Introduction

Tau protein lies at the heart of a devastating group of neurodegenerative disorders affecting millions of people worldwide, including Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, all of which share a common thread: tau transforms from an essential neuronal protein into a destructive agent.1 Under normal circumstances, tau maintains neuronal stability by preserving the integrity of microtubules that form the cellular highway system for transporting vital materials2; however, when tau becomes hyperphosphorylated and misfolds, it abandons its protective role and begins forming neurofibrillary tangles that ultimately destroy neurons.3 Perhaps the most concerning aspect is tau’s ability to spread from cell to cell, propagating disease throughout interconnected brain networks in a prion-like manner that closely correlates with cognitive decline and clinical progression.4

The brain’s extraordinary energy demands have long fascinated neuroscientists, as this three-pound organ consumes approximately 20% of the body’s total glucose despite representing only 2% of body weight.5 This remarkable metabolic activity reflects the enormous energy requirements of neuronal function, from maintaining membrane potentials to powering synaptic transmission and sustaining the molecular machinery essential for cellular survival, with meeting these demands relying on sophisticated metabolic cooperation between astrocytes and neurons that has evolved to optimize energy delivery precisely where and when it is most needed.6 Astrocytes, once considered merely structural support cells, are now recognized as intricate metabolic coordinators capable of detecting neural activity and responding by enhancing glucose uptake and lactate production,7 ensuring that active neurons receive adequate fuel during periods of peak demand while allowing different brain regions and activity states to adapt to fluctuating energy requirements.8

