Introduction

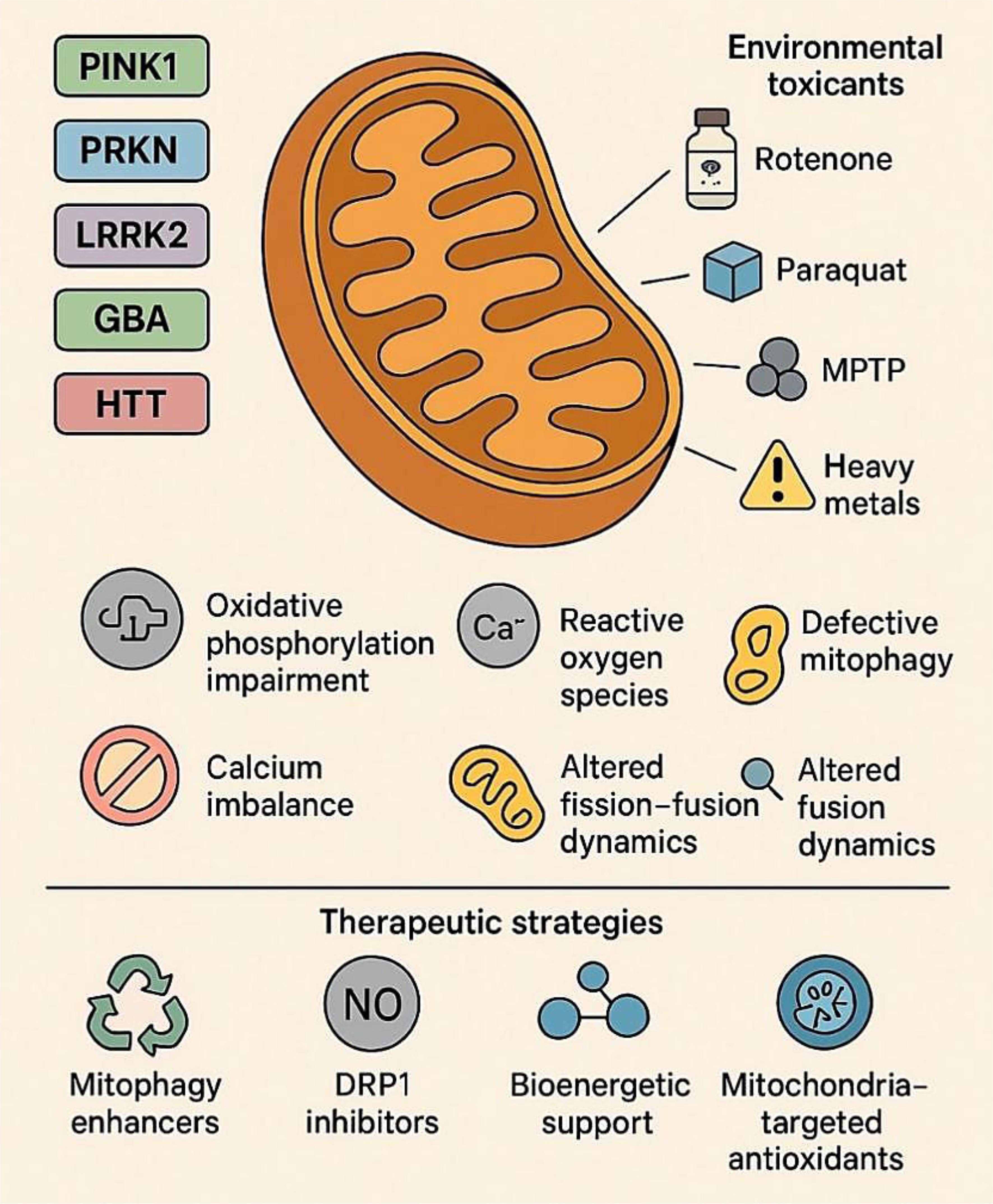

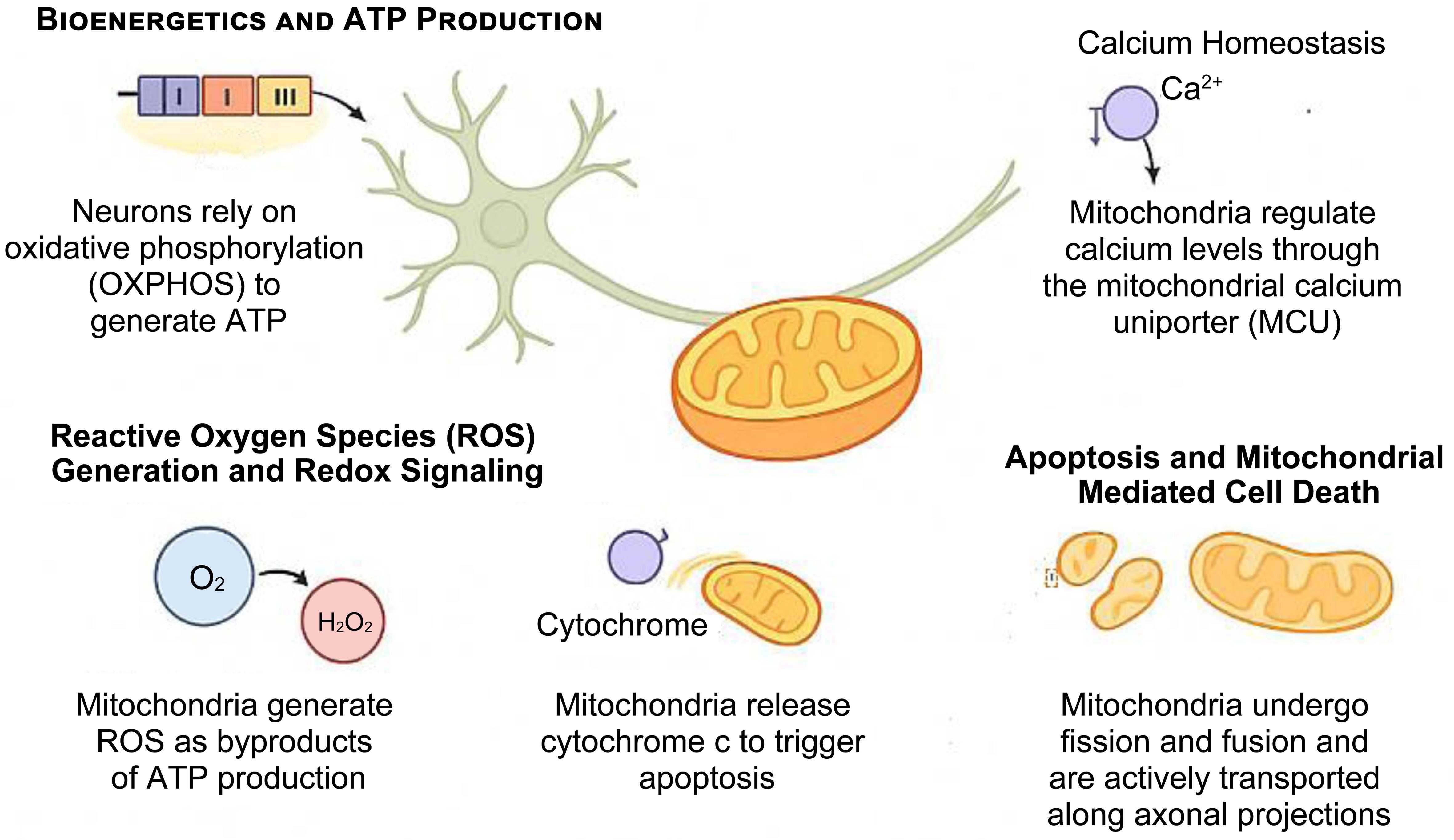

Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD) are progressive and debilitating conditions characterized by selective neuronal loss and central nervous system dysfunction.1 Despite distinct genetic etiologies and clinical presentations, both diseases share a central pathological hallmark: mitochondrial dysfunction. As central hubs of energy metabolism, redox regulation, calcium buffering, and cell death signaling, mitochondria are particularly critical for neurons, which have high metabolic demands and limited regenerative capacity.2,3 Early studies of mitochondrial involvement in neurodegeneration focused on discrete processes such as deficits in adenosine tri phosphate (ATP) production or increased oxidative stress.4 However, it is now clear that mitochondria do not operate in isolation but are dynamically regulated by a complex network of genetic, environmental, and intracellular signals.5 This network, referred to herein as the mitochondrial interactome, encompasses both intrinsic factors, such as mutations in nuclear and mitochondrial genes, and extrinsic influences, including exposure to neurotoxicants and inflammation.6 Disruptions to this tightly regulated system can trigger a cascade of pathological events, ultimately leading to neuronal injury and death.7 In PD, mutations in genes such as PINK1, PRKN (Parkin), DJ-1, and LRRK2 disrupt key aspects of mitochondrial quality control, including mitophagy, redox homeostasis, and mitochondrial dynamics.8 These genetic vulnerabilities are exacerbated by environmental toxins such as rotenone, paraquat, and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) (structures shown in Fig. 1), which inhibit mitochondrial respiratory complexes and potentiate oxidative stress.9–12

