed, alongside anti-inflammatory interventions (e.g., minocycline, Centella asiatica extract).18,19

Table 1 and Figure 2 were developed to summarize regional pruning imbalances, therapeutic strategies, and clinical trial outcomes.

Systematic review (2019–2025) on mechanisms of microglial pruning in health and trauma

| Authors | Therapeutic agent/Approach | Mechanism of action/Application | Effect on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD-like) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modulating Microglial Function | |||

| Long et al., 202410 | Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) agonists | Enhance phagocytic response; normalize disease-associated microglia (DAM) phenotype | Restore pruning; reduce fear behaviors |

| Scott-Hewitt et al., 20207 | Anti-C3 antibodies | Block excessive complement activation | Balance regional pruning, preserve circuit integrity |

| Circuit-Specific Approaches | |||

| Liu et al., 202511 | Region- and cell-specific modulation of microglia | Reversible pruning enhancement or inhibition | Enables targeted pruning repair in PTSD circuits |

| Valenza et al., 202420 | Real-time visualization of pruning | Maps regional microglial dysfunction | Biomarker development for PTSD diagnosis |

| Bourel et al., 202115 | Non-invasive measurement of pruning | Detects pruning imbalance in trauma-exposed individuals | Allows personalized therapeutic monitoring |

↑, increase; ↓, decrease. DAM, disease-associated microglia; KO, knockout.

Clinical trial

Study design and CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) compliance

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial was conducted and reported in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 guidelines. The CONSORT checklist is provided as Supplementary Material. The trial was prospectively registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT ID: IRCT20080901001165N63; registration date: October 22, 2020) and approved by the Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (protocol number: IR.BMSU.REC.1399.159). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2024) and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment after receiving a complete explanation of the study procedures and potential risks.

Participants and eligibility criteria

We investigated the efficacy of intranasal Myrtus communis extract (MCE) (Netus® nasal spray, manufactured under good manufacturing practice conditions by Ismail Qaderi Pharmaceutical Company, Hamadan, Iran) in post-COVID-19 patients exhibiting persistent cognitive impairment and anxiety symptoms. Participants (n = 60; mean age 45 ± 12 years; 32 females) were recruited from the Post-COVID Clinic at Baqiyatallah Hospital between November 2020 and March 2021 based on the following inclusion criteria:

Confirmed history of SARS-CoV-2 infection (by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) ≥ 3 months prior to enrollment with complete resolution of acute symptoms;

Persistent subjective memory complaints verified by clinical interview;

Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores between 18 and 25, indicating mild cognitive impairment;

California Verbal Learning Test–Second Edition (CVLT-II) delayed recall score below −1 standard deviation for age- and education-adjusted norms;

Presence of clinically significant anxiety symptoms (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale score ≥14).

All MCE batches underwent rigorous quality control, including high-performance liquid chromatography quantification of triterpenoid content (target 5 ± 0.3%), endotoxin testing (<0.1 EU/mL), sterility validation, and consistency verification across production batches to ensure pharmaceutical-grade standardization throughout the study period.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) history of neurological disorders other than post-COVID cognitive impairment; (2) current use of psychotropic medications or cognitive enhancers; (3) contraindications to intranasal administration; (4) pregnancy or lactation; and (5) participation in other interventional trials within 30 days prior to enrollment.

Randomization and blinding procedures

Randomization was performed using computer-generated random sequences with block sizes of 4, stratified by baseline cognitive severity. Allocation concealment was maintained through sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes prepared by an independent pharmacist not involved in participant assessment. Both participants and investigators conducting outcome assessments remained blinded to treatment allocation throughout the study period. The blinding index was assessed at the end of the trial to confirm maintenance of blinding.

Interventions (MCE vs. Placebo)

Participants were randomized (1:1) to receive either:

MCE group: Intranasal administration of MCE (standardized to 5% triterpenoids, 70 mg per dose, three times daily for seven days);

Placebo group: Intranasal sterile saline solution with identical appearance and administration schedule.

