Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). While the exact cause of IBD remains uncertain, current scientific evidence suggests that an abnormal immune response to the microbiota in the intestinal tract is a primary contributing factor.1 Regulatory T (Treg) cells and T helper (Th) 17 cells are two T cell sub sets implicated in the pathophysiology of IBD. Th1 cells are essential for removing intracellular pathogens, while Th2 cells mediate allergic reactions and provide protection against parasites. Patients with IBD have more Th17 cells in the lamina propria. Tregs also play a significant role in maintaining intestinal mucosal homeostasis by suppressing aberrant immune responses to dietary antigens or symbiotic flora. Research has indicated that adaptive immunity mostly affects Th1)/Th2 and Th17/Treg ratios.2,3

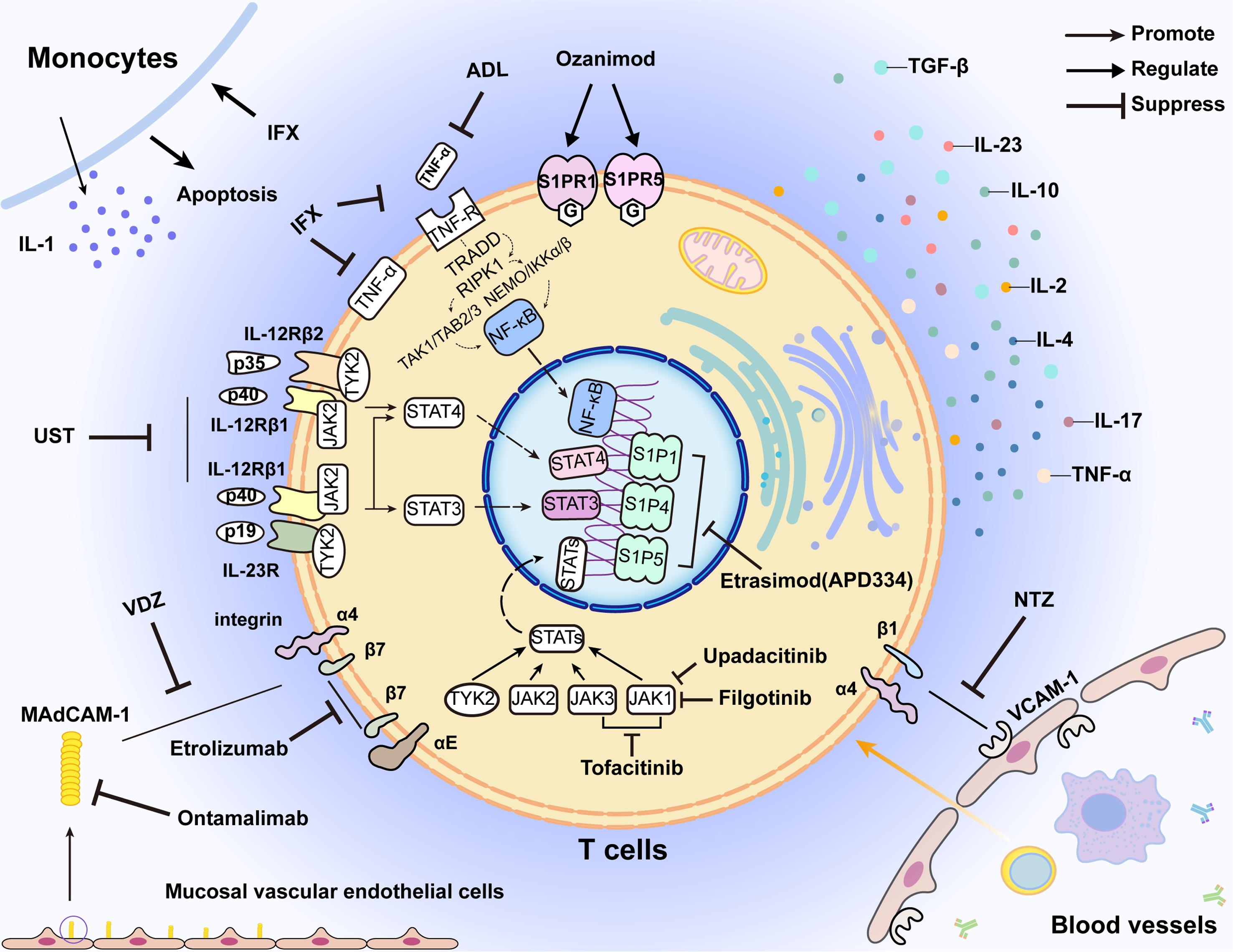

The effects of biological agents (BAs) on immune balance and their effectiveness in treating IBD are still not fully understood. Emerging inhibitors targeting cytokines, integrins, cytokine signaling pathways, and cell signaling receptors have shown promise as preferred treatment modalities for many IBD patients. While conventional therapies such as 5-aminosalicylic acid, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anti-tumor necrosis factor agents continue to be effective, especially in combination with other drugs, the field is evolving towards more targeted and efficient treatment options. This review consolidates findings from chemical, biological, and adjunct therapies to assess current and future IBD treatments, elucidating the mechanisms of action for each therapy and highlighting potential avenues for further development.

Th1/Th2

Levels of IFNc and interleukin (IL) 12 demonstrate an inverse correlation with platelet counts, similar to the Th1/Th2 ratio. The imbalance between Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg, potentially triggered by the distinction between plasmacytoid dendritic cells/myeloid dendritic cells, and elevated levels of IL6, IL12, and IL23, leads to the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into Th1 and Th17 cells, ultimately resulting in increased Th1 and Th17 production. IL6 plays a crucial role in regulating the equilibrium between Th17 and Treg cells. IL6, together with transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), induces the differentiation of Th17 cells from T cells while inhibiting the differentiation of Treg cells induced by TGF-β. In addition, dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages mainly express IL6 and IL23, which promote the differentiation of Th0 cells into Th17 cells.4 DC subsets primarily influence the differentiation of Th0, Th1/Th2 cell ratio, and Th17/Treg ratio by cytokine release, quantity variation, subpopulation proportion imbalance, and maturation. Hence, an imbalance in the ratio of DC subsets may be a key mechanism contributing to this imbalance.4 Based on this premise, biologics that alter the Th1/Th2 ratio will be discussed below.