The mitochondrial neurotoxins MPTP, Rotenone, and Paraquat are commonly used in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease, where they inhibit mitochondrial respiratory complexes, disrupt redox balance, and induce oxidative stress, thereby phenocopying the mitochondrial quality control deficits caused by mutations in genes such as PINK1, PRKN, DJ-1, and LRRK2.10–12

Similarly, in HD, the expanded Cytosine–Adenine–Guanine trinucleotide (CAG) repeat in the HTT gene produces a mutant huntingtin protein, which disrupts mitochondrial trafficking, oxidative phosphorylation, and calcium handling.13 Although environmental links in HD are less well defined than in PD, accumulating evidence suggests that factors such as metal exposure, stress, and dietary deficiencies may modulate disease progression via mitochondrial pathways.3

Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction in PD and HD extends beyond organellar defects to include impaired signaling, biogenesis, proteostasis, and inter-organelle communication. These disruptions collectively compromise cellular energy homeostasis, exacerbate excitotoxic and inflammatory stress, and promote the accumulation of toxic proteins. Mitochondria thus serve as both sensors and amplifiers of neuropathological stress, integrating genetic susceptibilities and environmental exposures.9 This review aims to integrate current knowledge on how genetic mutations, environmental toxicants, and mitochondrial signaling pathways converge in the pathogenesis of PD and HD. By framing neurodegeneration through the lens of the mitochondrial interactome, we seek to highlight shared molecular mechanisms, identify potential therapeutic targets, and propose new directions for precision medicine approaches in neurodegenerative disease management.