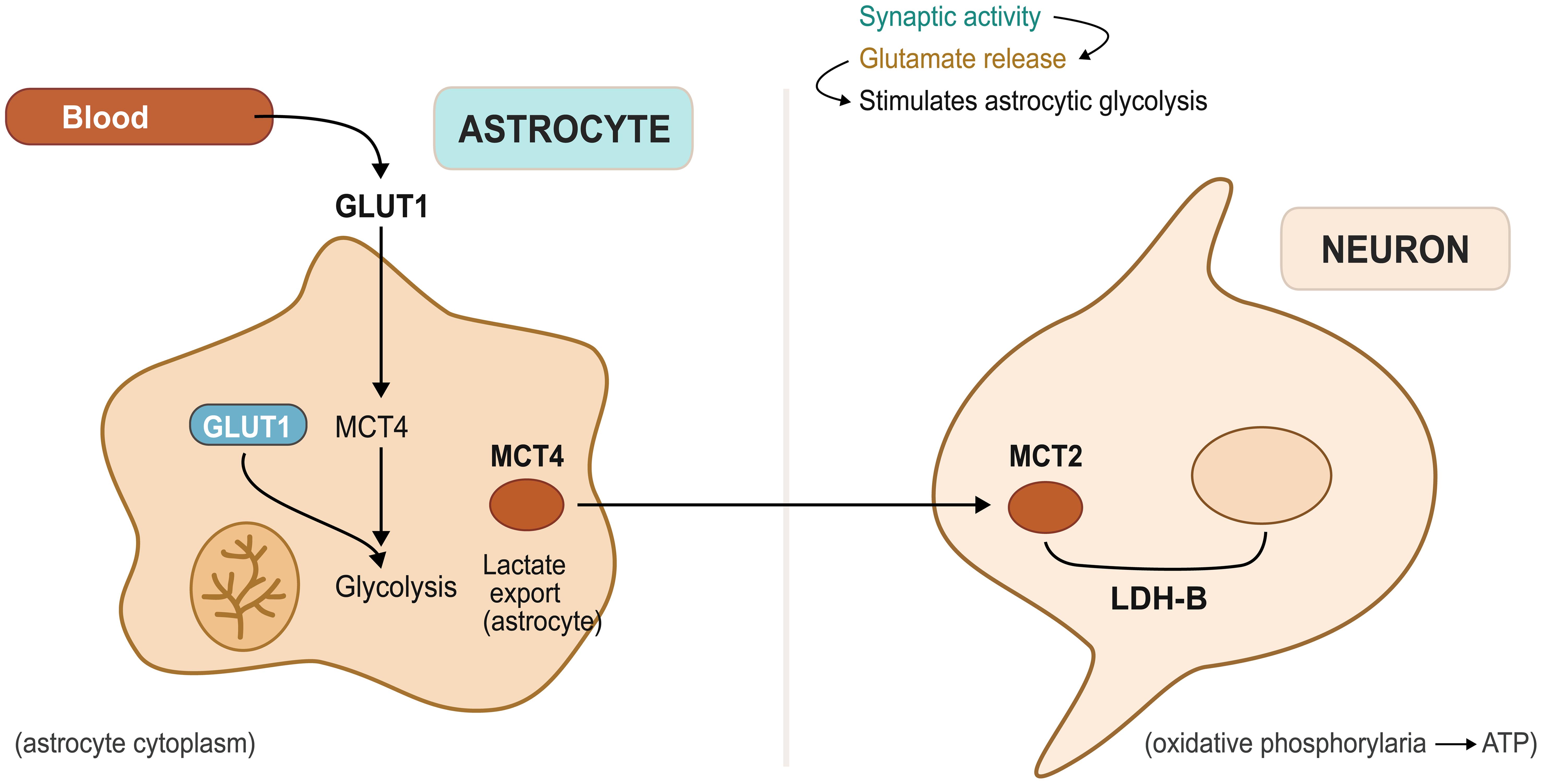

The astrocytic lactate shuttle represents one of neuroscience’s most elegant metabolic discoveries, challenging the traditional view that neurons rely primarily on glucose for energy through a system in which astrocytes preferentially take up glucose from the bloodstream and convert it to lactate through glycolysis, even under oxygen-rich conditions.9 This lactate is then exported via monocarboxylate transporters and taken up by neurons, where it can be rapidly converted to pyruvate and utilized for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production through oxidative phosphorylation as shown in Figure 1.10 This arrangement offers several advantages: astrocytes can rapidly mobilize glucose stores during periods of intense neuronal activity, lactate serves as a more efficient fuel source for neurons under certain conditions, and the system provides metabolic flexibility that allows optimal energy distribution throughout neural networks.11,12 Beyond its role in energy provision, the lactate shuttle functions as a signaling mechanism, with lactate levels conveying information about metabolic status and facilitating adaptive responses to changing energy demands.13

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GLUT, glucose transporter type 1; LDH-B, lactate dehydrogenase isoform B; MCT4, monocarboxylate transporter 4.

The emerging recognition that metabolic dysfunction may drive rather than simply accompany tau pathology represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of neurodegeneration, as traditional approaches have largely focused on tau aggregates as toxic end products while accumulating evidence suggests that energy failure may trigger tau’s pathogenic transformation.14 When the astrocytic lactate shuttle becomes compromised, neurons experience energy deficits that promote cellular stress, disrupt homeostatic balance, and facilitate tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation15—a metabolic vulnerability that may explain why tau pathology preferentially affects brain regions with high energy demands and why metabolic changes often precede detectable tau accumulation in both animal models and human studies. Understanding the metabolic foundations of tau pathology opens new therapeutic possibilities that target the underlying energy crisis rather than merely addressing its protein consequences, potentially leading to more effective interventions for these devastating disorders.

This review aims to comprehensively examine the complex relationship between astrocytic lactate shuttle dysfunction and tau pathology in neurodegenerative diseases. We begin by exploring the astrocytic lactate shuttle in brain metabolism, detailing its fundamental role in neuronal energy supply and the consequences of its disruption. Next, we examine tau pathology and early propagation mechanisms, investigating how tau transforms from a stabilizing protein into a pathogenic agent capable of cell-to-cell transmission. The review then focuses on linking lactate dysfunction to tau propagation, analyzing the molecular pathways through which metabolic failure drives tau misfolding and aggregation. We subsequently discuss experimental and clinical pathways of tau pathology, reviewing evidence from both laboratory models and human studies that demonstrate the metabolic basis of tauopathies. Finally, we address therapeutic implications and future directions, evaluating how targeting the astrocytic lactate shuttle and related metabolic pathways might offer novel treatment strategies for Alzheimer’s disease and other tau-mediated disorders. By synthesizing current research across these domains, this review provides a framework for understanding how metabolic dysfunction serves as both a driver and potential therapeutic target in the complex landscape of neurodegeneration.

The astrocytic lactate shuttle in brain metabolism

The astrocytic lactate shuttle has fundamentally transformed our understanding of brain energy metabolism, as the simplistic view that neurons directly utilize glucose has given way to a more sophisticated appreciation of glial-neuronal metabolic cooperation. This system operates through a coordinated sequence of events initiated by glutamate release at synapses during heightened neuronal activity, which astrocytes detect through specialized receptors and transporters to gauge local energy demands.15 In response, astrocytes rapidly increase glucose uptake from nearby blood vessels, facilitated by glucose transporter 1, which maintains high glucose affinity even at low concentrations.16

Once glucose enters astrocytes, it undergoes glycolysis rather than oxidative metabolism, even under oxygen-rich conditions, though this apparent metabolic inefficiency serves important functional purposes.17 Glycolysis proceeds much more rapidly than oxidative phosphorylation, enabling astrocytes to generate lactate quickly when neurons require immediate energy, while astrocytes simultaneously utilize the pentose phosphate pathway to generate NADPH for biosynthesis and antioxidant defense.18 Furthermore, astrocytic glycolysis provides precursors for neurotransmitter synthesis, particularly glutamine, which is subsequently transferred to neurons for glutamate production.7 The lactate produced through astrocytic glycolysis does not remain within these cells but is exported via specialized transporters, representing a critical component of brain metabolism by controlling neuronal lactate availability.10 Astrocytes express high levels of lactate dehydrogenase and maintain conditions favoring lactate production, while neurons possess greater amounts of enzymes that convert lactate back to pyruvate for oxidative metabolism, creating a division of metabolic labor that enables efficient lactate transfer from producer to consumer cells.7

Monocarboxylate transporters serve as the molecular gatekeepers controlling lactate flux in the brain, with the three main family members each fulfilling distinct roles.19 MCT1 is predominantly expressed on astrocytic processes contacting blood vessels, where it can import lactate from circulation during periods of elevated blood lactate, such as exercise or metabolic stress, though more importantly for local brain metabolism, MCT1 facilitates astrocytic lactate export into the extracellular space.20 This transporter’s high capacity and low lactate affinity make it well-suited for handling the substantial lactate fluxes occurring during intense neuronal activity,21 while MCT2 represents the neuronal component of the lactate shuttle, being primarily localized to neuronal membranes where it imports lactate from the extracellular environment.13 This transporter exhibits higher lactate affinity than MCT1, allowing neurons to efficiently capture lactate even when extracellular concentrations are relatively low,22 and the complementary kinetic properties of MCT1 and MCT2 create a system enabling rapid astrocytic lactate export and efficient neuronal uptake across varying concentration ranges.23 MCT4 adds complexity to brain lactate metabolism, though its role remains less well-defined than the other transporters, as this isoform appears in astrocytes in specific brain regions and under particular conditions, such as development or injury. MCT4 exhibits even lower lactate affinity than MCT1 but can handle very high lactate concentrations, suggesting it may become important when lactate production exceeds the capacity of other transport systems.24