TNF-α antagonists

In individuals with IBD, there is excessive production of TNF-α by lamina propria cells. This pro-inflammatory mediator can promote the adherence of white blood cells to vascular endothelial cells and their recruitment to the affected site, potentially influenced by abnormal interactions between the host and intestinal flora.5 The mechanism by which anti-TNF-α drugs induce the production of autoantibodies is the subject of numerous theories. These include: (1) the inflammatory cells may undergo apoptosis due to an imbalance between TNF-α and interferon-α; (2) the production of DNA and other nuclear targets is facilitated by the agglomeration of macrophages and the nucleosomes of arrested cells; and (3) the activation of lymphocytes leads to the production of polyclonal B lymphocytes. Anti-TNF-α antibodies can block the binding of soluble TNF-α to the surface of activated T lymphocytes, thereby altering the Th1/Th2 ratio.

Currently, three anti-TNF-α antibodies are used in the treatment of UC patients: infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADL), which primarily exert anti-inflammatory effects by targeting and inhibiting TNF-α.6 IFX is an anti-TNF-α chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody composed of a human constant region and a mouse variable region. Apart from its ability to neutralize TNF-α, IFX can also cause T cells and monocytes to undergo apoptosis and inhibit leukocyte migration.7 ADL is a transgenic anti-TNF antibody that is manufactured from animals and specifically binds to TNF-α. It controls the inflammatory response by associating with the TNF cell receptor on the cell membrane to block the signal transduction mechanism that activates inflammation.7

Anti-IL12 and anti-IL23 agents

Antigen-presenting cells secrete cytokines IL12 and IL23 upon innate signals. The binding of these cytokines to their receptors triggers TYK2 and JAK2 activation within immune cells, initiating JAK/STAT signaling. TYK2 mediates downstream signaling of IL12, IL23, and type I interferon receptors on immune cells, promoting STAT phosphorylation. JAK2 is associated with hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors, and JAK2 mutations occur in myeloid cells derived from CD34+ cells. Generation and activation of TYK2 and JAK2 are influenced by cytokines and cell types, potentially playing roles in various cells under physiological or pathological conditions.