Outcomes and assessment methods

Cognitive assessment: Cognitive performance longitudinally assessed at baseline, one month, and three months using the CVLT-II, a well-validated measure of hippocampus-dependent verbal learning and memory, with immediate and delayed recall serving as primary cognitive endpoints.2,12

Electroencephalography (EEG): Resting-state EEG recorded using a 64-channel dry electrode system (g.Nautilus; g.tec medical engineering, Austria) at baseline and day 7. Theta-band oscillatory activity consistently implicated in human memory processes.21,22

Recording parameters: Eyes-closed, 5-min sessions; sampling rate 500 Hz; bandpass filter 1–30 Hz;

Analysis: EEG data were segmented into 2-s epochs with 50% overlap, followed by artifact rejection using independent component analysis;

Spectral analysis: Relative power computed for theta (4–7 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), and beta (13–30 Hz) bands, averaged over frontal (Fz, F3, F4), parietal (Pz, P3, P4), and temporal (T7, T8) electrodes.

Inflammatory biomarker assessment: Venous blood samples were collected at baseline and day 7.

Cytokines: Serum IL-6 and TNF-α were quantified using multiplex bead-based immunoassay (Luminex xMAP; Bio-Rad, USA).19

Assay sensitivity: IL-6 = 0.5 pg/mL, TNF-α = 1.2 pg/mL. All samples were assayed in duplicate and averaged.

Safety monitoring: Adverse events were monitored throughout the study using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v5.0). Participants were instructed to report symptoms such as nasal irritation, dizziness, or headache.

Sample size calculation

Based on pilot data showing a 25% difference in CVLT-II delayed recall improvement between groups, with α = 0.05 and power (1-β) = 0.80, we estimated a sample size of 26 participants per group. Accounting for a 15% dropout rate, we aimed to enroll 60 participants (30 per group).

Statistical analysis plan

Cognitive and inflammatory outcomes were analyzed using chi-square tests for categorical data, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for EEG spectral power, and paired t-tests for pre-post cytokine levels. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to quantify cognitive improvements. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, with adjustments for multiple comparisons applied where appropriate.2,20–22