The physiological importance of the lactate shuttle becomes evident during periods of heightened neuronal activity when vascular glucose delivery cannot meet energy demands, particularly since neurons store minimal glycogen compared to astrocytes and require continuous fuel supply. The lactate shuttle not only provides this supply but offers metabolic advantages unavailable through glucose metabolism alone, as lactate can cross the blood-brain barrier more efficiently than glucose under certain conditions, and when neurons are already energy-depleted, lactate metabolism yields more ATP per molecule consumed.25 Beyond energy provision, lactate functions as a signaling molecule facilitating communication between brain regions, with lactate concentrations influencing gene expression in both neurons and astrocytes, leading to protein synthesis supporting neuroprotection and synaptic plasticity.26 The molecule also promotes vasodilation, helping match cerebral blood flow to metabolic demands, while evidence suggests lactate may directly influence synaptic strength and neurotransmitter release,27 though these signaling mechanisms require further investigation.

The lactate shuttle also contributes to brain homeostasis by providing metabolic flexibility across different physiological states, as during sleep, when neuronal activity is reduced, astrocytes can accumulate glycogen stores that can be mobilized for lactate production upon awakening.28 This system helps the brain manage energy storage and utilization during sleep-wake transitions and fluctuating cognitive demands throughout the day.

Tau pathology and early propagation mechanisms

The vital roles that tau protein plays in healthy neurons are tragically compromised in diseased conditions. In healthy circumstances, tau attaches itself to microtubules and aids in the stabilization of these cytoskeletal structures, which act as channels for intracellular movement.29 The protein has several binding domains that interact with tubulin, with phosphorylation at particular locations controlling how the protein associates with microtubules, while normal tau phosphorylation enables dynamic control of microtubule stability, responding to cellular activity and following circadian rhythms.30 The movement of organelles, vesicles, and other cellular constituents along microtubules is facilitated by tau’s involvement in axonal transport regulation.31 Furthermore, tau may have more cellular functions than previously thought, as evidenced by recent studies identifying roles for the protein in nuclear processes and synaptic function.32

Tau undergoes multiple significant molecular alterations that usually start with hyperphosphorylation in order to change from a cellular helper to a pathological agent. In disease states, tau loses its ability to bind microtubules efficiently because it is phosphorylated at many normally unaltered sites.33 Detaching from microtubules, this hyperphosphorylated tau starts to accumulate in the cytoplasm, where it can interact with other tau molecules. Conformational changes in the detached tau reveal areas that are typically hidden within the protein structure, forming surfaces that facilitate interactions between proteins.34 Subsequently, these misfolded tau species begin to form small oligomers, which are among the most harmful protein forms. As tau oligomers accumulate, they may act as seeds for additional tau aggregation, recruiting more tau molecules into expanding fibrils.35 Over time, these fibrils develop into neurofibrillary tangles, which are the defining pathological characteristic found in post-mortem brain tissue, though the formation of tangles may actually represent a protective cellular response, as neurons appear to sequester toxic tau species into these comparatively inert deposits.36 The most harmful tau forms likely occur in the transitional stages between normal protein and mature tangles, when tau retains some mobility but develops pathological characteristics.4

Understanding how tau spreads between neurons has become a major focus of research because this process appears essential to disease development. Multiple pathways are available for tau to exit neurons, including packaging into extracellular vesicles, release during cell death, or direct translocation across membranes. Once tau has entered the extracellular space, it can be absorbed by nearby neurons via endocytosis or other internalization processes. Significantly, even minute amounts of pathological tau introduced into healthy neurons can induce endogenous tau misfolding, resulting in a prion-like propagation process.37 Tau transmission appears to be facilitated by synaptic connections, as pathological tau preferentially spreads along anatomically connected brain regions, and this trans-synaptic spread can explain the predictable patterns of tau pathology, which resemble functional brain networks.38 The process exhibits some selectivity, as some synaptic connections appear more susceptible to tau transmission than others, while factors that affect synaptic activity, such as cellular stress and metabolic state, can alter tau propagation efficiency.

At synaptic terminals, where tau typically aids in regulating synaptic vesicle dynamics, the first noticeable alterations in tau aggregation frequently occur. Under stress conditions, tau may mislocalize from axons to cell bodies and dendrites, ending up in cellular compartments where it should not be present. This mislocalization may encourage aggregation and facilitate pathological interactions with other cellular proteins. Compromised protein clearance processes, such as autophagy and proteasomal degradation, also facilitate tau accumulation by prolonging the half-life of damaged proteins.39 The vulnerability of various brain regions to tau pathology varies, following patterns that reflect both metabolic demands and anatomical connectivity, with the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus being among the first regions affected in Alzheimer’s disease due to their high levels of connectivity and metabolic activity. Moreover, these areas exhibit strong synaptic activity and high tau expression, which may increase their susceptibility to tau-related dysfunction. Tau pathology can also begin in the brainstem and basal forebrain, which contain neurons with widespread projections throughout the brain, before spreading to other areas.40

Additionally, regional vulnerability correlates with local factors such as baseline levels of cellular stress, the expression of protective proteins, and the presence of particular neuronal subtypes. Regions with high iron content, increased oxidative stress, or decreased antioxidant capacity may be more prone to tau aggregation.41 The metabolic profiles of different brain regions, including their dependence on particular energy substrates and capacity for metabolic adaptation, likely influence their susceptibility to tau pathology, which helps explain how metabolic dysfunction may accelerate tau spreading in vulnerable neural networks.