The JAK/STAT signaling pathway involves phosphorylation of STAT4 in response to IL12 and IL23. Phosphorylated STAT4 dimers regulate inflammatory and immune genes in the nucleus.8,9 Monoclonal antibodies targeting the shared p40 subunit of IL12 and IL23, including ustekinumab and briakinumab,10 are developed to treat immune-mediated diseases. These antibodies modulate the JAK/STAT pathway by blocking cytokine-receptor interactions, reducing inflammation. Their effectiveness lies in regulating immune cell activation and proliferation through the JAK/STAT pathway.

Anti-integrin antibodies

Integrins are cell surface glycoprotein receptors capable of bidirectional signal transduction and can interact with adhesion molecules to facilitate the migration of white blood cells into surrounding tissues.11 Among them, α4β7 integrins are exclusively expressed on the surface of intestine-specific lymphocytes and play a crucial role in mediating the migration of inflammatory cells to the intestinal mucosa through binding with MAdCAM1, thereby contributing to the initiation of inflammatory reactions.12 Anti-integrin antibodies, a type of biologics, selectively inhibit the binding of integrins to ligands on the surface of intestinal immune cells and endothelial cell adhesion molecules.13 This inhibition effectively hinders the migration of inflammatory cells to intestinal vessels. Furthermore, anti-integrin antibodies not only attenuate the intestinal inflammatory response but also do not compromise the overall immune function of the body, resulting in fewer adverse reactions and a stable therapeutic effect.14,15

Vedolizumab (VDZ), a representative anti-integrin antibody, has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of IBD.14 It selectively inhibits the migration of Th17 cells expressing IL17 to the lesions of ascending colonic ulcers in Crohn’s disease by specifically antagonizing α4β7 integrin, while exhibiting no affinity for α4β1 integrin. This action effectively blocks the binding of activated α4β7 integrin to its ligand MAdCAM1.16 VDZ also prevents T lymphocytes from migrating to the inflamed regions within the intestines and exerts selective suppression of gut inflammation.15,16

Furthermore, novel anti-integrin antibody drugs are in intensive development. Natalizumab)effectively targets α4β1 and α4β7 and selectively blocks inflammatory cell migration by inhibiting integrin α4 signaling. Etrolizumab specifically targets the β7 subunits of α4β7 and αEβ7 integrins, thereby preventing their involvement in the development of ulcerative colitis.17 The efficacy of induction maintenance therapy remains uncertain. Ontamalimab exerts its action by specifically binding to and inhibiting the activity of MAdCAM1, a crucial molecule involved in endothelial adhesion and lymphocyte migration to the site of inflammation in IBD.18

The therapeutic effect of anti-integrin antibodies plays a significant role in clinical remission rates, reflectivity, and mucosal healing rate, which has a stronger safety margin and deserves an in-depth analysis and study.

JAK inhibitor

sJAK inhibitors, including TYK2, JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3, are intracellular non-receptor tyrosine kinases.19 Upon cytokine receptor-ligand binding, these paired JAK proteins undergo activation and form STAT dimers. Phosphorylated STAT dimers then translocate to the nucleus where they modulate the transcription of target genes.20 This signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in mediating the inflammatory response in IBD, contributing to both physiological and pathological processes.21,22 JAK1 is a pivotal therapeutic target for IBD due to its involvement in the signaling of various cytokines, including IL6, interferons, IL2, IL15, and the gamma chain of cytokine signaling.23 Inhibition of JAK1 effectively abrogates the initiation of inflammatory cascades.24 The proinflammatory cytokine GM-CSF utilizes the JAK2 signaling pathway, thus inhibition of both JAK1 and JAK2 results in a heightened anti-inflammatory response.