Mitochondrial function in neurons

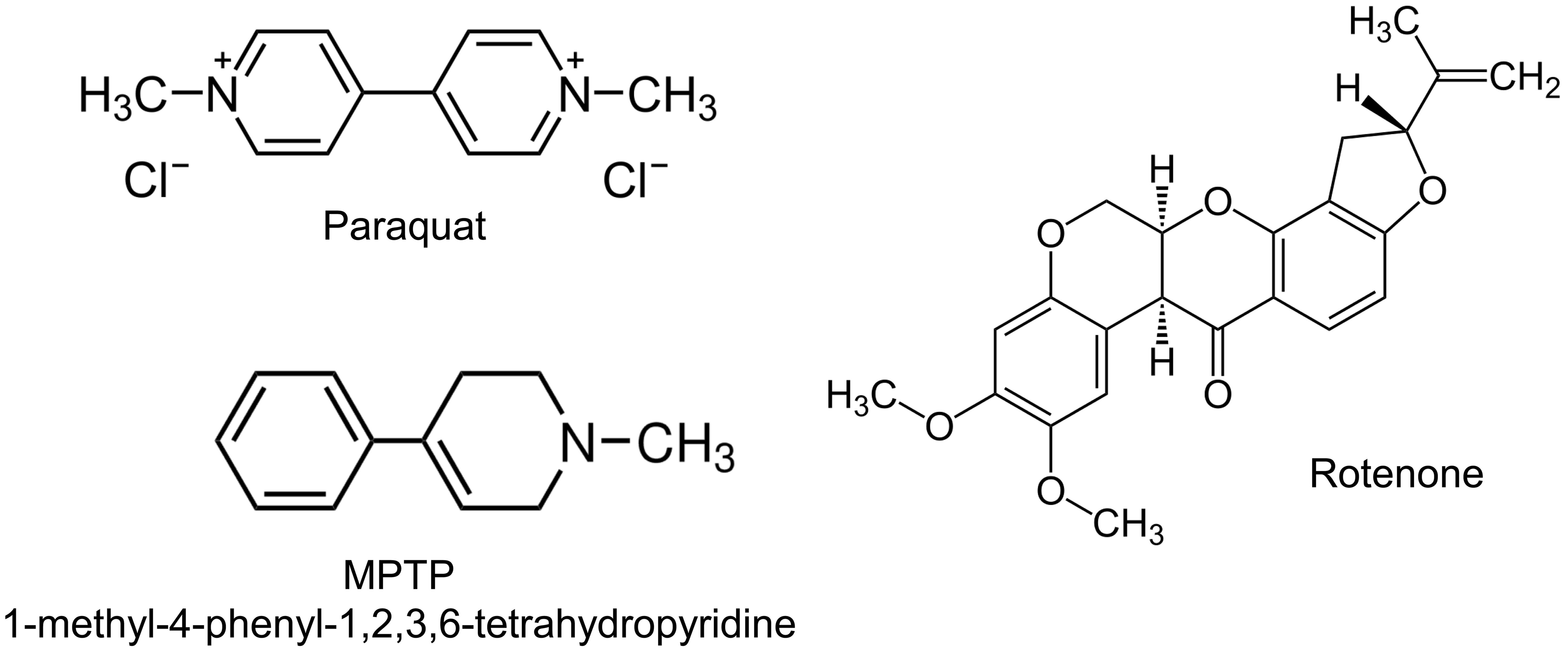

Neurons are uniquely reliant on mitochondria due to their polarized structure, terminal differentiation, and high metabolic activity. Sustained ATP generation and tight regulation of calcium are essential for synaptic transmission, plasticity, and survival (Fig. 2).14–18 Even subtle perturbations in mitochondrial function can undermine neuronal viability, rendering mitochondria central players in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as PD and HD.3,6 Importantly, mitochondrial dysfunction is not confined to neurons. Glial cells—including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia—also exhibit impaired bioenergetics, redox imbalance, and altered mitochondrial signaling, which exacerbate neuroinflammation, impair metabolic support, and accelerate disease progression.19,20 In astrocytes, deficits in mitochondrial metabolism reduce glutamate clearance and lactate shuttling to neurons, while in microglia, altered mitochondrial dynamics drive excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.21–23 A critical determinant of mitochondrial health across both neuronal and non-neuronal populations is the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). This electrochemical gradient is essential for oxidative phosphorylation, calcium buffering, and regulation of reactive oxygen species.24,25 Recent studies demonstrate that collapse of ΔΨm occurs as an early event in PD and HD, preceding overt neurodegeneration, and has been detected in patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models and advanced neuroimaging studies. Thus, ΔΨm has emerged as a sensitive biomarker for mitochondrial dysfunction and a potential therapeutic target in neurodegenerative disorders.26–28

This schematic illustrates the major roles of mitochondria in neurons. Mitochondria sustain neuronal activity through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)–mediated adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, regulate intracellular calcium via the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), and modulate redox signaling by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS). Mitochondria also govern intrinsic apoptosis by releasing cytochrome c and maintain their own health via dynamic processes such as fission, fusion, and motility. Disregulation of these functions contributes to neuronal vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease.16–18

Bioenergetics and ATP production

Neurons rely heavily on oxidative phosphorylation for energy. Mitochondria generate ATP primarily via the electron transport chain (ETC), located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Electrons derived from Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NADH) and Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FADH2) are transferred through complexes I–IV, creating a proton gradient that drives ATP synthesis through complex V (ATP synthase).29,30 Disruptions in ETC function, particularly at complexes I and III, are well documented in PD and HD, leading to decreased ATP output, synaptic failure and neuronal death.31

Calcium homeostasis

Mitochondria regulate intracellular calcium (Ca2+) by rapidly sequestering it through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), especially at endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondria contact sites. This buffering stabilizes synaptic activity and prevents cytotoxic Ca2+ overload32. In neurodegenerative contexts, mitochondrial Ca2+ dysregulation can trigger opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), leading to membrane depolarization, swelling, and apoptotic or necrotic death.32

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and redox signaling

As a byproduct of electron leakage in the ETC, mitochondria generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide and hydrogen peroxide.33,34 At physiological levels, ROS act as signaling molecules, but excessive ROS can oxidize lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, contributing to oxidative stress. Elevated ROS is observed in both PD and HD and is exacerbated by toxins such as rotenone and paraquat.35 Endogenous antioxidant defenses (e.g., superoxide dismutase, glutathione) often become overwhelmed, further driving neurodegeneration.36,37

Apoptosis and mitochondria-mediated cell death

Mitochondria are key regulators of intrinsic apoptosis. Upon mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), cytochrome c is released into the cytosol, triggering activation of caspase-9 and downstream effector caspases.38 In PD and HD, pro-apoptotic proteins such as BCL2-associated X (BAX)and p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) are upregulated, while anti-apoptotic factors like B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) are downregulated, tipping the balance toward cell death. Aggregates of mutant huntingtin and α-synuclein can directly compromise mitochondrial membranes, exacerbating cell vulnerability to apoptosis.35,39

Mitochondrial dynamics: fission, fusion, and motility

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that undergo continuous cycles of fission and fusion, regulated by GTPases such as dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) (fission) and mitofusin 1/2 (MFN1/2) and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) (fusion).40,41 These processes maintain mitochondrial integrity, facilitate content exchange, and ensure distribution along axons and dendrites. In PD, hyperactivation of DRP1 and fragmentation of mitochondria are observed, while in HD, trafficking defects impair the delivery of mitochondria to synapses, disrupting local energy supply.42–44

Mitophagy and quality control

Mitophagy, the selective autophagic degradation of damaged mitochondria, is essential for mitochondrial quality control.45 It is orchestrated by the PINK1-Parkin pathway, which labels dysfunctional mitochondria for degradation.46,47 Loss-of-function mutations in PINK1 or PRKN impair mitophagy, leading to the accumulation of dysfunctional organelles, a hallmark of familial PD.48 Similarly, in HD, mutant huntingtin interferes with autophagosome formation and mitochondrial turnover, exacerbating energy deficits and oxidative stress.49

Genetic mutations and mitochondrial vulnerability in Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases

Neurodegenerative disorders such as PD and HD are increasingly understood not only through their protein-opathy-driven frameworks but also through the lens of mitochondrial vulnerability, where genetic mutations directly compromise organelle function. Advances in genomics and molecular neuroscience have revealed that several PD- and HD-associated genes converge on mitochondrial quality control, dynamics, and bioenergetics, underscoring a common mechanistic foundation (discussed in Table 1).8,50,51

Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD)

| Characteristic | PD | HD |

|---|---|---|

| Impaired mitophagy | Mutations in PINK1 and Parkin impair clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria | Mutant huntingtin (mHTT) downregulates autophagy-related genes, reducing mitophagy efficiency |

| Abnormal fission/Fusion balance | LRRK2 enhances DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation | mHTT disrupts expression of fission and fusion proteins, leading to abnormal dynamics |

| Defective axonal transport | LRRK2 interferes with the Miro–Milton complex, impairing mitochondrial trafficking | mHTT binds to motor protein complexes, disrupting axonal mitochondrial transport |

| Disruption of respiratory chain complex I | α-Synuclein aggregation inhibits complex I activity, impairing oxidative phosphorylation | mHTT reduces transcription of complex I subunits, lowering respiratory efficiency |

| Increased oxidative stress and calcium sensitivity | PINK1, Parkin, LRRK2, and α-synuclein mutations increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) and calcium sensitivity | mHTT promotes ROS production and exacerbates calcium dysregulation |

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) and Parkin: Guardians of mitophagy in PD