Linking lactate dysfunction to tau propagation

Studies have demonstrated that energy deficits can directly cause tau hyperphosphorylation through various cellular pathways, establishing a critical link between metabolic stress and tau pathology.42 When neurons experience ATP depletion, the balance between kinases and phosphatases shifts drastically in favor of phosphorylation, primarily because many phosphatases require substantial energy to remain active, particularly protein phosphatase 2A, which typically dephosphorylates tau.43 Concurrently, under low-energy conditions, stress-activated kinases such as glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) become hyperactive, and as one of the main kinases responsible for pathological tau phosphorylation, GSK-3β activation during metabolic stress promotes tau hyperphosphorylation at disease-relevant sites.44 Additional kinases involved in this metabolic stress response include AMP-activated protein kinase and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5). CDK5 becomes dysregulated when its regulatory protein p35 is cleaved to p25 under stress conditions, resulting in prolonged kinase activation and excessive tau phosphorylation, while chronic activation of AMP-activated protein kinase, though typically protective during energy stress, can also phosphorylate tau at specific sites.45 The convergence of these multiple kinase pathways during metabolic stress creates tau hyperphosphorylation, suggesting that maintaining adequate energy supply may prevent this pathological cascade.

Energy depletion affects tau aggregation through mechanisms beyond simple hyperphosphorylation, as ATP depletion compromises the function of molecular chaperones that normally support proper protein folding and prevent aggregation.46 Heat shock proteins and other chaperone systems require considerable energy to refold misfolded proteins or target them for degradation, and when ATP levels decline, these protective mechanisms become less effective, allowing hyperphosphorylated tau to persist and accumulate.47 Energy depletion also affects cellular quality control mechanisms that normally eliminate damaged proteins, including the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy pathways.48 The cellular stress response to energy depletion further promotes tau aggregation, as endoplasmic reticulum stress, which frequently accompanies metabolic dysfunction, can induce tau misfolding and aggregation through multiple mechanisms.49 Stressed cells often exhibit altered calcium homeostasis, and increased intracellular calcium can activate calpains and other proteases that damage tau and promote its aggregation. The oxidative stress that typically follows energy depletion can directly modify tau by oxidizing cysteine residues, producing cross-linked tau species that resist natural clearance mechanisms.50

Studies analyzing brain tissue from patients with tau-related disorders consistently demonstrate evidence of impaired astrocytic function prior to extensive neuronal loss. In affected brain regions, astrocytes exhibit decreased expression of key glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes, limiting their capacity to uptake glucose and produce lactate.51 Disease-associated astrocytes show morphological changes, including reduced process complexity and altered positioning relative to blood vessels, which likely impairs their ability to detect and respond to neuronal energy demands.52 These structural alterations may result from direct tau toxicity, since astrocytes can uptake pathological tau from neurons and develop their own aggregation pathology.