Tofacitinib, the pioneering oral small-molecule kinase inhibitor to undergo clinical trials, demonstrates high selectivity for human protein kinases and is categorized as a first-generation non-specific JAK inhibitor. Preclinical studies have validated its potent inhibition of JAK1/JAK3, which holds promise in treating IBD by obstructing cytokine signal transduction activities linked to lymphocyte activation, proliferation, and function, thereby impeding both adaptive and innate immune responses.25 Filgotinib represents the second generation of JAK inhibitors with specific targeting of JAK1.26,27 Filgotinib is a second-generation of JAK inhibitor that can selectively inhibit JAK1.28 Despite its limited inhibitory effect on cytokine receptors as a selective JAK inhibitor, it can exert various anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing IL2, IL6, interferon-γ, and other signaling pathways.21

Currently, the use of selective JAK inhibitors is emerging as a new research trend; however, there is a lack of direct comparative data from clinical trials, and further exploration is needed to determine whether their application results in improved efficacy and safety.

Others

The participation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors (S1PRs) in cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation is orchestrated by its diverse receptor subtypes, each accountable for discrete functions.29 The S1PR1 is extensively expressed on immune cells and exerts significant control over the movement of lymphocytes.30 Its agonist activity effectively hinders lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes, thereby impeding their migration to inflammatory sites.31

By binding to S1PRs, Gilenya facilitates the migration of lymphocytes back to lymphoid tissues and diminishes lymphocyte infiltration in the central nervous system.32,33 Ozanimod is a potent selective modulator of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptors, exhibiting high affinity for S1P receptor subtypes 1 and 5. This interaction results in the internalization of lymphocyte S1P type 1 receptors, thereby impeding the mobilization of lymphocytes to sites of inflammation.34 Etrasimod (APD334), an orally administered medication, specifically targets the S1P1, S1P4, and S1P5 signaling pathways as a modulator of S1P receptors.35 Fingolimod, Amiselimod, and Laquinimod are S1P receptor modulators, among which Laquinimod has been found to be effective and well tolerated in the treatment of CD.36 However, the exploration of new treatment directions is still insufficient, and more research is needed for drugs treating CD and UC.

The above mentioned biologic agents and their immune responses have been summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.16,25,34,37–46

Mechanisms of biologics targeting IBD

| Types of biological agents | Name of biological agents | Pharmacological targets | Effects associated with immune balance in IBD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-TNF-α preparations | Infliximab (IFX) | Targeted inhibition of TNF-α to play an anti-inflammatory role37 | Specifically binding to TNF-α→neutralizing inflammatory cells or inducing apoptosis→forming regulatory macrophages and other mechanisms→inhibiting the induced immune response→inducing and maintaining disease remission |

| Adalimumab (ADL) | It binds specifically to TNF-α with high affinity and regulates the inflammatory response by blocking the signal transduction process that causes the inflammatory response38 | ||

| Anti-IL12/IL23 complex | Ustekinumab | Inhibition of the p40 subunit common to both IL23 and IL12 acts39 | IL12 and IL23 bind to receptors→induce naive CD4+T cells to differentiate into Th1 and Th17 cells→produce interferon-γ, IL17 and tumor necrosis factor and other inflammatory factors→Biological agents target the P40 subunit of IL12 and IL23→The above mechanisms are inhibited and promote the relief of inflammation |

| Anti-integrin | Vedolizumab | Blocking the binding of activated α4β7 integrin to its ligand MAdCAM1 prevents T lymphocytes from migrating to the inflammatory area of the intestinal tract and selectively inhibits the intestinal inflammatory response16,40 | Specifically blocking α4β7 integrin binding to the gastrointestinal vascular cell adhesion molecule MAdCAM1, or targeting inflammatory factors→inhibiting the aggregation of inflammatory cells to the intestine→reducing the intestinal inflammatory response, has intestinal selectivity |

| Natalizumab (NTZ) | Blocking integrin α4 signaling to selectively block inflammatory cell migration41 | ||

| Etrolizumab | Selectively targets the β7 subunit of α4β7 and αEβ7 integrins to prevent their involvement in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis42 | ||

| Ontamalimab | Binds MAdCAM1 and prevents adhesion to integrins on lymphocytes, thereby reducing the migration of lymphocytes to the gut43 | ||

| JAK Inhibitors | Tofacitinib | Blocking the signaling activities of cytokines related to lymphocyte activation, proliferation, and function have potential inhibitory effects on adaptive and innate immunity25 | Inhibitor activation changes the activity of immune cells and reduces the immune response→blocks the signal transduction of a variety of cytokines related to inflammatory activation→reduces the inflammatory response |