Mutations in PINK1 and Parkin (PRKN) are among the most well-characterized genetic causes of early-onset PD. Under physiological conditions, PINK1 is imported into healthy mitochondria and degraded. However, when mitochondrial membrane potential is lost, PINK1 accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM),52 where it recruits and activates the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin. Parkin ubiquitinates several OMM proteins (e.g., VDAC1, Mfn2), marking the organelle for selective degradation via mitophagy.53,54 In PD, loss-of-function mutations in PINK1 or Parkin impair this surveillance mechanism, leading to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, elevated ROS, and apoptotic sensitivity in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra.55 Recent cryo-EM studies have elucidated the conformational activation of Parkin by phosphorylated ubiquitin and PINK1, reinforcing the “feed-forward” loop essential for mitochondrial clearance. Additionally, mitophagy-independent roles for Parkin in mitochondrial-derived vesicle formation and redox homeostasis have emerged, expanding its functional repertoire.56

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2): Modulator of mitochondrial dynamics

LRRK2 is the most common genetic contributor to autosomal dominant PD.57,58 The G2019S mutation increases its kinase activity and alters several downstream processes, including mitochondrial fission, motility, and autophagy. LRRK2 interacts with DRP1, facilitating mitochondrial fragmentation.58,59 In parallel, mutant LRRK2 disrupts mitochondrial trafficking along axons by impairing the Miro–Milton–kinesin complex.60 Furthermore, mutant LRRK2 suppresses mitophagy by interfering with Rab GTPases-mediated vesicular transport. LRRK2 inhibitors (e.g., DNL201, BIIB122) are in clinical trials, aiming to restore mitochondrial homeostasis.59,61 In vitro studies confirm that LRRK2 kinase inhibition enhances mitophagy and preserves mitochondrial network integrity.62

α-Synuclein: A structural stressor on mitochondria

Although SNCA mutations are less common, duplications, triplications, and point mutations (e.g., A53T, E46K) in the gene encoding α-synuclein cause familial PD. Aggregated α-synuclein associates with mitochondrial membranes, particularly mitochondria-associated ER membranes, where it disrupts calcium signaling and bioenergetics.63 α-synuclein interferes with complex I activity, enhances mitochondrial fragmentation, and blocks mitophagic flux.64 Moreover, it interacts with cardiolipin in the inner mitochondrial membrane, potentially altering cristae structure and triggering cytochrome c release.65,66 Single-molecule biophysics techniques now show that α-synuclein oligomers form lipid pores in mitochondrial membranes, permitting uncontrolled ion flux and loss of membrane potential.67,68

GBA: Lysosomal–mitochondrial crosstalk in PD

Variants in the GBA gene, encoding the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase, represent one of the most prevalent genetic risk factors for PD, affecting 5–15% of patients.69,70 Loss-of-function mutations impair lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein and disrupt sphingolipid metabolism, establishing a pathological feedback loop between lysosomal stress, α-synuclein accumulation, and mitochondrial dysfunction.70,71 GBA deficiency lowers mitochondrial membrane potential and reduces complex I activity, thereby compounding bioenergetic deficits. Clinically, GBA-associated PD is often characterized by earlier onset, more rapid progression, and higher rates of cognitive decline compared to sporadic PD, highlighting lysosomal–mitochondrial crosstalk as a central pathogenic axis in PD.70,72

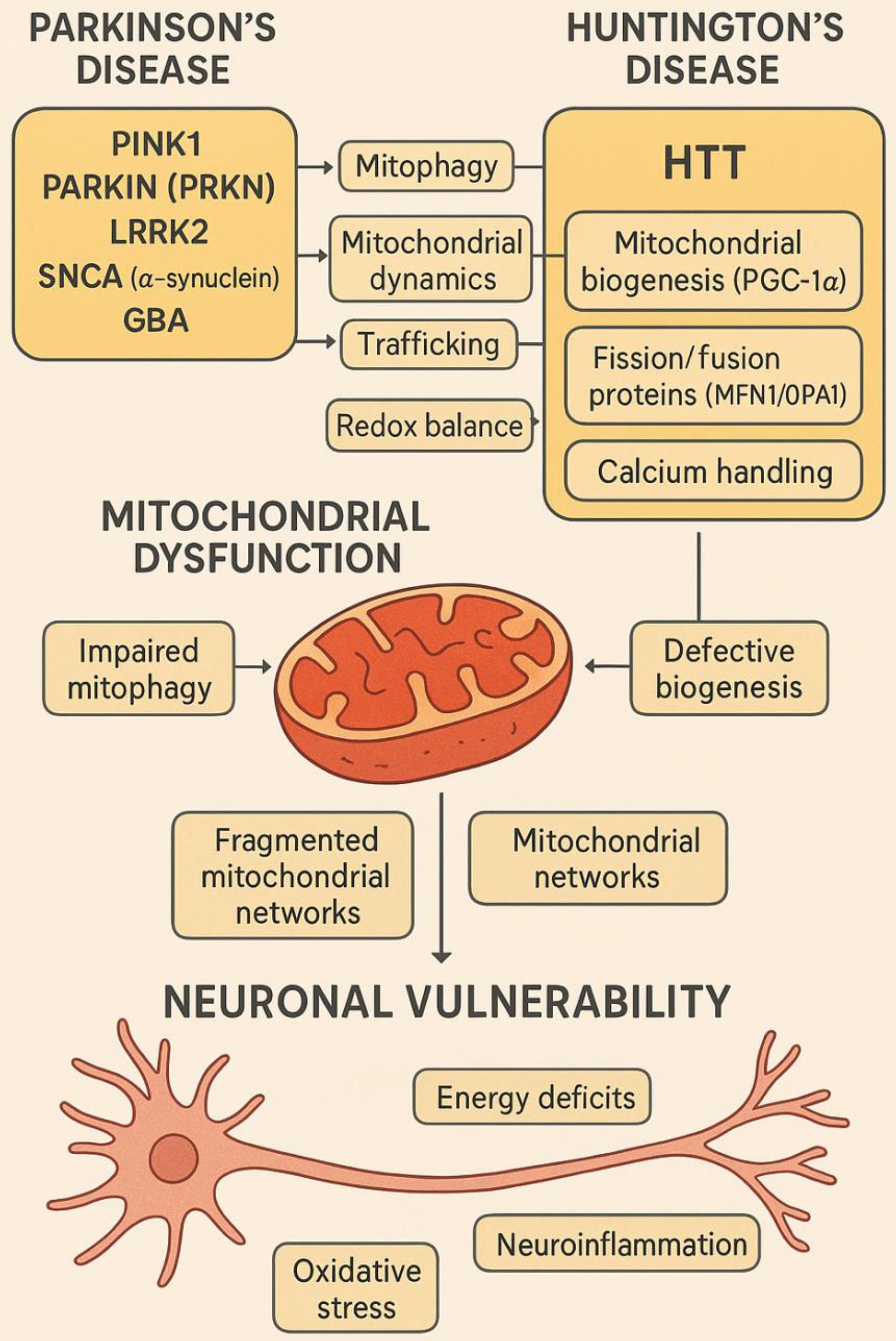

Mutant Huntingtin and mitochondrial dysregulation in HD

HD is caused by an expanded CAG repeat in the HTT gene, resulting in mutant huntingtin (mHTT) with an elongated polyglutamine (polyQ) tract.47,73 This toxic gain-of-function protein disrupts multiple cellular pathways, with mitochondria among the earliest and most severely affected organelles.74 mHTT impairs axonal mitochondrial transport, decreases the expression of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins (e.g., MFN1, OPA1), and inhibits peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis.75,76 It also binds the outer mitochondrial membrane and promotes mPTP opening, increasing vulnerability to calcium and oxidative stress. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) mediated excision of the expanded CAG tract in HD iPSC-derived neurons has been shown to restore mitochondrial respiration and dynamics, demonstrating a direct gene-organelle pathological axis (as shown in Fig. 3).77,78