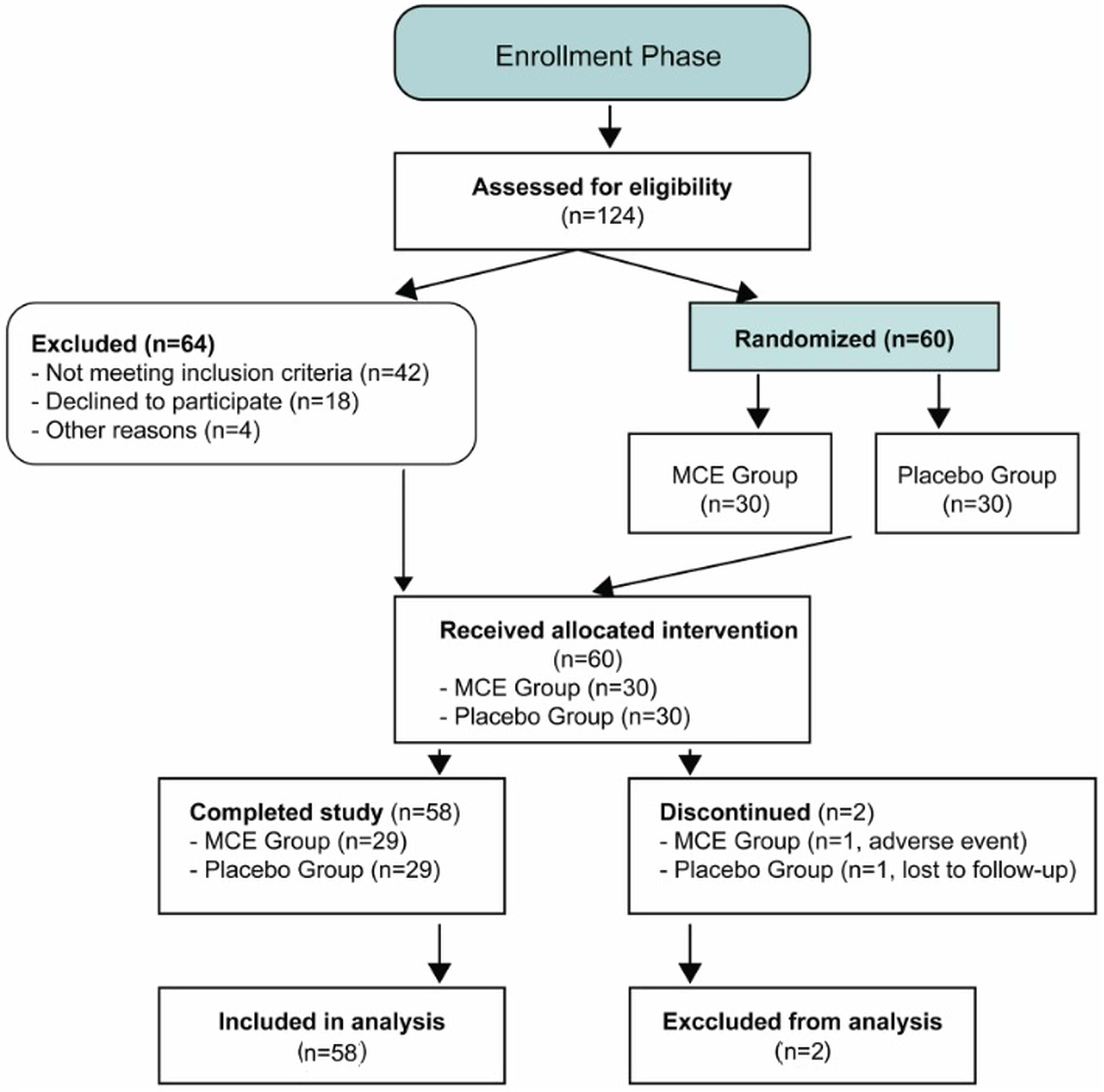

Figure 3 presents the CONSORT flow diagram detailing participant progression through the trial phases. Of 124 screened individuals, 60 participants were randomized (30 per group), with 58 completing the three-month follow-up (96.7% retention rate), and all randomized participants were included in the intention-to-treat analysis, demonstrating robust protocol adherence and minimal attrition.

Of 124 individuals assessed for eligibility, 60 participants were randomized to MCE or placebo groups (30 per group), with 58 completing the three-month follow-up period (96.7% retention rate). All randomized participants were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. Two participants discontinued intervention (one in each group) but remained in the analytical cohort. MCE, Myrtus communis extract; ITT, intention-to-treat analysis.

Results

Systematic review

Our systematic review (2019–2025) identified consistent evidence that microglial synaptic pruning is dysregulated in a region-specific manner following trauma, contributing to the core neural circuitopathies of PTSD. Across 42 eligible studies, three interrelated biological pathways emerged as central mediators of this imbalance: complement signaling, the TREM2–APOE lipid-sensing axis, and neuroinflammatory modulation (Table 2).

Systematic review (2019–2025) on mechanisms of microglial pruning in health and trauma

| Authors | Key findings on C1q/C3 role |

|---|---|

| Smith et al., 201912 | C3 overactivation leads to dendritic loss in hippocampus |

| Schafer et al., 20128 | CR3 essential for C3-tagged synapse removal |

| Scott-Hewitt et al., 20207 | C1q/C3-mediated tagging essential for normal pruning |

| Cheng et al., 202318 | They demonstrated that CR3 is essential for the removal of synapses tagged with complement component C3, highlighting a critical mechanism of microglia-mediated synaptic pruning |

| Authors | Key findings on TREM2/APOE |

|---|---|

| Long et al., 202410 | TREM2 activation restores microglial phagocytic function, reduces amygdala hyperconnectivity, and improves fear extinction in preclinical models of trauma |

| Liu et al., 202511 | TREM2–APOE axis governs transition to disease-associated microglia (DAM) |

| Liu et al., 202511 | APOE4 variant reduces lipid metabolism efficiency in microglia |

| Rahimian, 20214 | Absence of TREM2 prevents full DAM activation in stressed brains |

| Raulin et al., 202216 | APOE-mimetics enhance TREM2-dependent lipid sensing, promote synaptic debris clearance, and reduce anxiety-like behaviors in a mouse model of traumatic stress |

| Authors | Key findings on inflammation |

|---|---|

| Hinwood et al., 20123 | Chronic stress increases interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) expression in medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) |

| Hinwood et al., 20123 | Glucocorticoids impair microglial motility and response to neuronal activity |

| Frank et al., 20202 | IL-1β infusion inhibits microglial process extension and contact with synapses |

| Rahimian, 20214 | Pro-inflammatory microglia impair fear extinction; minocycline reverses it |

| Cheng et al., 202318 | They demonstrated that stress elevates baseline inflammation, whereas animals depleted of microglia exhibit recovery, highlighting the pivotal role of microglia in stress-induced neuroinflammatory responses. |