| Figotinib | It can selectively inhibit JAK1 and inhibit IL2, IL6, interferon-γ, and other signaling pathways to play a variety of anti-inflammatory effects44 | ||

| Upadacitinib | It selectively inhibits JAK145 | ||

| S1P receptor modulators | Ozanimod | It has a high binding affinity to S1P receptor subtypes 1 and 5, which allows lymphocyte S1P type 1 receptor internalization and prevents lymphocyte mobilization to inflammatory sites34 | Targeting S1P1-S1P5 receptors→affecting extracellular activation and participating in a large number of physiological and pathophysiological processes→inhibiting the discharge of lymphocytes from lymph nodes to prevent the movement of lymphocytes to inflammatory sites |

| Etrasimod (APD334) | Selective targeting of S1P1, S1P4, and S1P5 signaling pathways46 |

IFX, infliximab; ADL, adalimumab; UST, ustekinumab; VDZ, vedolizumab; S1PR, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor; TNF-R, tumor necrosis factor receptor; NTZ, natalizumab; TGF-β, transforming growth factor bata; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; MAdCAM-1, mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1; JAK, janus kinase; TYK, tyrosine kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; IL, interleukin; TRADD, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated death domain protein; RIPK1, receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1; TAK1, transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1; TAB, TAK1-binding protein; NEMO, NF-κB essential modulator; IKK, inhibitor of NF-κB kinase.

IFX neutralizes TNF-α to limit T cell expansion, inhibit leukocyte migration, and induceapoptosis in monocytes and T lymphocytes via complement activation, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and caspase signaling pathways. ADL specifically binds to soluble human TNF-α, blocking its interaction with TNF receptors and effectively suppressing the inflammatory effects of TNF-α. Ustekinumab inhibits the common subunit p40 of IL23 and IL12, thereby interfering with Th1/Th17 differentiation and the release of inflammatory factors. Anti-integrin antibodies prevent the binding between activated integrins and adhesion molecules, preventing T lymphocytes from migrating to the regions affected by enteritis. JAK inhibitors reduce the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines downstream by blocking the JAK-STAT pathways. Ozanimod binds to S1P receptors type 1 and type 5, while Etrasimod (APD334) selectively targets S1P1, S1P4, and S1P5 signaling pathways to prevent lymphocytes from migrating to sites of inflammation.

Th17/Treg

A subpopulation of CD4+ effector T lymphocytes known as Th17 cells can exacerbate the intestinal inflammatory response while protecting the intestinal mucosa by preserving the equilibrium of the immune milieu and releasing proinflammatory cytokines like IL17, IL23, and IL21. Forkhead box P3-expressing Treg cells are essential for regulating the immune response and preserving immunological homeostasis. Treg cells that specifically express Forkhead box P3 play a crucial role in suppressing the immune response and maintaining immune homeostasis. It is important to note that Tregs are not a homogeneous population and can be further classified based on their origin and function. Nevertheless, inducible Treg cells are Tregs created in vitro from naive T lymphocytes in the presence of IL2 and transforming TGF-β. In the presence of IL6, IL23, and TGF-β, CD4+ naive T lymphocytes differentiate into Th17 cells, which are activated by phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (p-STAT3) and release a large number of proinflammatory cytokines. CD4+ naive T lymphocytes differentiate into Th17 cells in the presence of IL6, IL23, and TGF-β. Increasing evidence shows that inhibition of p-STAT3 hasananti-inflammatory effect and can reduce the proliferation of Th17 cells. Moreover,p-STAT3 inhibitors promote Treg cell proliferation to improve experimental autoimmune diseases.47

Many studies have found that the dynamic balance of Th17 and Treg cells is a key factor in many inflammatory or autoimmune diseases. The imbalance of Th17and Treg cells promotes the occurrence and development of IBD, andrestoring theTh17/Treg balance usually contributes to the treatment of IBD.48,49 Some studies have found that this imbalance may be one of the mechanisms of IBD. Other research has shown that thatrestoringthe balance of Th17/Treg through drug treatment can reduce IBD inflammation levels, providing new avenues for drug therapy in IBD.47,49,50,51–56