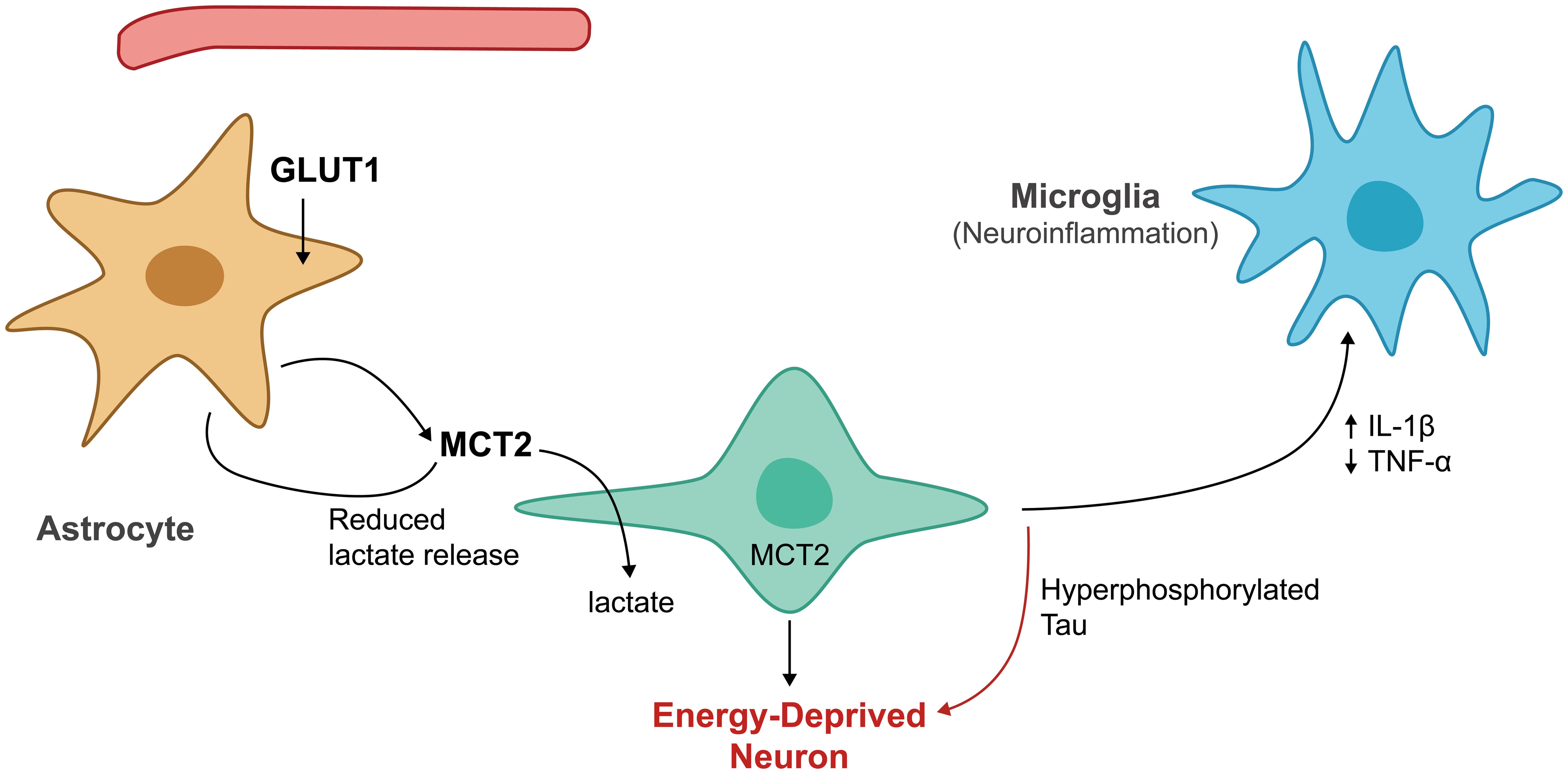

Impaired astrocytic lactate production creates a vicious cycle, where reduced energy supply promotes further tau pathology. Because neurons become increasingly dependent on astrocytic lactate during periods of high activity, any reduction in lactate availability forces neurons to rely more heavily on their limited glucose uptake capacity (Fig. 2).53 This metabolic stress may trigger the tau phosphorylation cascades described above, generating more pathological tau that can subsequently spread to neighboring cells, including astrocytes. The result is progressive deterioration of local energy metabolism that accelerates tau spreading throughout interconnected brain networks.54 Monocarboxylate transporter dysfunction compounds these problems by disrupting lactate transfer even when astrocytes retain some lactate production capacity.25 Research has demonstrated that neurons from tau-affected brain regions show reduced MCT2 expression, limiting their ability to uptake lactate, while astrocytic MCT1 function may also deteriorate, reducing lactate export efficiency. These transporter defects create metabolic bottlenecks that prevent neurons from accessing adequate energy substrates, perpetuating the energy crisis underlying tau pathology.55

GLUT1, glucose transporter type 1; IL-1β, interleukin-1 beta; MCT2, monocarboxylate transporter 2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

The neuronal energy crisis resulting from lactate shuttle dysfunction manifests in numerous ways that directly contribute to tau pathology progression. Neurons experiencing chronic energy deficits show altered calcium handling that can activate calcium-dependent kinases responsible for tau phosphorylation.56 Energy-depleted neurons also exhibit impaired axonal transport, which may cause tau to mislocalize from axons to cell bodies and dendrites, where it can interact with other cellular proteins and promote aggregation. Reduced ATP availability limits the function of ATP-dependent ion pumps, causing membrane depolarization that may trigger excitotoxic cascades.57 Synaptic dysfunction represents another consequence of the neuronal energy crisis that could accelerate tau spreading. Energy-depleted synapses show reduced synaptic vesicle recycling efficiency and altered neurotransmitter release patterns, modifications that may facilitate trans-synaptic tau transmission and promote tau mislocalization to synaptic terminals. Additionally, metabolic stress at synapses may trigger local tau aggregation, creating seeds that can spread to neighboring neurons and cellular compartments.32

Inflammatory responses provide another crucial link between metabolic dysfunction and tau pathology. Energy-depleted neurons release damage-associated molecular patterns that activate microglia and initiate inflammatory cascades. Activated microglia produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α, which can directly promote tau hyperphosphorylation by activating stress kinases.58 These cytokines also worsen the metabolic crisis by impairing astrocytic function, reducing their glucose uptake and lactate production capacity.59 The inflammatory response to metabolic stress includes reactive oxygen species production and complement activation, which can cause direct damage to tau protein and other cellular components. Chronic neuroinflammation creates a positive feedback loop, where metabolic dysfunction promotes inflammation, which in turn accelerates tau pathology and further impairs metabolic function. This inflammatory amplification may explain why tau pathology tends to spread rapidly once established in vulnerable brain regions.60 Astrocyte activation in response to tau pathology further disrupts normal metabolic function, as reactive astrocytes show altered gene expression patterns that reduce their capacity for normal metabolic support functions and increase inflammatory molecule production.61 These changes may persist long after the initial insult, even without ongoing acute stress, creating lasting metabolic deficits that sustain tau pathology.