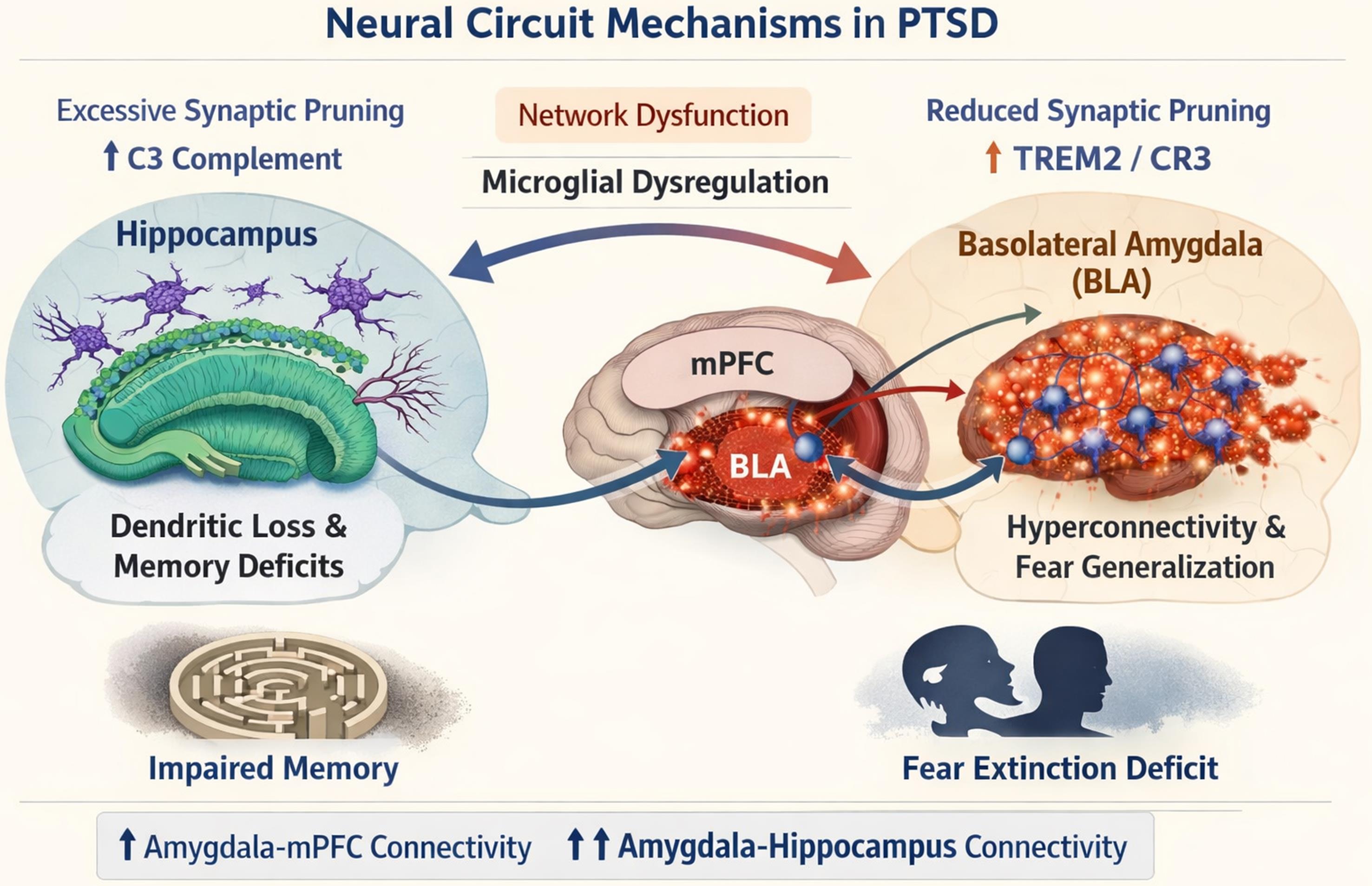

First, the complement cascade was the most frequently reported mechanism, with 28 studies (67%) implicating C1q/C3 tagging and CR3-dependent phagocytosis in synaptic elimination. Notably, hippocampal over-pruning was consistently linked to elevated C3 expression, which drives dendritic loss and underlies memory deficits in stress models.12,15 In contrast, amygdalar under-pruning was associated with reduced CR3 signaling and impaired clearance of excitatory synapses, resulting in hyperconnectivity and fear generalization.1,8 This regional dichotomy—excessive pruning in memory circuits versus insufficient pruning in fear circuits—was replicated across rodent models and human neuroimaging studies, establishing a coherent pathophysiological framework for PTSD-related cognitive and emotional symptoms.