TNF-α antagonists

The body’s normal level of TNF-α plays a crucial role in resisting bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections, promoting tissue repair, inducing tumor cell apoptosis, and performing other vital functions. However, excessive production and release of TNF-αcan disrupt the body’s immune balance, leading to various diseases including IBD under the influence of other inflammatory factors. Anti-TNF therapy has been a crucial factor in the treatment of IBD. Previous studies have found that TL1A and its functional receptor DR3 are members of the TNF/TNFR protein superfamily. The interaction between TL1A and DR3 can impact the differentiation of Th17 cells, promote Treg cell proliferation, or inhibit their function. This, in turn, regulates the balance between Th17 and Treg cells, ultimately affecting the local immune response.57 At present, the effect of anti-TNF-α agents on Th17/Treg balance is rarely mentioned in research and efficacy evaluation, and whether it can effectively impact this balance remains to be studied.

Anti-IL12 and anti-IL23 agents

IL12 and IL23, which share a common p40 subunit, are abundantly produced in IBD and play important roles in promoting and/or maintaining proinflammatory cytokine responses in these diseases. IL12 mainly targets T cells and innate lymphoid cells, promoting Th1 cell polarization and the production of interferon-X03b3 and IL21 by activating Stat4. IL23 activates Stat3 to promote the proliferation of Th17 cells. Among the anti-IL12/23 antibodies currently used for the treatment of IBD, ustekinumab blocks the downstream Th17 effector pathway by binding to the common subunit p40 of IL12/23, thereby inhibiting Th17differentiationandthe inflammatory response, demonstrating good therapeutic effects.58–60

Anti-integrin antibodies

Integrin α4/β7 on circulating lymphocytes is thetarget of the humanized antibody vedolizumab for the treatment of IBD.Lymphocytes expressingα4/β7respond strongly to cytokines IL6, IL7, and IL21, which exert typical pro-inflammatory effects. Conversely, these lymphocytes showa weaker response toIL2, which supports Treg lymphocytes. Despite the observation that integrin α4/β7+ CD4+ T lymphocytes were rare among cells expressing the Th2 marker CRTh2, their numbers increased among cells carrying the circulating T follicular helper cell marker CXCR5.Consequently, this anti-integrin treatment may impact the mucosal immune system more qualitatively and optionally substitutes pro-inflammatory effector cells to promote mucosal immune tolerance without depleting lymphocytes in the intestinal mucosa.61

Vedolizumab completely blocks effector T lymphocyte trafficking while allowing residual homing of potent Treg lymphocytes during the optimal “therapeutic window” based on the level of exposure to the target.62 In another study, colon Th17 lymphocytes from vedolizumab non-responders interacted more with classical monocytes compared to responders, while colon Th17 lymphocytes from responders interacted more strongly with myeloid dendritic cells. The proportion of Th17 cells decreased in UC patients who responded to vedolizumab.63 These findings reflect how anti-integrin antibodies influence the regulation of both the number and proportion of Th17 and Treg cells.

JAK inhibitors

JAK inhibitors, a class of BAs currently being researched and applied for the treatment of IBD, target the JAK (Janus kinase) signaling pathway for immune-related disorders. These inhibitors provide more precise targeting and a better balance of the immune response compared to traditional immunosuppressive agents.50 By inhibiting JAK activity, JAK inhibitors block cytokine signaling, reducing inflammatory responses and immune-mediated tissue damage.49 Studies have demonstrated their effectiveness in controlling symptoms and improving patients’ quality of life when used as an immunomodulator in combination with conventional treatments (e.g., 5-aminosalicylic acid, glucocorticoids, etc.) to achieve enhanced therapeutic outcomes. However, JAK inhibitors need to be used and monitored rationally in clinical applications due to potential adverse reactions and safety concerns.51

The mechanisms of immune homeostasis of JAK inhibitors in IBD treatment are not completely understood. Some studies have shown that JAK inhibitors can inhibit T lymphocyte activity, reduce the level of inflammatory factors, and reduce the infiltration of inflammatory cells.52 In addition, JAK inhibitors can affect the functions and differentiation of immune cells to regulate the balance of immune responses.