Experimental and clinical pathways of tau pathology

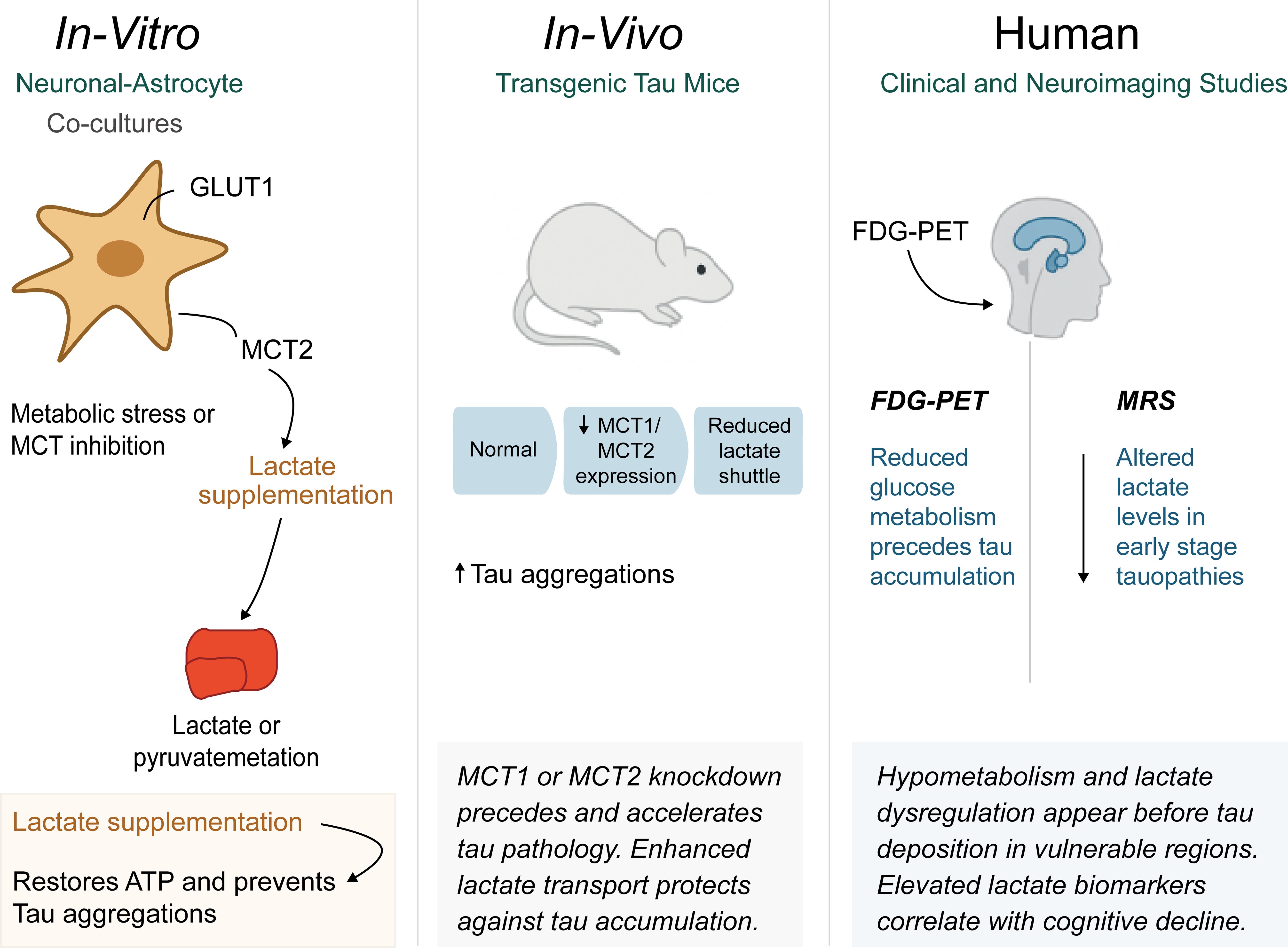

Numerous important discoveries in cell culture research have demonstrated the causal links between energy deficiency and tau aggregation, providing compelling support for the metabolic foundation of tau pathology. Primary neuronal cells subjected to mitochondrial inhibitors or glucose restriction routinely exhibit rapid tau hyperphosphorylation within hours of treatment, with these studies showing that metabolic stress activates specific kinase cascades, particularly GSK-3β and CDK5, which phosphorylate tau at the same sites observed in human disease.62 Critically, providing alternative energy substrates such as lactate or pyruvate can prevent or reverse tau hyperphosphorylation in these models, directly supporting the protective role of astrocytic lactate supply.63

Co-culture experiments with neurons and astrocytes have demonstrated the impact of metabolic coupling on tau pathology. When astrocytes are specifically damaged or their glucose metabolism is compromised, tau pathology develops in co-cultured neurons even when adequate glucose is present in the culture medium.64 These findings demonstrate that neurons cannot fully compensate for reduced astrocytic metabolic support, emphasizing the critical importance of the lactate shuttle. Conversely, enhancing astrocytic lactate production through genetic or pharmacological approaches protects neurons from tau pathology induced by various stressors.65 Animal model experiments have extended these findings to more complex systems that better recapitulate human disease, as transgenic mice expressing human tau show early metabolic changes, including reduced glucose utilization and altered lactate metabolism in vulnerable brain regions, before overt tau pathology appears. When these animals are subjected to metabolic stress through pharmacological inhibition of glycolysis or dietary restriction, tau pathology is significantly accelerated. Studies using microdialysis for real-time brain lactate measurement have revealed that tau transgenic mice exhibit diminished lactate responses to neuronal activity, indicating dysfunction in the astrocytic lactate shuttle.66