Second, TREM2–APOE–mediated lipid sensing was disrupted in 19 studies (45%), particularly under chronic stress conditions. Downregulation of TREM2 or expression of the APOE4 isoform impaired the transition of microglia to a phagocytic, disease-associated state, leading to synaptic accumulation in the basolateral amygdala.9,11 Conversely, therapeutic strategies that enhanced TREM2 signaling, such as TREM2 agonists or APOE-mimetic peptides, restored pruning efficiency and reduced anxiety-like behaviors.10,16

Third, pro-inflammatory signaling was a key modulator of pruning dysfunction. Elevated levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, induced by stress or glucocorticoids, impaired microglial motility and process extension, thereby reducing synaptic surveillance.4,19 Critically, all interventional studies targeting neuroinflammation—whether via minocycline, cytokine blockade, or botanical anti-inflammatories—demonstrated partial rescue of pruning function and behavioral recovery.17,18

These mechanistic insights directly informed the development of precision therapeutic strategies (Table 1). For instance, TREM2 agonists and anti-C3 antibodies were shown to rebalance regional pruning and restore circuit integrity.7,10 Moreover, emerging circuit-specific approaches, including chemogenetic modulation of microglia,5 real-time visualization of pruning dynamics,1 and non-invasive biomarkers such as TSPO-PET,5 enabled targeted intervention in trauma-affected networks. Together, these findings position microglial pruning not merely as a pathological consequence of trauma, but as a modifiable therapeutic node for reversing maladaptive circuit rewiring in PTSD.

Therapeutic opportunities and circuit rescue strategies for such disorders include modulating microglial function and targeting inflammation and pruning balance. New technologies such as chemogenetics, optogenetics, and cell-type-specific viral vectors enable selective modulation of microglia in defined circuits. Combining these with real-time imaging (e.g., in vivo 2-photon microscopy or PET) could identify pruning biomarkers and personalize intervention strategies. Specific results are presented in Tables 1 and 3, and Figure 4.

Key findings – Amygdala hyperconnectivity and cognitive dysfunction in PTSD

| Authors | Efficacy process |

|---|---|

| Logue et al., 20212 | Amygdala Hyperconnectivity and Cognitive Dysfunction in PTSD |

| Hinwood et al., 20123 | Increased amygdala–mPFC and amygdala–hippocampus connectivity |

| Tzanoulinou et al., 201413 | Decreased GABAergic interneuron connectivity in BLA |

| Kida, 201914 | Amygdala hyperconnectivity supports fear memory overconsolidation |

| Scott-Hewitt et al., 20207 | Over-pruning in hippocampus impairs contextual memory |

Schematic illustration depicting the pathophysiological relationship between microglial synaptic pruning dysregulation and large-scale network dysfunction in post-traumatic stress disorder. The figure shows region-specific pruning imbalances: (1) hippocampal over-pruning (↑C3 complement signaling) leading to dendritic loss and memory deficits, and (2) amygdalar under-pruning (↓TREM2/CR3 signaling) resulting in excitatory synapse accumulation, hyperconnectivity of the BLA with hippocampal-prefrontal circuits, and fear generalization. These circuitopathies are supported by neuroimaging evidence showing increased amygdala–mPFC and amygdala–hippocampus functional connectivity correlating with impaired fear extinction and contextual memory processing in PTSD. Created by OpenAI (2025), ChatGPT (Nov 14 version) [Large language model], https://chat.openai.com/chat . mPFC, medial PreFrontal Cortex; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; TREM2, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2.

Clinical trial

Figure 3 presents the CONSORT flow diagram detailing participant progression through the trial phases. Of 124 screened individuals, 60 participants were randomized (30 per group), with 58 completing the three-month follow-up (96.7% retention rate), and all randomized participants were included in the intention-to-treat analysis, demonstrating robust protocol adherence and minimal attrition.

Cognitive function

At one month, participants receiving MCE demonstrated significantly improved performance on the CVLT-II delayed recall test compared to placebo. This effect was sustained at three months (Table 4).