Others

Severalother BAs are available for IBD treatment, aiming to restore immune homeostasis by modulating the immune response.64

TGF-β1 is an archetypal cytokine with anti-inflammatory effects in diverse inflammatory diseases. Abnormal regulation of TGF-β1 is considered a critical link to the pathophysiology of IBD. Upon binding to its receptor, TGF-βRI is phosphorylated and activated, contributing to the phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules SMAD2 and SMAD3, which exertanti-inflammatory effects. However, SMAD7, a counter-regulatory member of the SMAD4 family, attenuates TGF-β1 signaling by binding to TGF-β1RI, imply ingreceptor degradation, and subsequently tackling the effects of SMAD2 and SMAD3. Consequently, the anti-inflammatory function of TGF-β1 is restrained.65

Other types of immune responses

Mucosal immune response

Defects in the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier are frequently observed in IBD.66 The intestinal epithelium plays an essential role in maintaining guthomeostasis, serving as a barrier between gut microorganisms and the host immune system. It is the first “gateway” to the body’s exposure to various environmental factors that can trigger disease activity.67

In intestinal epithelial cells, the TNF-α-TNFR2 signaling pathway increases the expression of myosin light chain kinase, which disrupts the assembly of tight junctions.68 Pro-inflammatory cytokines may further enhance epithelial leakage. Additionally, inflammation induces the so-called “cupping cell exhaustion”, which results in the inability to secrete normal mucins,69 and the dysregulation of IL7 cytokine secretion,whichprovokeschronic inflammation.70 Candidate risk sites for IBD, particularly the CARD15 mutation site encoding the bacterial sensing protein NOD2, have been associated with reduced alpha-defensin production (i.e., DEFA5 and DEFA6) in adult and pediatric patients with ileal CD.71,72 Therefore, defects in epithelial cell barrier function result inchronic exposure to bacterial molecules, causing the destructive intestinal inflammation characteristic of IBD.73

Humoral immunity

B-lymphocyte-mediated immune response

Humoral immunity is an asset in the development and progression of IBD. Under pathological conditions, abnormal functions of B lymphocytes may lead to changes in plasma cell numbers and activity, triggering autoimmune diseases that attack the body’s own tissues and produce an inflammatory response. Complex interaction sex is tbetween antibody formation and inflammatory mediators.74 BAs improve the condition of IBD patients by modulating the interaction between antibodies and inflammatory mediators. Antibody agents against TNF-αand IL12/23 have been developed for IBD treatment,75 but further research is needed to investigate the role of multiple immune responses.

Immune response of the complement system

The complement system consists of proteins that play a vital part in immune responses.76,77 The activated complement system participates in immune responses by directly killing microorganisms, facilitating phagocytic clearance, and eliciting an inflammatory response. When tissues are physically damaged, chemically stimulated, or infected, the body undergoes an inflammatory response, which is the body’s non-specific defense response to injurious stimuli,78 to remove the cause of the inflammation and restore the function of the damaged tissue.79

The intricate interplay between different immune response types and inflammatory mediators can be therapeutic for IBD. BAs are innovative in modulating these immune response types. By targeting specific subpopulations of immune cells, more precise regulation of immune homeostasis can be achieved.

Other immune reactions introduction

Cellular immunity

In IBD, increasing the number and/or function of Tregs can control inflammation and improve symptoms. Some therapies, such as anti-IL2 antibodies and anti-CTLA4 antibodies, have been proven to increase the number and function of Tregs, resulting in therapeutic effects on IBD.80 Other studies have explored increasing the number and function of Tregs through genetic engineering and cell therapy. For instance, one study used genetic engineering technology to introduce the IL10 gene into Tregs,81 increasing their number and function and successfully treating experimental colitis models. Additionally, another study cultured and expanded patients’ Tregs in vitro and then transfused them into the patient’s body to control inflammation and improve IBD symptoms.82

Cytokine-mediated immunity

Cytokines are proteins secreted by immune cells that play an essential regulatory role in immune responses.83 Cytokines can regulate the strength and type of immune response by acting on immune cells or other target cells, participating in the regulation of immune reactions and inflammatory processes. In IBD, the production and regulation of cytokines may be abnormal, leading to persistent and aggravated inflammation. Therefore, regulating cytokine production and activity can control inflammation and immune-mediated tissue damage, restoring immune balance.