GBA, glucosylceramidase beta; HTT, Huntingtin; LRRK2, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2; MFN1, mitofusin 1; OPA1, optic atrophy 1; PARKIN, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase parkin; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha; PINK1, PTEN-induced kinase 1; SNCA, synuclein alpha (α-synuclein).

This schematic illustrates how key genetic mutations associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD) converge on mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to neuronal vulnerability. In PD, mutations in PINK1, Parkin (PRKN), LRRK2, SNCA (α-synuclein), and GBA disrupt mitophagy, mitochondrial dynamics, trafficking, and redox balance. In HD, the mutant HTT protein impairs mitochondrial biogenesis by interfering with PGC-1α, alters fission/fusion dynamics (affecting MFN1/OPA1), disrupts calcium handling, and promotes mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening. These molecular perturbations lead to impaired mitophagy, defective biogenesis, calcium dyshomeostasis, and fragmented mitochondrial networks. Ultimately, the pathological consequences include energy deficits, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neuronal death, central to disease progression.1,5,79

The interplay between environmental toxins and genetic predispositions

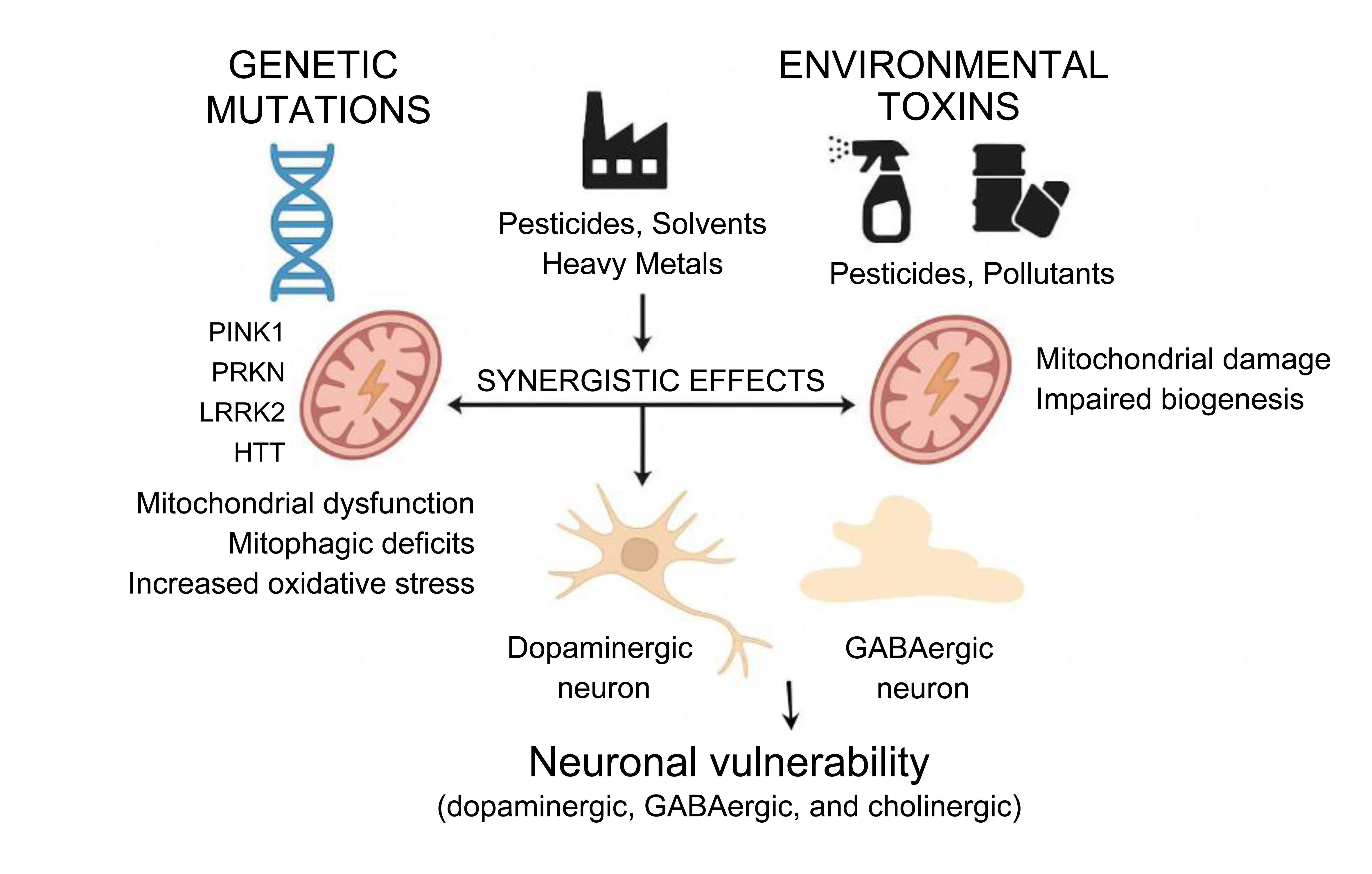

The development and progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as PD and HD reflect a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures.80,81 While monogenic mutations in genes such as PINK1, PRKN, LRRK2, and HTT establish a molecular predisposition, environmental toxins often precipitate or accelerate the clinical disease. Experimental and epidemiological studies consistently show that genetically vulnerable neurons exhibit heightened sensitivity to environmental stressors. For instance, dopaminergic neurons lacking PINK1 or Parkin exhibit exaggerated mitochondrial depolarization, mitophagy failure, and ROS accumulation upon exposure to pesticides such as rotenone or paraquat.82,83 Similarly, mutant LRRK2 (G2019S) knock-in mice display exacerbated mitochondrial fragmentation and dopaminergic cell loss when challenged with trichloroethylene, an industrial solvent linked to PD in occupational settings (Fig. 4).83–85

Genetic mutations in genes such as PINK1, PRKN, LRRK2, and HTT disrupt mitochondrial quality control by impairing mitophagy and increasing oxidative stress. Simultaneously, exposure to environmental toxins—including pesticides, solvents, heavy metals, and airborne pollutants—damages mitochondrial directly, reduces biogenesis, and drives epigenetic alterations. These two factors act synergistically to exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, leading to dopaminergic neuron damage and progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as PD and HD.84,85 GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; HD, Huntington’s disease; HTT, Huntingtin gene; PD, Parkinson’s disease. LRRK2, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2; Parkin (PRKN), E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin; PINK1, PTEN-induced putative kinase 1.