Animal studies manipulating monocarboxylate transporters provide particularly compelling evidence, as mice with reduced MCT2 expression show increased vulnerability to tau pathology, while MCT2 overexpression provides protection.67 Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of MCT1 in astrocytes accelerates tau aggregation in vulnerable brain regions. These studies directly link lactate transport dysfunction to tau pathology development while suggesting potential therapeutic targets. Human neuroimaging studies have also revealed that metabolic changes frequently precede detectable tau accumulation by years.68 Positron emission tomography studies using fluorodeoxyglucose consistently show reduced glucose metabolism in brain regions that subsequently develop tau pathology. These hypometabolic patterns appear early in the disease course and correlate with subsequent cognitive decline. More sophisticated imaging approaches using magnetic resonance spectroscopy have provided direct evidence of lactate shuttle dysfunction in human disease by detecting altered lactate levels in the brains of patients with early-stage tau disorders.69

Recent advances in tau positron emission tomography imaging have enabled researchers to directly correlate metabolic changes with tau deposition patterns. These studies show that metabolic dysfunction often precedes tau accumulation in specific brain regions, supporting the hypothesis that energy failure drives rather than simply results from tau pathology.69 The regional patterns of metabolic dysfunction also predict subsequent sites of tau pathology, providing crucial insights into disease progression mechanisms. Biomarker studies have identified numerous metabolic indicators that correlate with tau disease progression, as patients with tau-related disorders show elevated cerebrospinal fluid lactate levels, which may reflect either compensatory increases in astrocytic lactate production or impaired neuronal lactate utilization.53 Plasma metabolomics studies have revealed signatures of disrupted glucose and lactate metabolism that can distinguish tau disease patients from healthy controls. These metabolic biomarkers often show stronger correlations with cognitive symptoms than traditional tau protein measurements, suggesting they may provide more functionally relevant disease indicators.70

Post-mortem brain tissue studies have validated many findings from animal models and imaging studies, showing that patients with tau disorders exhibit reduced astrocytic expression of key glycolytic enzymes and decreased levels of monocarboxylate transporters. These molecular changes are most pronounced in brain regions with the highest tau burden, supporting the connection between metabolic dysfunction and tau pathology.71 Therapeutic research targeting metabolic pathways has shown promising results in animal models and early human studies. Ketogenic diets, which provide alternative fuel sources that bypass glucose metabolism, have demonstrated protection in tau transgenic mice, while direct lactate supplementation or treatments that enhance astrocytic lactate production have also shown neuroprotective effects.72 Several studies have investigated compounds that enhance monocarboxylate transporter function, with encouraging results in slowing tau pathology progression (Fig. 3).

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; FDG-PET, fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; GLUT1, glucose transporter type 1; MCT, monocarboxylate transporter; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; Tau, microtubule-associated protein tau.

Therapeutic implications and future directions

The metabolic origins of tau pathology have sparked innovative therapeutic approaches that target energy deficits rather than protein aggregation alone. Lactate supplementation offers direct neuroprotection by readily crossing the blood-brain barrier, with clinical trials currently investigating intravenous lactate infusions for cognitive decline. Complementary strategies include enhancing astrocytic lactate production through glycolytic enzyme activators and optimizing monocarboxylate transporter function to improve lactate shuttling efficiency. While combined metabolic interventions may prove superior to single treatments, significant challenges remain, including blood-brain barrier penetration, disease heterogeneity, and determining optimal timing before irreversible neuronal loss occurs.73Table 1 below highlights the promising therapeutic strategies targeting the astrocyte-neuron metabolic axis in tauopathies.8,20–22,25,26,33,42,45,49,58,60–72,74,75

Promising therapeutic strategies targeting the astrocyte-neuron metabolic axis in tauopathies

| Therapeutic strategy | Mechanism of action | Target | Preclinical evidence | Clinical status | Potential advantages | Key challenges | Representative references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct lactate supplementation | Bypasses astrocytic lactate production; provides direct neuronal fuel | Neuronal energy deficit | Neuroprotection in tau transgenic mice; reduced tau hyperphosphorylation in cell culture | Phase I/II trials for cognitive decline | Crosses blood-brain barrier; immediate energy supply; well-tolerated | Optimal dosing; delivery timing; systemic effects | Cai et al., 202225; Yang et al., 202465; Magistretti & Allaman, 201826 |

| Ketogenic diet/Ketone bodies | Alternative fuel source bypassing glucose metabolism | Mitochondrial energy production | Protection in tau mouse models; improved cognitive function | Clinical trials in AD and other dementias | Established safety profile; multiple metabolic benefits | Patient compliance; metabolic adaptation; contraindications | Sridharan & Lee, 202272; Robbins, 202442; Wu et al., 202568 |

| MCT1 enhancers | Increase astrocytic lactate export capacity | Astrocyte-to-extracellular lactate transport | Enhanced lactate availability; reduced tau pathology in models | Preclinical development | Targets rate-limiting step; preserves natural shuttle | Specificity; potential off-target effects | Jha & Morrison, 202022; Zhang et al., 202220; Ueno et al., 202321 |

| MCT2 modulators | Improve neuronal lactate uptake efficiency | Neuronal lactate import | Overexpression protects against tau toxicity; pharmacological activation reduces pathology | Early preclinical stage | Direct neuronal benefit; high therapeutic selectivity | Blood-brain barrier penetration; receptor specificity | Batenburg et al., 202364; Ueno et al., 202321 |

| Glycolytic enzyme activators | Enhance astrocytic glucose metabolism and lactate production | Astrocytic glycolysis | Increased lactate output; protection against metabolic stress | Preclinical development | Addresses root cause; supports natural metabolic coupling | Enzyme selectivity; metabolic balance; tissue specificity | Yang et al., 202465; Beard et al., 20218; Wu et al., 202568 |