Transforming TGF-β can inhibit the activation of immune cells and promote tissue repair. In IBD, the expression level of TGF-β may decrease, leading to persistent and aggravated inflammation. Increasing TGF-β expression or its biological activity can control inflammation and improve IBD symptoms.84 Similarly, IL10 can inhibit the activation of immune cells and the production of inflammatory mediators. In IBD, the expression level of IL10 may decrease, leading to exacerbated inflammation. Therefore, increasing IL10 expression or its biological activity can control inflammation and improve IBD symptoms.85

The immune responses mentioned in point 4 have been summarized in Table 2.86–90

Other types of immune responses involved in IBD

| Type of immune responses | Main mechanisms | |

|---|---|---|

| Mucosal immune response | TNF-α-TNFR2→myosin light-chain kinase(MLCK)↑→disrupting tight junctions; Pro-inflammatory cytokines→Enhancement of Epithelial Barrier Disruption; Inflammation→goblet cells↓→the inability to secrete normal mucus; Dysregulation of IL7 cytokine secretion→chronic inflammation86 | |

| Humoral immune response | Main components: B cells and antibodies; B cells→antigen receptor→Identify pathogen→Differentiation into plasma cells→Producing a large amount of antibodies87 | |

| Acquired immune response | Strong expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines→Performance: CD (Th1), UC (Th2)→Th17 cells change their activity88 | |

| Other types of immune response | Cellular immune response | Cell-mediated immunity→Direct interaction→An immune response against pathogens88 |

| Cytokines mediate immune response | Cytokines→Immune cells/other target cell→Regulating the intensity and type of immune response→Regulating immune responses and inflammatory processes89 | |

| Immune response of complement system | Activated complement system→Directly kills microorganisms, promoting phagocyte clearance, and causing inflammatory reactions→Participating in immune response90 | |

Conclusions and perspective

Maintaining the balance of Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg cells are vital immunological targets for BAs in IBD. The regulation mechanisms of these targets provide important strategies for reducing the non-response rates and the risk to patients from biological agents. In addition to the studied Th1/Th2andTh17/Treg balances, we could also focus on other balance, such as macrophages/natural killer (NK) cells, partly for that BAs can adjust the balance between macrophages and NK cells. Besides, BAs such as IFX can inhibit the TNF-α receptor on the macrophage surface, and ADL can inhibit TNF-α, thereby hindering macrophage activation and proliferation. Moreover, VDZ can inhibit CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as NK cells, while ustekinumab can stimulate the activation and proliferation of NK cells and promote the release of IFNγ, playing an anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor role.

Collectively, we hypothesize that future research directions of BAs in IBD could include explorations of the mechanisms and regulation methods of macrophage and NK cell balance. Itis possible that gene editing technology could be applied to adjust the balance of macrophages and NK cells to better control inflammation for IBD.

Declarations

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding

This article is funded by the High-Level Personnel Program of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (2021DFJH0008/KY012021458),theStarting Program fortheNational Natural Science Foundation of China at Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (8207034250),theNational Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 81300370),theNatural Science Foundation of Guangdong (NSFG, No. 2018A030313161), and by a General Program (No. 2017M622650) and a Special Support Program (No. 2018T110855) from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (CPSF).

Conflict of interest

Dr. Shixue Dai has been an Early Career Editor of Nature Cell and Science since June 2023. The authors have no other conflicts of interest related to this publication.

Authors’ contributions

Contributed to study concept and design (XY (Xuanyan), XY (Xiaowei Yan), SX, HW and SD), acquisition of the data (XY (Xuanyan), XY (Xiaowei Yan), SX and HW), assay performance and data analysis (XY (Xuanyan), XY (Xiaowei Yan), SX and HW), drafting of the manuscript (XY (Xuanyan), XY (Xiaowei Yan), SX, HW, YG and HT), critical revision of the manuscript (XY (Xuanyan), XY (Xiaowei Yan), SX, HW, YG and HT), supervision (SD).

Author information

Author information