Environmental toxins not only damage mitochondria directly but also intersect with the molecular pathways already dysregulated by genetic mutations. Several pesticides and industrial compounds impair autophagic flux and lysosomal degradation, thereby exacerbating mitophagic deficits in Parkin-deficient cells.83 Heavy metals such as manganese and cadmium downregulate the transcription of mitochondrial biogenesis regulators, including PGC-1α and nuclear respiratory factor 1, both of which are already repressed in HD due to mutant huntingtin-mediated transcriptional interference.86 Furthermore, airborne particulate matter and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) can hyperactivate DRP1 to enhance mitochondrial fission, aggravating the fragmentation already driven by mutant LRRK2 or mHTT.87 These findings support a “multiple hit” hypothesis, whereby environmental stressors magnify the pathological effects of disease-associated gene variants, often pushing mitochondrial function beyond a recoverable threshold.88 A summary of the pathological effects associated with these genes is provided in Table 2.

Gene–mitochondrial dysfunction–pathology links in PD and HD

| Gene/Protein | Disease | Mitochondrial dysfunction | Pathological consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| PINK1 | PD | Impaired mitophagy due to failed mitochondrial membrane potential sensing | Accumulation of damaged mitochondria, oxidative stress, dopaminergic neuron loss |

| Parkin (PRKN) | PD | Defective ubiquitination of outer mitochondrial membrane proteins | Failure of mitochondrial clearance, increased ROS, apoptosis |

| LRRK2 | PD | Hyperactive fission, disrupted trafficking, inhibition of mitophagy | Mitochondrial fragmentation, reduced energy production, neuroinflammation |

| α-Synuclein | PD | Binds mitochondrial membranes, disrupts complex I and MAMs | Mitochondrial swelling, cristae disruption, calcium dysregulation |

| HTT (mutant huntingtin) | HD | Inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis, impairs dynamics and trafficking | Decreased ATP production, mitochondrial fragmentation, synaptic failure |

| PGC-1α | HD | Transcriptional repression of mitochondrial biogenesis regulators | Energy deficit, increased oxidative stress, neuronal degeneration |

| MFN1 / OPA1 | Both | Downregulated, impairing fusion and cristae maintenance | Fragmented mitochondria, loss of membrane potential, apoptosis |

| DRP1 | Both | Hyperactivated (especially in PD and HD models) | Excessive fission, mitochondrial fragmentation, neurodegeneration |

Beyond direct molecular interactions, environmental toxins may modulate the expression of mitochondrial genes through epigenetic alterations.89 For example, chronic exposure to pollutants like dieldrin and benzo[a]pyrene activates histone deacetylases, suppressing the transcription of antioxidant enzymes and mitochondrial transcription factors.90 In brain samples from PD patients with known toxin exposure, DNA methylation of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes such as TFAM and MFN2 has been observed, further implicating epigenetic remodeling in disease pathogenesis. These modifications may establish persistent mitochondrial defects that remain even after exposure ends, creating a latent risk for neurodegeneration.91 The intersection between gene mutations and environmental insults is crucial for developing personalized therapeutic approaches. Patients harboring mutations in mitophagy-related genes may benefit from treatments that enhance lysosomal degradation or support mitochondrial biogenesis.92 Nrf2 pathway activators such as sulforaphane or dimethyl fumarate have shown promise in restoring redox homeostasis and enhancing mitochondrial resilience in toxin-exposed, genetically predisposed neurons. Small-molecule inhibitors of DRP1, such as Mdivi-1, are under investigation for their potential to reverse mitochondrial fragmentation induced by both genetic mutations and environmental factors.93 These insights reinforce the need for precision medicine approaches that consider a patient’s genetic profile and environmental exposure history.

As shown in Table 3, quantitative data from epidemiological and experimental studies reinforce the strong link between environmental toxins and neurodegenerative risk. For instance, agricultural workers with long-term exposure to paraquat or rotenone exhibit a 2–3-fold increase in PD incidence. This is consistent with rodent models in which low-dose, chronic administration reproduces nigrostriatal degeneration and α-synuclein aggregation.94,95 Similarly, industrial exposure to trichloroethylene is associated with a markedly elevated PD risk, a finding mirrored in murine studies showing mitochondrial fragmentation and dopaminergic loss at doses of 200–400 mg/kg/day.96,97 Heavy metals such as manganese and cadmium show clear dose-dependent neurotoxicity in both humans and animal models, with elevated blood or urinary levels correlating with impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and motor dysfunction.87,98 Chronic airborne pollutants, particularly PM2.5 and PAHs, also present a significant epidemiological risk, linked to increased PD incidence and mitochondrial gene methylation changes.99,100 Collectively, these quantitative findings support a dose–response relationship in which even moderate, sustained exposure can synergize with genetic predispositions to drive neurodegenerative pathology.

Quantitative evidence linking environmental toxins to neurodegenerative disease risk

| Toxin / Pollutant | Typical exposure levels | Epidemiological data (human) | Experimental dose–response (model systems) | Key Pathological outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraquat (herbicide) | Agricultural workers: >20 days/year use | 2–3× higher PD risk vs non-exposed | Rodents: 10 mg/kg i.p. twice weekly → progressive dopaminergic neuron loss | Oxidative stress, mitochondrial depolarization, α-synuclein aggregation |

| Rotenone (pesticide) | Farm workers, chronic occupational contact | ∼70% ↑ PD incidence in exposed individuals | 2–3 mg/kg/day oral/rodent → PD-like motor deficits | Complex I inhibition, ROS generation, nigrostriatal degeneration |

| Trichloroethylene (TCE, solvent) | Industrial settings: ≥25 ppm for >5 years | 6× higher PD risk among exposed workers | 200–400 mg/kg/day in mice → mitochondrial dysfunction & α-syn aggregation | Mitochondrial fragmentation, dopaminergic cell loss |

| Manganese (Mn, welding fumes) | Blood Mn >10 µg/L in welders | Elevated PD-like symptoms & motor deficits | Rodents: 15–50 mg/kg MnCl2 → impaired motor function | Inhibition of mitochondrial biogenesis, basal ganglia accumulation |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Urinary Cd >1 µg/g creatinine | Associated with cognitive decline & PD-like motor impairment | Chronic exposure in rodents (1–5 mg/kg) → mitochondrial DNA damage | Suppression of PGC-1α, NRF1, oxidative stress |

| Air pollution (PM2.5, PAHs) | Urban PM2.5 >12 µg/m3; PAHs ∼10–20 ng/m3 roadside | 1.2–1.5× ↑ PD risk with chronic PM exposure | Long-term inhalation in mice → neuroinflammation & α-syn upregulation | Epigenetic changes (DNA methylation of TFAM, MFN2), enhanced DRP1-mediated fission |