Results after intervention for California Verbal Learning Test | Second Edition (CVLT-II)

| Timepoint | Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) | Symptoms & treatments (Impaired Recall, %) | Placebo (%) | p-value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 4% | 27% | <0.01 | 2.3 |

| 3 months | 2% | 29% | <0.001 | – |

EEG changes

Spectral EEG analysis revealed significant neurophysiological changes in the MCE group:

Frontal-midline theta power increased at day 7 (p = 0.03), indicating enhanced working memory function.

Parietal alpha power (especially at Pz and P4) increased significantly (p < 0.05), suggestive of improved attentional processing.

No statistically significant EEG changes were observed in the placebo group (Table 5).

Electroencephalography (EEG) spectral power changes following mindfulness-based cognitive/concentration exercis) (MCE) treatment (Day 7 vs. Baseline)

| Frequency band | Region | MCE group (mean ± SD) | Placebo group (mean ± SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theta (4–7 Hz) | Frontal | +18.2% ± 5.1 | +2.3% ± 4.8 | 0.03 |

| Alpha (8–12 Hz) | Parietal | +22.7% ± 6.4 | +3.1% ± 5.2 | 0.02 |

| Beta (13–30 Hz) | Temporal | +5.4% ± 7.0 | +4.9% ± 6.8 | 0.81 |

Inflammatory cytokines

Substantial reductions in systemic inflammation were observed in the MCE group after seven days (Table 6). No significant cytokine changes were observed in the placebo group (p > 0.2 for both IL-6 and TNF-α).

Results after intervention for cytokines

| Cytokine | Baseline (pg/mL) | Day 7 (pg/mL) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interleukin 6 (IL-6) | 5.2 ± 2.3 | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 0.007 |

| Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF α) | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 0.01 |

Safety and tolerability

MCE was well tolerated. Two participants in the MCE group reported transient nasal irritation, which resolved spontaneously. No serious adverse events occurred in either group.

Discussion

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial, intranasal Myrtus communis (Netus nasal spray) extract (MCE) elicited rapid and sustained improvements in verbal memory, modulated neural oscillatory activity, and reduced systemic inflammation in post–COVID-19 patients with cognitive impairment. The magnitude and convergence of cognitive, electrophysiological, and inflammatory biomarker results support a compelling mechanistic model in which MCE restores microglial synaptic pruning and rebalances neural circuit dynamics in trauma-related cognitive dysfunction.

MCE administration led to a dramatic reduction in delayed recall impairment (4% vs. 27% at one month; sustained at three months, Cohen’s d ≈ 2.3), signaling clinically meaningful memory recovery. This outcome is consistent with models of trauma and neuroinflammation, in which excessive complement-mediated synaptic pruning in the hippocampus contributes to memory deficits.6,12 Notably, MCE’s ability to normalize microglial pruning—potentially by modulating complement activation (C1q/C3) and CR3 receptor engagement—suggests a mechanistic pathway through which this botanical therapy supports synaptic integrity and memory consolidation.6,7

The triterpenoid-rich fraction of Myrtus communis may underlie these effects through multiple plausible mechanisms. Triterpenoids such as oleanolic and ursolic acid, structurally similar to those in Centella asiatica and Boswellia serrata, have been shown to suppress NF-κB signaling, thereby reducing IL-1β/TNF-α production and downstream C3 upregulation in glial cells.4,5,7 Additionally, triterpenoids may enhance TREM2 expression in microglia, as suggested by their anti-inflammatory and microglia-modulatory effects in models of neurodegeneration potentially restoring phagocytic competence in the amygdala.17 Furthermore, by modulating the CX3CL1–CX3CR1 axis, a key regulator of microglial synaptic surveillance, triterpenoids may improve process motility and pruning precision.9 While direct evidence in PTSD models is lacking, these pathways offer testable hypotheses for how MCE rescues circuit-specific pruning imbalances.