| AMPK modulators | Regulate cellular energy sensing and metabolic adaptation | Cellular energy homeostasis | Mixed effects: protective at low doses, detrimental with chronic activation | Preclinical optimization | Established metabolic regulator; multiple pathways | Dose-dependent effects; temporal considerations | Requejo-Aguilar, 202345; Tu-Sekine & Kim, 202274 |

| GSK-3β inhibitors | Prevent stress-activated tau hyperphosphorylation | Kinase-mediated tau phosphorylation | Reduced tau pathology in multiple models; improved cognitive outcomes | Phase II trials (some discontinued) | Direct tau target; proven efficacy | Safety concerns; off-target effects; developmental toxicity | D’Mello, 202162; Rawat et al., 202233; Vyas et al., 202463 |

| Anti-inflammatory approaches | Reduce microglia activation and inflammatory cascade | Neuroinflammation secondary to metabolic stress | Reduced tau spreading; preserved metabolic function | Various stages (NSAIDs, specific inhibitors) | Breaks inflammatory amplification cycle | Timing-dependent efficacy; immune system effects | Arnsten et al., 202558; Zhang et al., 2024,75 Jiwaji et al., 202261 |

| Antioxidant therapies | Protect against oxidative damage from energy crisis | Reactive oxygen species and cellular stress | Prevention of tau oxidation and cross-linking; preserved transporter function | Mixed clinical results | Addresses multiple pathways; established safety | Limited bioavailability; timing considerations | Atlante et al., 202160; Ekundayo et al., 202449 |

| Combination metabolic therapy | Multi-target approach addressing energy supply, transport, and utilization | Multiple nodes in metabolic network | Synergistic effects in preclinical studies; superior to monotherapy | Conceptual stage | Comprehensive metabolic support; personalized approach | Complexity; drug interactions; regulatory challenges | Meng et al., 202467; Sun et al., 202466 |

| Biomarker-guided precision therapy | Personalized treatment based on individual metabolic profile | Patient-specific metabolic vulnerabilities | Proof-of-concept studies identifying metabolic subtypes | Research phase | Optimized therapeutic matching; reduced treatment failures | Biomarker validation; diagnostic complexity; cost considerations | Dong et al., 202470; Endepols et al., 202269 |

| Exercise and lifestyle interventions | Enhance natural lactate shuttle function and metabolic flexibility | Systemic metabolic improvement | Improved cognitive outcomes; enhanced lactate metabolism | Ongoing clinical trials | Non-pharmacological; broad health benefits; cost-effective | Patient compliance; disease stage limitations; standardization challenges | Meng et al., 202467; Zhang et al., 202171 |

Future research should prioritize developing biomarkers for patient selection and personalized therapeutic approaches based on individual metabolic genetics.

Conclusions

The emerging paradigm connecting astrocytic lactate shuttle dysfunction to tau propagation fundamentally transforms our therapeutic approach to neurodegenerative diseases. Rather than viewing metabolic changes as secondary consequences of protein pathology, the evidence presented here identifies energy failure as a primary driver of tau aggregation and spreading. This metabolic foundation of neurodegeneration offers unprecedented therapeutic opportunities that address root causes rather than downstream manifestations of disease. The convergence of findings from molecular studies, animal models, and human imaging data substantiates the critical importance of prioritizing metabolic interventions in clinical development. The early appearance of metabolic dysfunction relative to tau accumulation provides a crucial therapeutic window for interventions that could prevent disease progression rather than merely slow its advance. As we move toward precision medicine approaches, understanding individual metabolic vulnerabilities may enable targeted interventions that correct the specific energy deficits driving tau pathology in different patients, potentially transforming the treatment landscape for millions affected by tau-related neurodegenerative disorders.

Declarations

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge all contributors to this comprehensive review examining the metabolic foundations of tau pathology in neurodegenerative diseases. We express our sincere gratitude to the technical staff of the Department of Anatomy, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, for their valuable technical assistance and provision of laboratory resources used in this review. We also thank Genomac Institute Inc. for access to specialized research materials and equipment that supported this work. Special appreciation goes to the native language and editorial experts who provided constructive suggestions that greatly improved the clarity and quality of the manuscript. We also acknowledge the ongoing efforts of clinicians and researchers worldwide who continue to advance our understanding of tauopathies and develop innovative therapeutic approaches targeting metabolic pathways.

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5 model) and related AI-assisted tools to support figure conceptualization and refinement, ensuring accuracy and consistency with the manuscript’s scientific content. AI tools were also used for language clarity and grammar correction. The figures were generated using AI-assisted illustration but were not solely created by AI—all designs were based on the authors’ conceptual frameworks, literature references, and subsequent manual review and editing. The authors have thoroughly verified and approved all AI-assisted content and take full responsibility for the accuracy, originality, and integrity of the published work.

Funding

This review received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

Three authors (Darasimi Racheal Olorunlowu, Ayomikun Motunrayo Ojo and Adetola Esther Abisona) are affiliated with Genomac Institute Inc. While the research received support from Genomac Institute Inc. as acknowledged, the authors declare that this affiliation did not influence the design, conduct, analysis, or interpretation of this review. The authors have no competing financial interests or other conflicts of interest to disclose related to this work.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization (DRO, OOA), literature search and review (DRO, AMO, PMO, GDO, AEA), theoretical framework development (DRO), drafting of the manuscript (DRO, AMO, PMO, GDO, AEA), critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (AMO, PMO, GDO, AEA, OOA), and study supervision (OOA). All authors have made significant contributions to this study and have approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Author information