Beyond mitochondrial impairment, environmental toxins disrupt other cellular systems that contribute to neurodegeneration. Several pesticides and heavy metals can induce ER stress, triggering the unfolded protein response and perturbing calcium homeostasis, which further sensitizes neurons to apoptotic signaling.101 Toxins such as dieldrin have been shown to impair lysosomal function and autophagic flux, exacerbating mitophagy deficits already present in PINK1- and Parkin-mutant backgrounds. Chronic exposure to airborne pollutants (PM2.5, PAHs) and manganese also activates microglial inflammatory cascades, leading to sustained release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-1 Beta (IL-1β)) and reactive oxygen species.102,103 This neuroinflammatory milieu not only damages neurons directly but also amplifies ER and mitochondrial stress, establishing a vicious cycle of cellular dysfunction.104 These findings underscore that the pathogenic synergy between genetic predisposition and environmental exposure extends beyond mitochondria to include ER stress responses, lysosomal degradation pathways, and neuroinflammatory signaling. Together, these interconnected dysfunctions accelerate the progression of PD and HD.

Therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial dysfunction in PD and HD

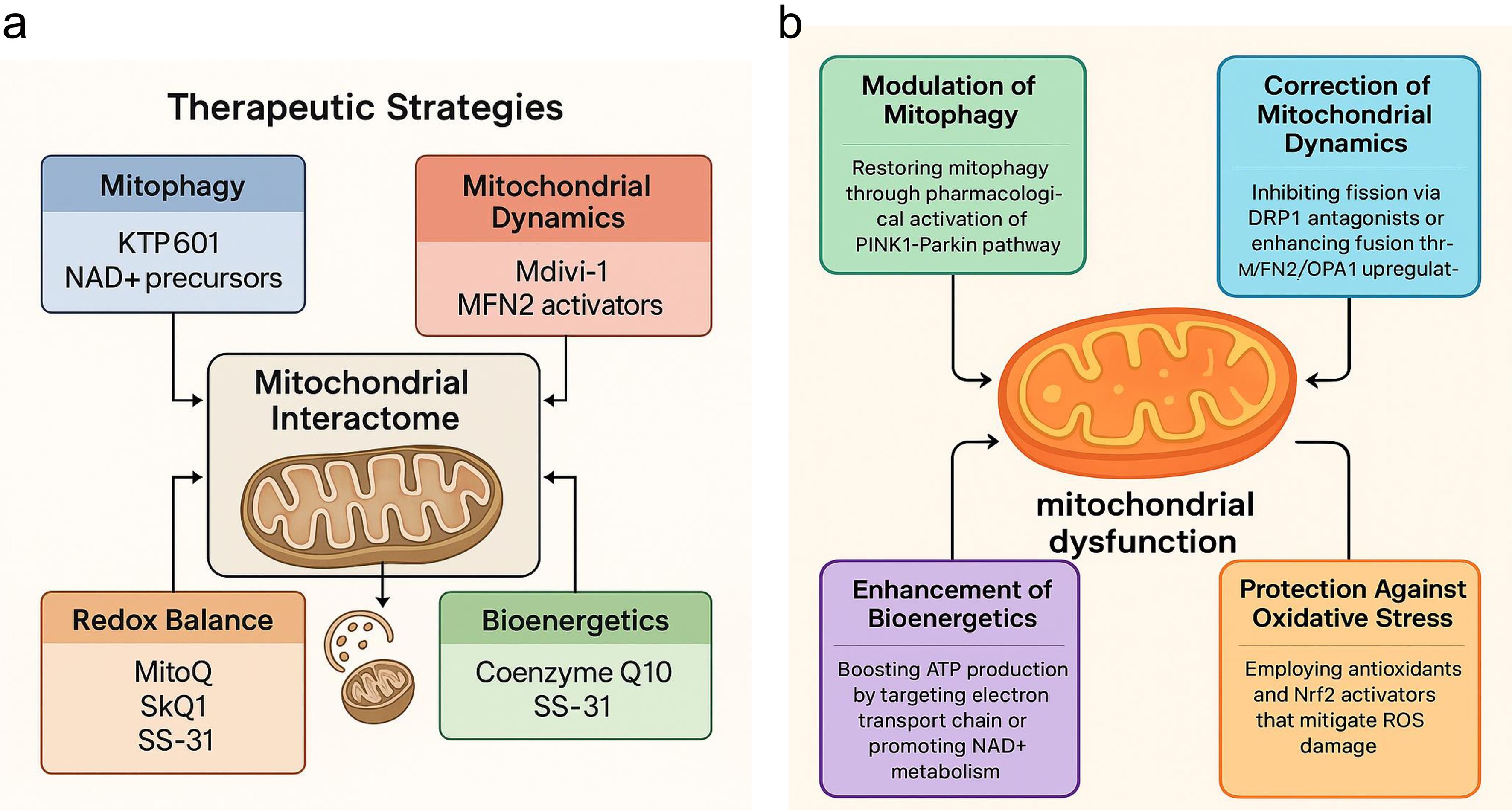

Given the central role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of both PD and HD, mitochondria have emerged as critical therapeutic targets (Fig. 5a, b).105 Unlike traditional symptomatic treatments, which primarily modulate neurotransmitter levels, mitochondrial-targeted therapies aim to reverse or mitigate upstream cellular pathology, offering the potential for disease modification.106 A key therapeutic strategy involves restoring mitophagy—the selective autophagic degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria—which is compromised in PD due to mutations in PINK1 and Parkin, and in HD due to mHTT-mediated inhibition of autophagic flux.107 Several pharmacological agents are being developed to enhance PINK1-Parkin signaling or bypass defective steps.108 For instance, small molecules such as KTP601 can stabilize PINK1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane, while others mimic phosphorylated ubiquitin to activate Parkin. AMP-activated protein kinase activators like metformin and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) have been shown to stimulate both mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis in preclinical PD models, even with impaired PINK1-Parkin signaling. Despite strong preclinical data, translating these findings has proven challenging. Mitophagy enhancers and metabolic modulators often face significant hurdles, such as poor pharmacokinetics, uncertain dosing regimens, and variable target engagement in human neurons, which have limited their clinical advancement.109–111 Another therapeutic axis involves modulating mitochondrial dynamics—specifically, correcting the imbalance between fission and fusion.112 Excessive fission, common in both PD and HD, contributes to bioenergetic decline and pro-apoptotic signaling. Pharmacological inhibitors of DRP1, such as Mdivi-1, can reduce mitochondrial fragmentation and preserve neuronal viability.113 In HD models, enhancing the expression of fusion-promoting proteins like MFN2 and OPA1 through gene therapy or small molecules has shown promise in restoring mitochondrial morphology and improving ATP production.114 However, Mdivi-1 and related DRP1 inhibitors have not progressed to human trials due to off-target effects and safety concerns, underlining the difficulties in developing safe modulators of mitochondrial dynamics.115,116 At the genetic level, CRISPR/Cas9 technologies are being employed to correct the pathogenic HTT expansions or to knock down hyperactive mutant LRRK2 alleles. These approaches have successfully restored mitochondrial respiration and dynamics in patient-derived iPSC models, presenting a promising avenue for precision therapeutics.117