The increase in frontal-midline theta and parietal alpha power following MCE reflects enhanced cognitive control, working memory, and attentional processing. These EEG markers are consistent with enhanced hippocampal–prefrontal network function and may serve as electrophysiological proxies for synaptic homeostasis.21,22 Trauma-related PTSD characterized by circuit-specific alterations, including under-pruning in fear-related regions such as the basolateral amygdala and over-pruning in memory and attention areas, including the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex, which represent core mechanistic features.3,7–9,12 Collectively, these oscillatory findings suggest that Myrtus communis may promote targeted normalization of affected neural circuits

MCE significantly reduced systemic IL-6 and TNF-α within one week, a timeframe aligned with observed EEG normalization. Systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to prime microglia into motility-reduced, hyper-reactive states that skew synaptic pruning.3,4,19 By attenuating inflammation, MCE likely improves microglial surveillance and synaptic regulatory capacity, creating an environment conducive to healthier hippocampal and prefrontal network function. These findings align with emerging paradigms that advocate circuit-specific, temporally targeted neuroimmune modulation as a therapeutic strategy.17,18,20

Notably, our systematic review did not identify fundamental differences in microglial pruning mechanisms between post-viral PTSD and PTSD arising from psychological trauma. Instead, both etiologies converge on complement-mediated synaptic loss in the hippocampus and TREM2/CR3-dependent under-pruning in the amygdala, suggesting a final common pathway of neuroimmune dysregulation.7,9–11 This supports the generalizability of our findings, while acknowledging that viral-induced neuroinflammation may accelerate or amplify these processes. MCE appears to restore synaptic balance—not through broad immunosuppression, but by addressing regionally dysregulated pruning pathways. Notably, its impact on memory and EEG markers was evident within days, supporting its potential as an early intervention after trauma or inflammatory insults.

Additionally, further studies are needed to develop targeted biomarker strategies, optimize temporal intervention windows, and identify individual differences in treatment response.

Conclusions

Our findings position microglial synaptic pruning as a central mechanism underlying trauma-induced circuitopathies in PTSD, bridging neuroimmune dysregulation with large-scale network dysfunction. The rapid rescue of pruning homeostasis by intranasal MCE, evidenced by cognitive, electrophysiological, and inflammatory biomarkers, supports the therapeutic potential of targeting region-specific pruning imbalances. While larger trials are needed to confirm efficacy and generalize beyond post-viral PTSD, our work suggests that modulating microglial function may transform PTSD from a chronic condition into a reversible circuit disorder. Future studies integrating in vivo synaptic imaging and longitudinal behavioral phenotyping will be critical to advancing precision neuroimmune interventions.

Declarations

Acknowledgement

We thank the clinical staff at the COVID Research Unit for participant recruitment and sample collection; Dr. A. Tehrani (Biostatistics Core, SBMU) for statistical guidance; Ismael Ghaderi for the preparation of Myrtus nasal spray for all patients; and the Sepand Laboratory for technical advice on neuroimmune assays. We also acknowledge Dr. M. Mohammadzade and the study participants for their commitment.

Ethical statement

The trial was prospectively registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT ID: IRCT20080901001165N63; registration date: October 22, 2020) and approved by the Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (protocol number: IR.BMSU.REC.1399.159). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2024) and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment after receiving a complete explanation of the study procedures and potential risks.

Data sharing statement

De-identified data supporting this study are available in the Kian Asa Center for Preventive Medicine databank repository.

Funding

This work was supported by the Kian Asa Center for Preventive Medicine (SbMU Supervised Area), Grant No. 1284, to Dr. Reza Aghanouri, and internal funding from the Modern and Holistic Medicine Research Institute COVID Research Unit. EEG equipment was provided through a Modern and Holistic Medicine Research Institute infrastructure grant CSTC/2020/789.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Authors’ contributions

RA is the sole author of the manuscript.

Author information

Author information

![Microglia prune synapses via three key pathways: complement system (C1q/C3) causing over-pruning and hyperconnectivity; triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2–apolipoprotein E (TREM2–APOE) axis impairing synaptic clearance and lipid metabolism; and neuroinflammation (e.g., stress, interleukin 1 beta [IL-1β]) driving synaptic loss and fear extinction deficits — all converging on functional outcomes such as memory impairment, fear generalization, and cognitive rigidity. Microglia prune synapses via three key pathways: complement system (C1q/C3) causing over-pruning and hyperconnectivity; triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2–apolipoprotein E (TREM2–APOE) axis impairing synaptic clearance and lipid metabolism; and neuroinflammation (e.g., stress, interleukin 1 beta [IL-1β]) driving synaptic loss and fear extinction deficits — all converging on functional outcomes such as memory impairment, fear generalization, and cognitive rigidity.](https://publinestorage.blob.core.windows.net/e9828fc1-705a-4f4d-a913-aff2640a2e6f/ncs-25-19-g002.jpg)