Figure created using Biorender and Napkin AI. (a) Therapeutic Strategies: Emerging mitochondria-targeted interventions address these pathological mechanisms. Approaches include restoring mitophagy (KTP601, NAD+ precursors), modulating mitochondrial dynamics (Mdivi-1, MFN2 activators), enhancing redox balance (MitoQ, SkQ1, SS-31), and improving bioenergetics (Coenzyme Q10, SS-31). Together, these strategies highlight mitochondria as a central therapeutic target in neurodegenerative disease modification. (b) Pathophysiological Basis: Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to neuronal vulnerability in PD and HD through several interconnected pathways: impaired mitophagy, altered dynamics, redox imbalance, and compromised bioenergetics. These disruptions amplify oxidative stress, energy failure, and progressive neurodegeneration. ATP, adenosine triphosphate; HD, Huntington’s disease; MFN2, mitofusin 2; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized form); OPA1, optic atrophy 1; PD, Parkinson’s disease; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Improving mitochondrial bioenergetics remains a cornerstone of therapeutic development. Agents such as coenzyme Q10 and creatine, though showing mixed results in large-scale trials, have demonstrated the ability to enhance electron transport chain activity and buffer ATP levels in early-stage PD and HD, as shown in Figure 5a.118 More recently, targeting NAD+ metabolism with compounds like nicotinamide riboside and nicotinamide mononucleotide has gained attention. These compounds boost sirtuin activity and PGC-1α-mediated biogenesis, thereby enhancing mitochondrial resilience to oxidative and metabolic stress. However, translating these strategies has proven challenging. Large-scale clinical trials of coenzyme Q10 and creatine in PD and HD yielded disappointing results, showing no significant disease-modifying benefits despite strong biochemical rationale and early pilot data. These failures highlight challenges related to brain penetrance, trial design, and the possibility that mitochondrial rescue may only be effective during specific disease stages or in particular genetic subgroups.119–122 Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants represent another promising avenue.123 Unlike conventional antioxidants, compounds such as MitoQ, SkQ1, and SS-31 are designed to accumulate within mitochondria, where they neutralize ROS at the source and stabilize mitochondrial membranes. These molecules have shown promise in reducing lipid peroxidation and preserving mitochondrial potential in animal models and are currently undergoing clinical evaluation.119,124,125 Parallel strategies involve activating Nrf2 pathway—a master regulator of antioxidant and detoxification responses. Nrf2 activators like dimethyl fumarate upregulate cellular defenses and improve mitochondrial morphology and function in both PD and HD models. While early-phase trials are ongoing, their long-term efficacy and safety remain uncertain. These translational gaps underscore the need for precision medicine approaches, integrating patient-derived iPSCs, multi-omics biomarkers, and advanced imaging to identify patients most likely to benefit from mitochondria-targeted therapies.25,126

Cutting-edge approaches such as mitochondrial transplantation and nanomedicine represent the next frontier. Mitochondrial transplantation involves the direct transfer of healthy mitochondria into damaged neurons, a strategy that has shown neuroprotective effects in rodent models of PD.127 Complementarily, nanocarrier systems, including liposomes and cerium oxide nanoparticles, are being engineered to deliver antioxidants, gene-editing tools, or even intact mitochondria across the blood–brain barrier. While challenges remain concerning immune compatibility, targeted delivery, and long-term integration, these novel platforms underscore a future in which mitochondria-centric interventions may transform the therapeutic landscape of neurodegenerative diseases.117

Limitations and future directions

Despite significant advances, important gaps remain in understanding the mitochondrial interactome in neurodegeneration. Mechanistic connections between specific gene mutations (e.g., PINK1, PRKN, LRRK2, GBA, and HTT) and mitochondrial dysfunction are still incompletely mapped, particularly across different neuronal subtypes. Human data on long-term epigenetic consequences of environmental exposures are scarce, and standardized biomarkers for mitochondrial dysfunction are lacking, hindering both early diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring. Furthermore, most evidence derives from PD and HD models, which may not fully represent mitochondrial dynamics in other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease or ALS. Future research should focus on (i) patient-derived iPSC models and advanced imaging modalities to capture disease heterogeneity, (ii) multi-omics approaches to discover reliable, clinically translatable mitochondrial biomarkers, (iii) integrative studies that assess the combined impact of genetics, environment, and organelle cross-talk (ER stress, lysosomal impairment, neuroinflammation), and (iv) translational efforts to improve brain penetrance and specificity of mitochondria-targeted therapeutics. Collaborative, cross-disease studies will be crucial to validate the mitochondrial interactome as a unifying framework and accelerate the development of precision therapies.

Conclusions

This review positions mitochondria at the center of PD and HD pathogenesis, where genetic mutations and environmental exposures converge to disrupt cellular homeostasis. By mapping the mitochondrial interactome, we identify actionable therapeutic nodes, including impaired mitophagy, fission–fusion imbalance, and oxidative stress, that represent actionable therapeutic nodes. Promising strategies that move beyond symptomatic management include mitochondria-targeted antioxidants (e.g., MitoQ, SS-31), DRP1 inhibitors (e.g., Mdivi-1), NAD+ boosters (e.g., nicotinamide riboside, nicotinamide mononucleotide), and gene-editing techniques for mutations in genes such as LRRK2 and HTT. Combining these approaches with precision medicine tools—such as iPSC-based modeling, advanced imaging, and biomarker-guided patient stratification—will be essential to overcome translational barriers. Mitochondria represent not only a shared vulnerability in PD and HD but also a promising focal point for therapeutic development. Harnessing mechanistic insights into the mitochondrial interactome can pave the way for individualized, mitochondria-centered interventions with the potential to alter disease progression and improve patient outcomes.

Declarations

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design (HG, YB), acquisition of data (HG), analysis and interpretation of data (HG, YB), drafting of the manuscript (HG), critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (HG, YB, VM), framing and refinement of specific sections (VM), visualization including design and preparation of figures (HG, YB), and study supervision (YB, VM). All authors have made significant contributions to this work and have approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Author information